Volume 20 Issue 1 - September 2014

- Text

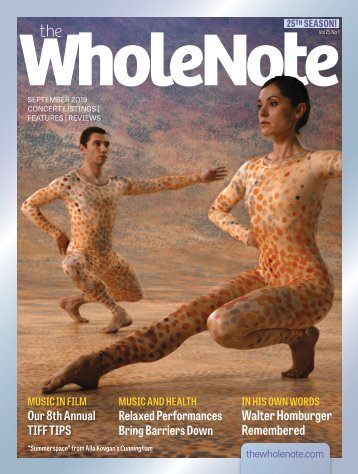

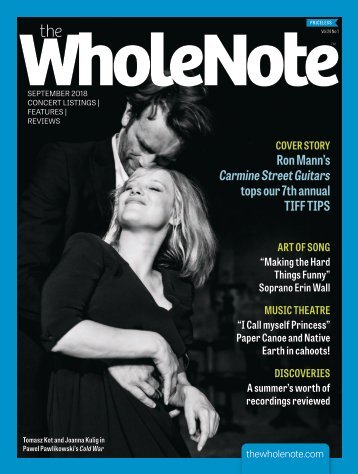

- September

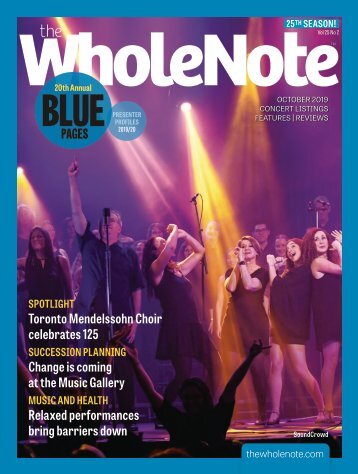

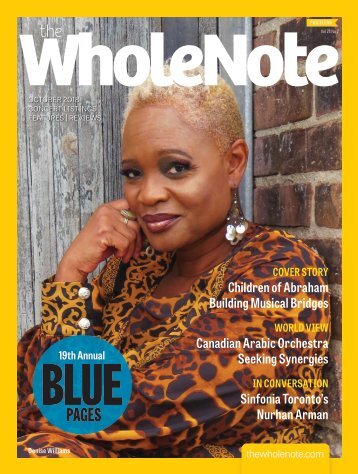

- October

- Toronto

- Jazz

- Musical

- Theatre

- Festival

- Concerts

- Symphony

- Arts

DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS

DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS REVIEWEDWhat I Did On My Summer VacationDAVID OLDSIt all began as I was registering for an online service and was asked the security question “Who is your favourite author?” I realized that theanswer has not changed in about 35 years since I first read William Gaddis’ The Recognitions (I hope this admission will not leave me vulnerableto identity theft!) which led to a re-reading of his final work, Agapē Agape. And there my story begins...With Gaddis’ fixation on mechanicalreproduction (specifically the invention ofthe player piano) and the ways technologychanged the perception and availability ofart in the 20th century, in particular thephenomenon of Glenn Gould and Gould’swish to “eliminate the middleman andbecome [one with] the Steinway,” the stagewas set for my wonderful summer’s journey.It began with The Loser, Thomas Bernhard’saccount of a fictional Glenn Gould’s studiesin Salzburg with Vladimir Horowitz, and thedevastating effects his presence (and his interpretationof the Goldberg Variations) had ontwo fellow students, the unnamed narratorand the character Wertheimer, who abandonedpromising solo careers and were ultimatelydestroyed by the contact (Wertheimer infact a suicide). Evidently Gaddis was readingBernhard toward the end of his life and it wasthere he found the premise of Gould wantingto become the piano.It was about this timethat I realized that abook which had arrivedat The WholeNote afew months earlier andwhich I had browsedbut put down as beingtoo dry and academic,The Musical Novelby Emily Petermann(Camden House 978-1-57113-592-6), mightprovide some insightsand inspiration after all.I still found it hard going – with its use ofsuch unfamiliar words as inter-, intra- andmulti-medial, poiesis and palimsestuous (asopposed to palimsestic, she explains), allof which I was able to make out from theirroots and context but which I notice set offspell-check alarms – and ended up focussingon Chapter 5: “Structural Patterns inNovels Based on the Goldberg Variations.” Ofthe four books analyzed – Gabriel Josipovici’sGoldberg: Variations; Nancy Huston’sThe Goldberg Variations; Rachel Cusk’sBradshaw Variations and Richard Powers’Gold Bug Variations – I had read (severaltimes) all but the Cusk. The inclusion of thislatter was in itself worth the effort of perseveringwith Petermann’s thesis.I took a break from the scholarly tometo (re)read each of the books in question.Reading them all together, interspersed with anumber of recordings of the namesake, occupiedme for most of a month and providedsome delightful moments and revelations.Having now gone back to The Musical Novelto read Chapter 6 and the Conclusion hasalso furnished a number of explanations andclarifications, both about the novels in questionand the structure of Bach’s masterpiece.An example of the former is Cusk’s inclusionof a narrator-less chapter writtenentirely in dialogue without commentary(shades of Gaddis, although Cusk’s speakersare identified) which stuck in the craw ofat least one reviewer as being non-sequiturialand annoying for its lack of context.Petermann points out that