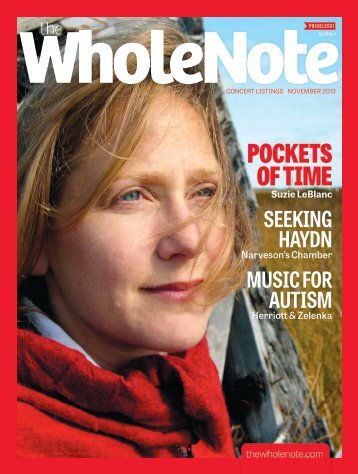

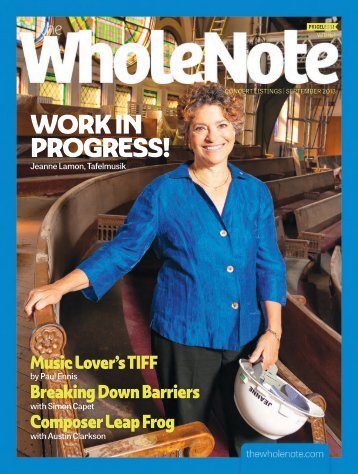

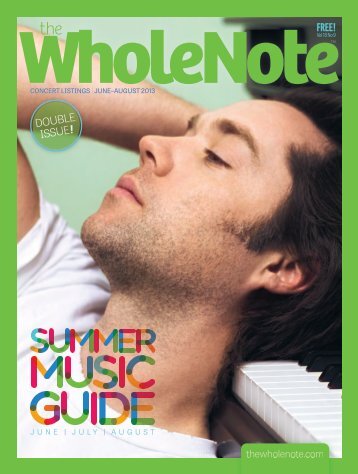

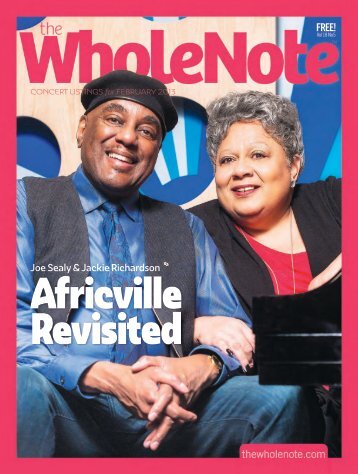

Volume 17 Issue 9 - June 2012

- Text

- Jazz

- Toronto

- Festival

- Concerts

- August

- Musical

- Theatre

- Arts

- Festivals

- Symphony

MUSICAL FRAMEWORKS: AN

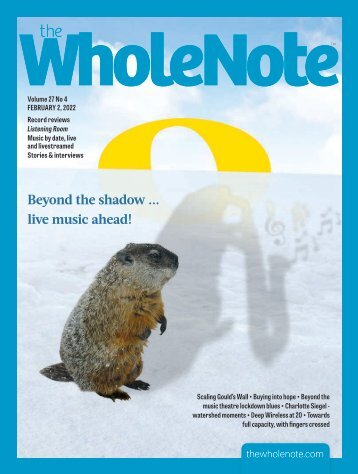

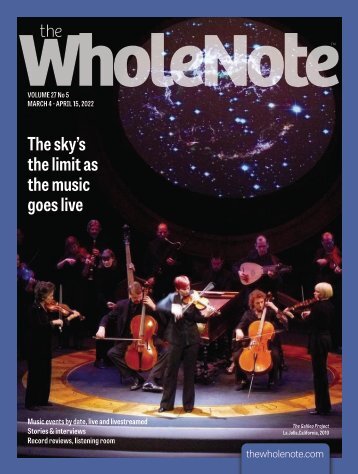

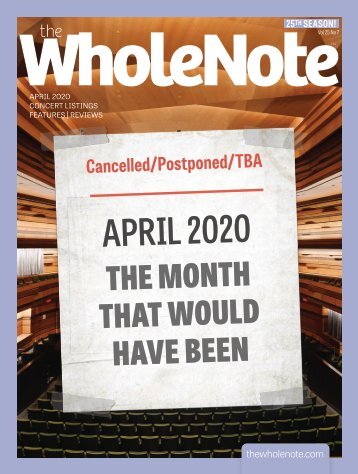

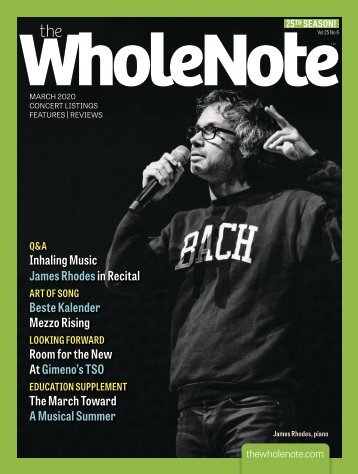

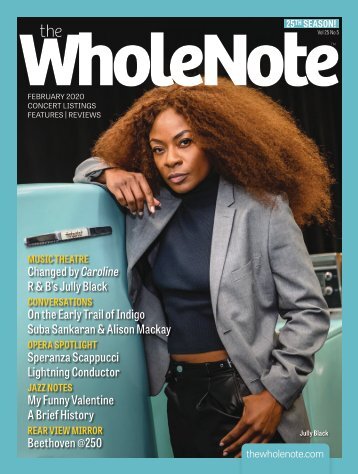

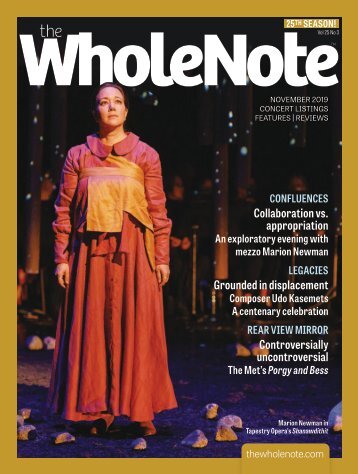

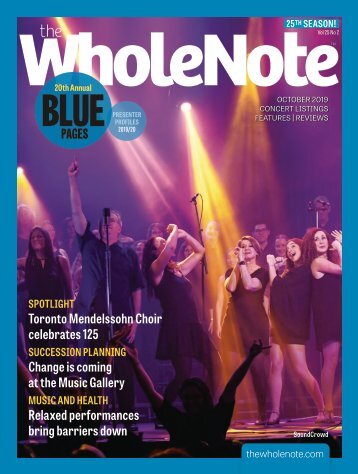

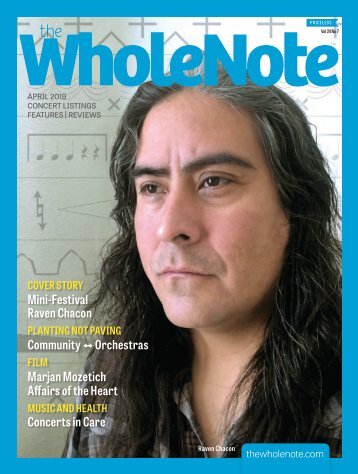

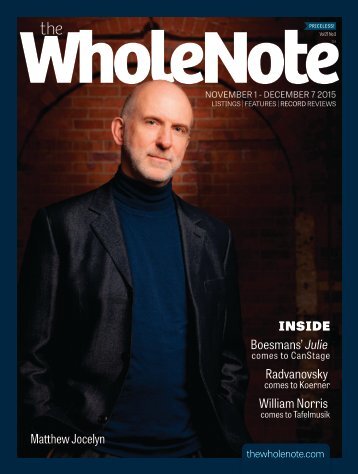

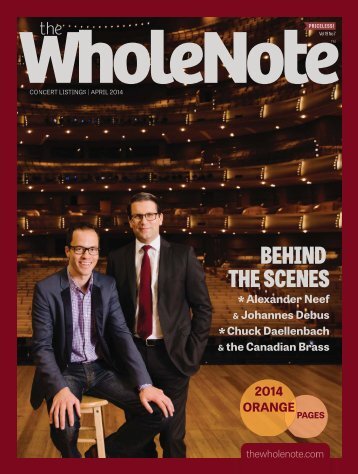

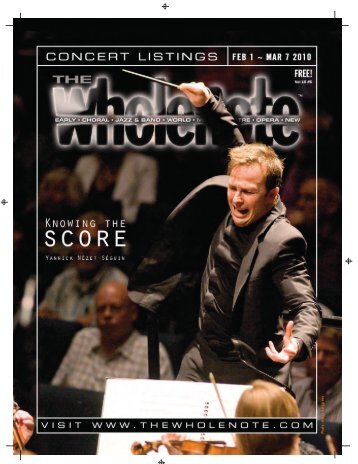

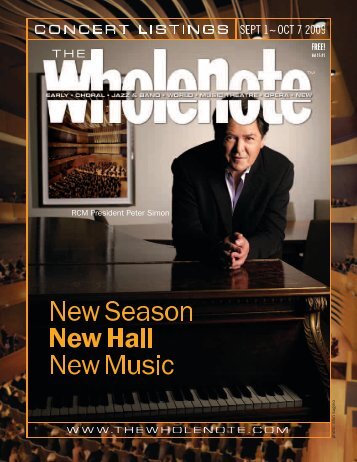

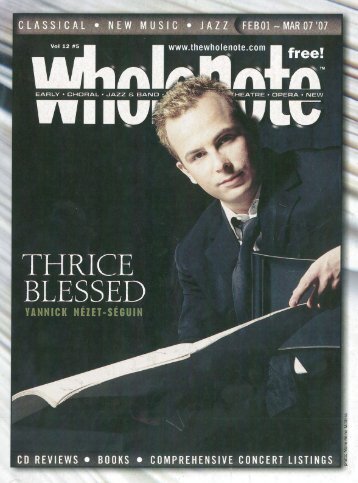

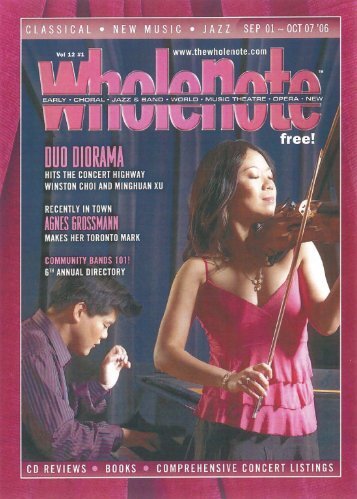

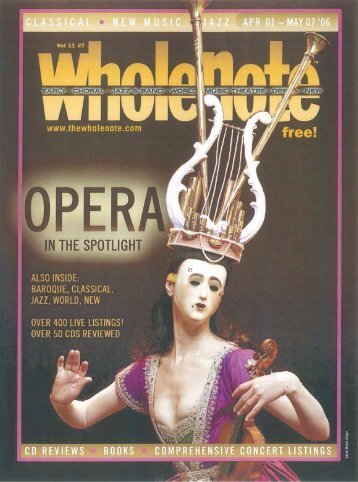

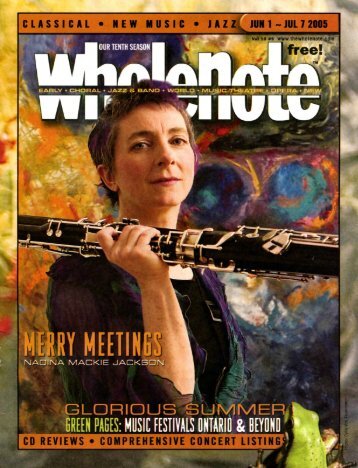

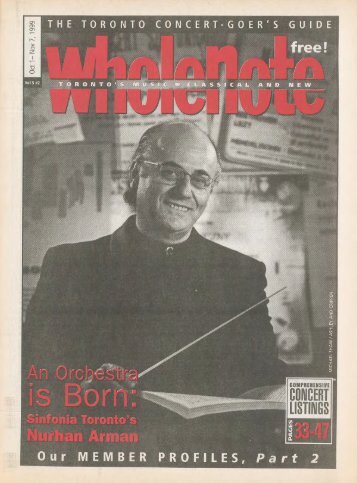

MUSICAL FRAMEWORKS: AN INTERVIEW WITH JACK DIAMONDI noticed that the orchestra sits on risers in your new hall for theMontreal Symphony — was that your decision?Of course.Do you think the risers improvethe sound?No question.The first rule ofacoustics is thatif you can see wellyou can begin to hearwell. You hear withyour eyes and yousee with your ears.So seeing is good. Butrisers don’t only givevisibility. There’s alsoan acoustic reasonfor them — in my viewthere’s always an acousticbasis that shoulddrive design. So I like toput the timpani and brasson risers because I thinkit helps dampen the soundslightly. Then when you putthe strings on a hard surfacein front, you get morereflectivity. So that hallis particularly responsiveto strings.Do you think if