the chapter inquestion is parallel to Bach’s Variation XXVIIin the structure of the book and is a literaryrepresentation of this “canon at the ninth,”which involves just two voices without the“commentary” of the bass line present in allof the other variations. So there is the contextwhich the reviewer found lacking. LikewisePetermann explores the unique A-B structureof Variation XVI, the midpoint of Bach’s cycle,and relates it to several of the literary works,most notably the Josipovici. In an extension ofthe legend of the origin of another of Bach’smasterpieces, The Musical Offering, Josipovicirecasts the story of Bach’s musical meetingwith Frederick the Great to be Goldberg’s –a writer rather than a harpsichordist in thisnovel – literary joust with King George III andsubsequent reworking of the King’s themeinto “seven tiny tales” and a longer three-partcautionary story. Other insights abound…Bach provided the title Clavierübung(keyboard study) consisting of an Aria withDiverse Variations for the Harpsichord withTwo Manuals Composed for Music Lovers,to Refresh their Spirits. Johann NikolausForkel, in the first biography of Bach writtensome six decades after the composer’s death,provided a background story from which thename we now associate with the work originated.Forkel tells us that Baron von Keiserling,an insomniac who employed a young harpsichordplayer named Goldberg to play himsoothing and entertaining music at nightfrom an adjoining room to help him sleep, orat least deal with his sleeplessness, commissionedBach to write a set of suitable piecesfor Goldberg to play. That story has long sincebeen debunked, as listening to some of themore rambunctious variations might suggest,but the myth has continued to entice us formore than two centuries.The recordings Irevisited duringthis extensiveimmersionin the GoldbergVariations wereof course GlennGould’s seminal 1955and ultimate 1981versions (in a 2002three-CD commemorativepackage that includesan extended conversation between Gouldand music critic Tim Page, SONY S3K 87703),plus Luc Beauséjour’s harpsichord rendition(Analekta fleur de lys FL 2 3132), DmitriSitkovetsky’s string trio arrangement withSitkovetsky, Gérard Causé and Misha Maisky(Orfeo C 138 851 A, but you might choosea Canadian recording of the same arrangementwith Jonathan Crow, Douglas McNabneyand Matt Haimowitz on Oxingale OX2014,reviewed by Terry Robbins in the March 2009WholeNote) and Bernard Labadie’s stringorchestra version with Les Violons du Roy(Dorian xCD-90281), each of which bringsvery different aspects of the work to light andall of which I would recommend withouthesitation. As I would the literary titlesmentioned above.It was a newrecording, BachGoldberg Variationsfor Two Pianos,that drew myparticular attentionhowever. EvidentlyJoseph Rheinberger(1839-1901)felt that the original 1741 solo keyboard(two-manual harpsichord) work wouldprovide enough material to keep two pianistsbusy and in 1883 made an arrangementfor two pianos in which the liner notestell us he “took substantial liberties withBach’s original voicing, doubling melodiesand fleshing out harmonies as he saw fit…[leaving] an unmistakably Romantic impressionon the work.” Thirty years later MaxReger “smoothed out a few of the [remaining]rough edges” of Rheinberger’s adaptationand published the version recorded here in awonderful performance by Nina Schumannand Luis Magalhães (TwoPianists RecordsTP1039213). It is this “Romantic” version for66 | September 1, 2014 – October 7, 2014 thewholenote.com