the Toronto Symphony sat on risers it would improvethe sound in Roy Thomson Hall?No question.After hearing the Montreal Symphony in their new hall, I couldn’t helpwishing we had a symphony hall in Toronto which sounds like that one.You can draw your own conclusions about this, but when an architectwith a romantic view about architecture chooses an arbitraryshape as an artist and then says to the acoustician, “Fix it!”, the bestyou can get is six out of ten —the best. If, however, the architect workswith an acoustician and starts out with the physics of sound, so thatthe shape of the hall is a derivative, you get an eight or nine. You canthen tune the hall by moving curtains and so on, though I don’t believein too many moving parts —I think you should design a hall, period.As good an architect as Arthur Erikson [the architect of Roy ThomsonHall] was, his personal talent got in his way. For me it’s not only moresatisfying to be driven by necessity, but it’s ultimately more gratifying.You create a more sustainable design if you are driven by necessity.Like good sound?That’s one, but there are others. I believe that the true secret of designis making virtues of these necessities. Take them and celebrate them.I like your word “celebrate.”I really like to celebrate the needs, the technology. And then, in theend, if you make the form out of the demands of sound, and the decorationout of the technology itself, you get a design that you couldn’thave thought of on your own.So the proverbial sketch on a napkin doesn’t take you very far?You know what the problems with all those are —they are just sketcheson napkins. You should wipe your mouth after the meal and throwthe napkin away. There’s a wonderful short-hand in a drawing, butthe conception should be based upon knowledge of the technology.Then