two pianos that comes the closest to beingsomething I would like to hear at the edgeof sleep. If I ever have the luxury of going tobed next to a room furnished with two grandpianos and such accomplished performers asSchumann and Magalhães I would love to putthe Keiserling premise to the test.Having spent July immersed in Bach’smusic, I spent August exploring the firsthalf of Petermann’s treatise, devoted to theJazz Novel, a genre with which I am mostlyunfamiliar. As a matter of fact MichaelOndaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter is theonly book covered that I had read, and ToniMorrison the only other author mentioned Ihad previously heard of. It turned out to bequite a challenge to track down many of thebooks discussed, but I am pleased to say that,after a mostly unfruitful search at the TorontoPublic Library, with the aid of Toronto’s (fewremaining) used book sellers and the InternetI have been able to find books by all of theauthors discussed (including Xam WilsonCartier, Christian Gailly, Jack Fuller, StanleyCrouch and Albert Murray). This too has beena very satisfying journey.You might think that after all thoseGoldberg Variations I would have hadenough of Bach for a while, but perhapsI am like those animals who, even whenchoices abound, continue eating a single foodtype until its source is depleted before movingon to something else (not that one could everexhaust the available wealth of Bach recordings).For a changeof pace I found thata new recording ofBach Cantatas entitledRecreation for theSoul featuring theMagdalena Consort(Channel ClassicsCCS SA 35214) didindeed provide a refreshing respite. I mustconfess that I am not well versed in Bach’smany cantatas – some 209 have survived –although I am of course familiar with some ofthe more famous arias. Listening to this newrecording, which features stellar soloists PeterHarvey (bass and direction), Elin ManahanThomas (soprano), Daniel Taylor (alto) andJames Gilchrist (tenor) in one-voice-per-partarrangements, I was pleasantly surprised tofind that the beloved melody I know as Jesu,Joy of Man’s Desiring appears not once buttwice in the cantata Herz und Mund und Tatund Leben (Heart and mouth and deed andlife) BWV147, as the final chorale of Part OneWohl mir, dass ich Jesum habe (What joy forme that I have Jesus), and as the grand finaleof the work, Jesus bleibet meine Freude (Jesusremains my joy). The other “musical offerings”on this marvelous disc are Jesu, der duMeine Seele (Jesu, by whom my soul) BWV78and Nach dir, Herr, Verlanget Mich (Lord, Ilong for you) BWV150, both rich in Bach’strademark melodies and counterpoint, heardhere in a clarity not always found in fullchoral presentations. Highly recommended.Hoping to wean myself gently off the Bachoverdose and realizing that no one writing forsolo cello would be able to avoid at least someinfluence of themaster, I decided tocheck out Lady inthe East, Solo CelloSuites 1-3 by BCcomposer StephenBrown, featuringHannah Addario-Berry (stephenbrown.ca).The opening notes of TakakkawFalls, Suite No.1 confirmed my suspicionregarding echoes of Bach, but almost immediatelythe contemplative Air established itsown independent voice and the followingStrathspay & Reel and Slow Waltz, althoughbased on dance patterns like a Baroque suite,were obviously drawing inspiration fromdifferent cultural sources – Canadian folksongs and fiddle tunes. It is not until halfwaythrough the final Jig that we once again finda nod to Bach in a stately middle passagebefore a return to the playful fiddle tune ofthe opening.I find it interesting to note that the suitewas originally composed for solo flute. In mycorrespondence with Hans de Groot aboutthe disc of Francis Colpron’s transcriptionsfor recorder reviewed elsewhere in thesepages I mentioned that one of my favouriteversions of the Bach cello suites was MarionVerbruggen’s performance on the recorder.I’m pleased to note that the process of translationcan also work the other way around,from flute to cello.The disc includes two other suites(evidently Brown has composed six in all, sofar), Fire, which is influenced by the classicrock of Hendrix, Procol Harum, Cream andthe like, adapted very effectively and idiomaticallyfor solo cello, with a contrastingslow Recitative and Aria movement againreminiscent of Bach, and There Was a Ladyin the East in which Brown returns to folksongs and fiddle tunes. As an amateur cellistI am pleased to note that the sheet music forthese works is available from the CanadianMusic Centre (musiccentre.ca). I availedmyself of the CMC’s purchase-and-print-ityourselfservice and have enjoyed the challengeof working on the first suite in the pastfew weeks.My final selection this month does notshow any noticeable influence of J.S. Bach,but does feature solocello with German-Japanese DanjuloIshizaka accompaniedby pianistShai Wosner. Grieg,Janáček, Kodály(Onyx 4120) featuresthree relativelyobscure, or at least rarely recorded, works forcello and piano – Janáček’s dark and lyricalPohádka (Fairy Tale) and his brief, dramaticPresto, whose origin is unclear but whichmay have been meant originally as a movementof the fairy tale suite, and Grieg’sCello Sonata in A minor, Op.36. Ishizaka’scommitted performance of the Grieg andJanáček works makes me wonder why theyaren’t more often played. After all, these aremature works by respected composers whodid not publish much in the way of chambermusic – in the case of Grieg two violin sonatasand a string quartet and Janáček just a smatteringof works for violin and piano, twostring quartets and a woodwind sextet. Thatalone would make this recording important,but for me it is the centrepiece of the disc,a staple of the modern repertoire, Kodály’sSolo Cello Sonata Op.8 which is mostworthy of note.Presented in a context of “folkloric” worksin the liner essay by Ishizaka, I find it hardto make that connection. Of course Kodályworked with Bartók in the early yearsof the 20th century collecting and transcribingliterally thousands of folk songs fromHungary and surrounding lands, and thisexperience had a lasting influence on bothcomposers and their music. But frankly Idon’t hear it here. From the abrasive openingthrough a contemplative middle movementand on to its driving finale, this extendedwork from 1915 is a thoroughly modern,uncompromising tour de force which extendsthe cello’s sonic possibilities with its re-tunedand simultaneously plucked and bowedstrings. Ishizaka’s performance brings out allthis and more. It’s a welcome addition to thediscography.I mentioned above that I imagined that allcomposers writing for solo cello would beinfluenced by Bach’s solo suites. I find myselfunable to find these influences in Kodályhowever, although I have come up with anexplanation. It was Pablo Casals who firstbrought widespread attention to the Bachsuites, having stumbled upon the score in1890 at the age of 13. He then proceededto spend several decades working on thesuites and developing them as the performanceshowpieces we know today. Before thattime it seems they were regarded as merefinger exercises, learning pieces not fit for theconcert hall. Although Casals did record fourof the six movements of the C Major Suite in1915, the year Kodály composed his Sonata, itwould be two more decades before he madehis seminal recordings of the entire cycle.I think it may well be that Kodály was notaware of the Bach Suites when he composedhis masterwork. If this is indeed the case, it isan even more remarkable achievement.We welcome your feedback and invitesubmissions. CDs and comments should besent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., TheCentre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 BathurstSt. Toronto ON M5S 2R4. We also encourage youto visit our website where you can find addedfeatures including direct links to performers,composers and record labels, and additional,expanded and archival reviews.David Olds, DISCoveries Editordiscoveries@thewholenote.comthewholenote.com September 1, 2014 – October 7, 2014 | 67