you find a clever way of improving the conception. When you’vegot limited means and a real demand, that’s how innovation comesabout. You can’t intuit a complex problem if you have no knowledgeof it. So you must first figure out the issues involving the physical demands,such as sound attenuation.In the Toronto opera house, the hall is a separate piece that doesn’ttouch the outside. Aesthetically you get an egg sitting very gently inits nest. The inside is curvilinear, the outside rectilinear. No soundaudible to the human ear penetrates it. The reason that’s importantis that the quieter the room, themore audiences can appreciate thenuances of the sounds generatingthe music. That whole building ison rubber pads, and it has huge,heavy walls and beams that stopboth airborne and structuralbornesounds. How could youdo that with a little scribbleon a napkin? Those principlesshape the design. So that’s whatI mean by necessity.You were put through thewringer during the planningstages of the opera house bysome — not primarily operalovers,I think — who wanteda landmark signaturebuilding by someone likeFrank Gehry.He’s a talented guy.But I imagine you thinking,who do they think IMaison Symphonique de Montréal.am, a nobody?Exactly.“When an architect with a romantic viewabout architecture chooses an arbitrary shapeas an artist and then says to the acoustician,‘Fix it!’, the best you can get is six out of ten.”I recall that Bradshaw was always adamant in his support foryour design.And his people who had been working with me said, “No way.” Ihave great admiration for Gehry. He has a plastic talent that’s brilliant.The problem is that it’s idiosyncratic. You can’t develop a schoolout of that, so the works of his disciples, like the new art gallery inEdmonton, are not as good as his. Everybody else who tries to followthat principle is a second class Gehry, because it’s artistic.Do you consider your work equally artistic, only that you are startingfrom the inside out?I hope so, but what drives the aesthetics —its structure and foundation—is a rational base. It’s much more satisfying aesthetically thanstarting from an arbitrary base, where I make any shape that I choose.For me that doesn’t have authenticity, because it’s arbitrary.While the opera house was being built, Bradshaw always talkedabout the sound and the sightlines, rather than how striking andbeautiful it would look.That’s right. No question, he knew what the issues were, and I agreedwith him absolutely. Those are the fundamentals, otherwise it’s not agood opera house. It’s like the Sydney Opera House —it’s a great symbolfor Sydney, but it’s a lousy opera house. The architect chose shapeswhich are intriguing and beautiful, and it’s a lovely piece of sculpture.But it’s not delivering a great opera house. So what’s the purpose ofthat building? Its iconic and symbolic aspects, with its location onSydney harbour, are very important, but they should not be at theexpense of its primary purpose, which is an opera house. My point isthat a beautiful building and a workable building should not be mutuallyexclusive.In fact, this architectural practice that we have here is based uponthe resolution of those two —perhaps not a resolution, since that soundslike they are in conflict. It’s that one informs the other. The functionis all-important, and it’s expressed in a way that is wonderful. To methat’s the essence of great architecture. Whether it’s Gothic architectureor Greek architecture, it’s really that it works, that its technologyis inherently authentic.continued on page 70TOM ARBAN10 thewholenote.com June 1 – July 7, 2012

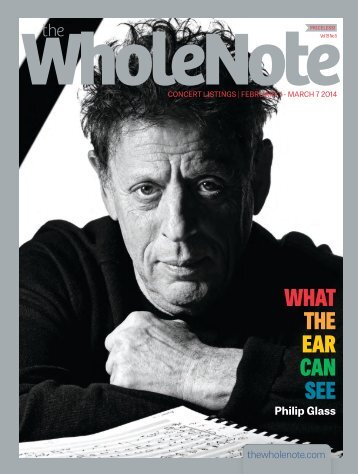

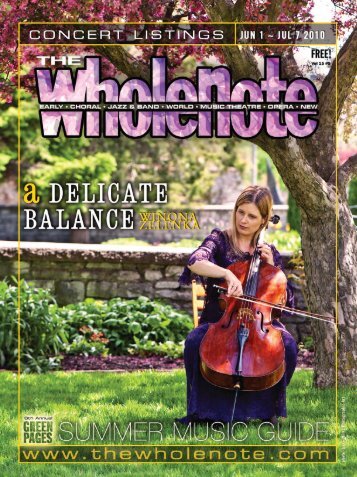

Beat by Beat | On OperaCollaboratorsRobert Wilsonand PhilipGlass.Music at Sharon“Where souls come to listen in harmony”– Sir Mckenzie King, Prime MinisterLarry Beckwith and Rick Phillips, Artistic DirectorsSponsorship OpportunityFour Sunday Help afternoons celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Sharon of Temple. glorious musicwww.musicatsharon.cain a magical and acoustically stunning settingIconic EinsteinJune3schubert’s WinterreiseDaniel Lichti, bass-baritonePentaèdre Wind EnsembleJoseph Petric, accordionFranz Schubert’s captivating song cycleas you’ve never heard it before, sung bydistinguished bass-baritone Daniel Lichti.Lucie janSCHChristopher HoileThe operatic highlight of the year arrives this June as part ofLuminato. It’s the Canadian premiere of Philip Glass’ iconoclastic1976 opera Einstein on the Beach in its first new production in20 years. The New York-based organization Pomegranate Arts premieredthe new production in Montpellier, France, with the expresspurpose of touring it to places where it had never before been seen.As a seminal creation that redefined what opera is, it is the one workthis year that no lover of modern opera can afford to miss.Einstein on the Beach resulted from the collaboration of composerPhilip Glass, director Robert Wilson and choreographer LucindaChilds. The notion was to create a plotless, image-driven, multimediaexploration of the world-changing ideas of one great man. Thetitle itself combines the name of the subject with the title of NevilShute’s 1957 novel On the Beach, about the end of life on earth due toa nuclear holocaust.Einstein on the Beach breaks all of the rules of conventional opera,including the relationship among the work’s creators. Robert Wilsondid not write a traditional libretto but rather created a series of storyboardssuggesting structure and designs that inspired Glass’ music.Non-narrative in form, the work uses the development of powerfulrecurrent images as its main storytelling device in juxtapositionwith abstract dance sequences created by Lucinda Childs.Einstein on the Beach is structured in four acts connected by fivedanced “knee plays.” The four acts of the opera –Train, Trial 1 & 2and Field/Spaceship —refer to Einstein’s theories of relativity and hishypothesis of unified field theory, with the “Trials” focussed on themisuse of science as implied in the second half of the title. Instead ofa traditional orchestral arrangement, Glass composed the work forhis own amplified ensemble consisting of three reed players —flute(doubling piccolo and bass clarinet), soprano saxophone (doublingflute), tenor saxophone (doubling alto saxophone); solo violin (playedby the non-singing character Einstein on stage) and two synthesizers/electronicorgans. The cast requires two females, one adult maleand one male child in speaking roles with a 16-member chorus withone male and female soloist. Because of its nearly five-hour length,there are no traditional intervals. Instead, the audience is invited toenter and exit at liberty during the performance.Einstein on the Beach was Glass’ first opera and the first collaborationbetween Glass and Wilson. For the new production, they areworking with a number of their long-time collaborators, includingJune10June17dido & aeneasMeredith Hall as DidoTodd Delaney as AeneasToronto Masque TheatreLarry Beckwith, DirectorDido and Aeneas, the powerful operaticmasterpiece by Henry Purcell, sung by a groupof brilliant singers including the luminoussoprano Meredith Hall and charismatic youngbaritone Todd Delaney in the title roles.June24ZelenKa Plays bachWinona Zelenka, celloThree of the profoundly movingsolo cello suites by JohannSebastian Bach, played by Winona Zelenka,one of the leading cellists of our time.Kradjian Plays debussySerouj Kradjian, pianoA wide-ranging piano recitalfeaturing the music of ClaudeDebussy, in commemoration of the 150thanniversary of his birth, played by the“keyboard acrobat” Armenian-Canadianpianist, Serouj Kradjian.For all dates: Pre-concert chat at 1:15 p.m.,followed by 2 p.m. concertGet your tickets today!www.musicatsharon.ca905-830-4529Sharon Temple National Historic Site and Museum18974 Leslie Street, Sharon, Ontario(just north of Newmarket, Ontario)June 1 – July 7, 2012thewholenote.com 11

- Page 1 and 2: Vol 17 No 9CONCERT LISTINGS | JUNE

- Page 3 and 4: 416.593.4828tso.caSchumann& Shostak

- Page 5 and 6: Volume 17 No 9 | June 1 - July 7, 2

- Page 7 and 8: THE ALDEBURGH CONNECTIONpresents th

- Page 9: MICHael COOPer; DIAMOnd SCHmiTT ARC

- Page 13 and 14: Beat by Beat | Early MusicOut of th

- Page 15 and 16: Beat by Beat | Classical & BeyondGo

- Page 17 and 18: elease puts it. She’s the only vi

- Page 19 and 20: aforementioned Brian Current) Frida

- Page 21 and 22: Courtesy of LuminaTOThe father of s

- Page 23 and 24: Here are details for some other eve

- Page 25 and 26: Beat by Beat | Music TheatreStratfo

- Page 27 and 28: Midland is a Jazz Party. The First

- Page 29 and 30: drop around and have a look at the

- Page 31 and 32: Agincourt. 416-491-1224. . All p

- Page 33 and 34: • 7:30: Wellness Path. GuruGanesh

- Page 35 and 36: piano. 2118-A Bloor St. W. 416-621-

- Page 38 and 39: See June 1.• 2:00: Stratford Shak

- Page 40 and 41: Beat by Beat | In the ClubsC. In th

- Page 42 and 43: shows). Jun 28 8pm Laura Fernandez;

- Page 44 and 45: GALAS & FUNDRAISERS• Jun 16 8:00:

- Page 46 and 47: Classified Advertising | classad@th

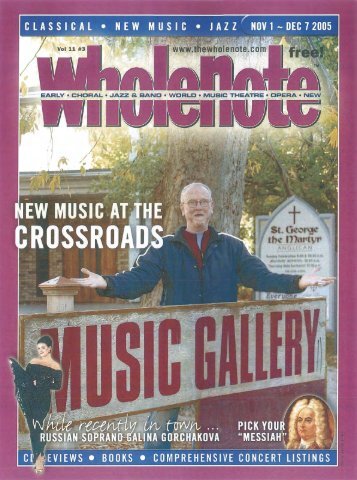

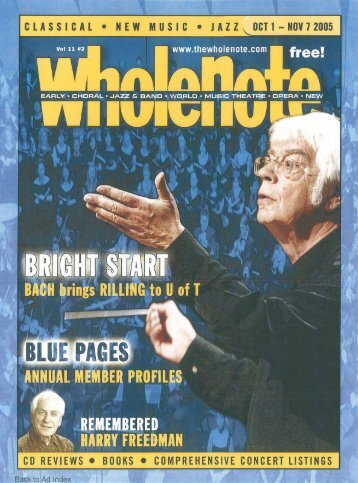

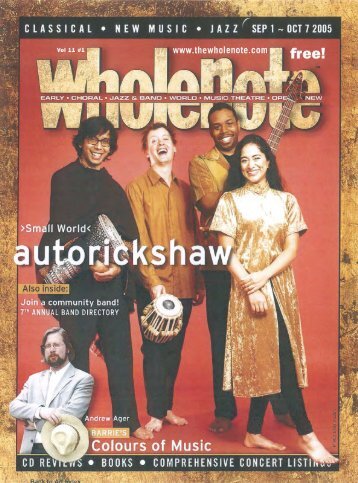

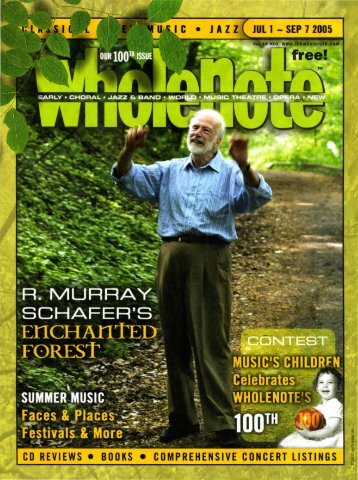

- Page 48 and 49: WE ARE ALL MusIC’S CHILDRENJune

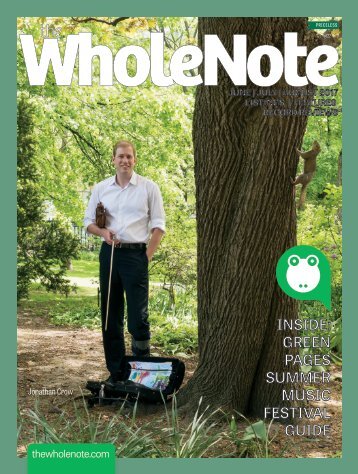

- Page 50 and 51: Green Pages 2012theWholeNote 2012 S

- Page 52 and 53: Green Pages 2012theWholeNote 2012 S

- Page 54 and 55: theWholeNote 2012 SUMMER MUSIC GUID

- Page 56 and 57: theWholeNote 2012 SUMMER MUSIC GUID

- Page 58 and 59: FESTIVAL DIGEST!!Jewish Music Week

- Page 60 and 61:

DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS REVIEWEDEd

- Page 62 and 63:

ers who reveal whythat neglect cann

- Page 64 and 65:

three Bach Concertos on her latest

- Page 66 and 67:

and Düsseldorf. It is a schizophre

- Page 68 and 69:

2009, becoming asignificant membero

- Page 70 and 71:

MUSICAL FRAMEWORKS: AN INTERVIEW WI

- Page 72:

The Great Escape“A Midsummer Nigh

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...