- Page 1 and 2:

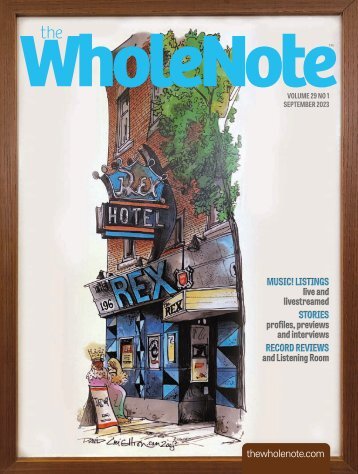

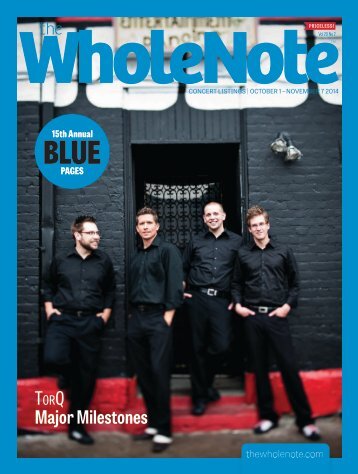

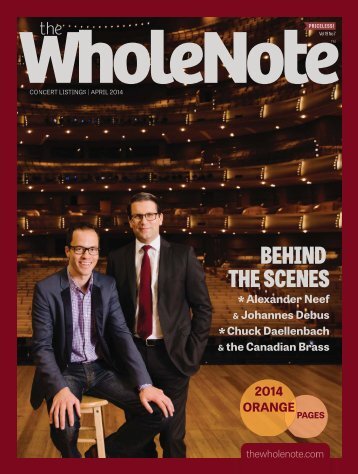

PRICELESS!Vol 20 No 1CONCERT LISTIN

- Page 3:

TORONTO INTERNATIONALPiano Competit

- Page 6 and 7:

FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMANThere’

- Page 8 and 9:

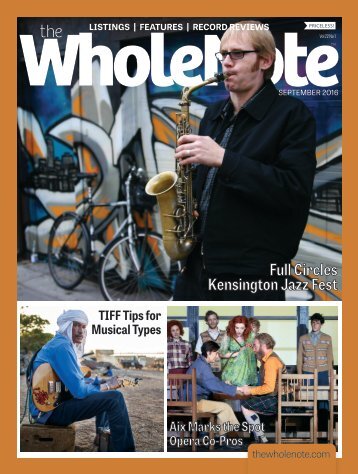

TIFF TIPSBY PAUL ENNISWelcome to Th

- Page 10 and 11:

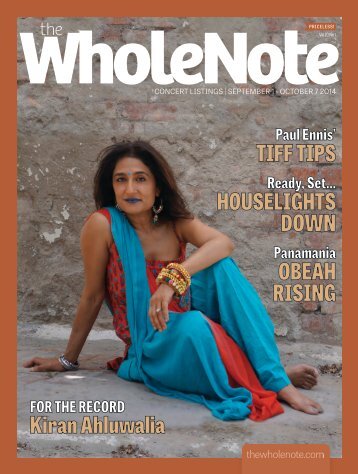

For The RecordKiran AhluwaliaANDREW

- Page 12 and 13:

Ready, Set...Houselights DownSARA C

- Page 14 and 15:

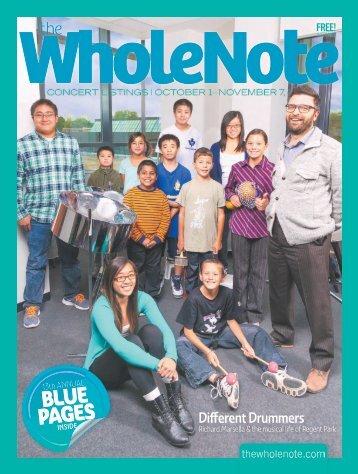

them, and then I facilitate theirwo

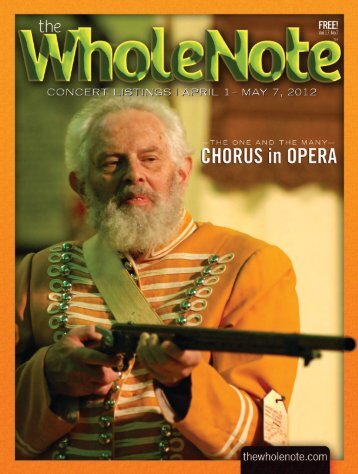

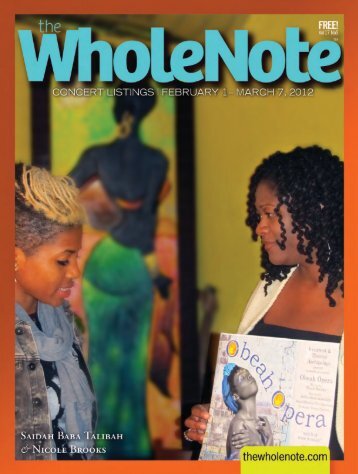

- Page 16 and 17: SARAH BAUMANNPanamania-Bound: Obeah

- Page 18 and 19: MIGUEL-DIETRICHBeat by Beat | World

- Page 20 and 21: Beat by Beat | Classical & BeyondCo

- Page 22 and 23: Glionna MansellPresents14A Music Se

- Page 24 and 25: days later Fewer and the other memb

- Page 26 and 27: ALEXANDRA GUERSONA republic of rich

- Page 28 and 29: space has enabled. One of the major

- Page 30 and 31: Beat by Beat | Art of SongRecitals:

- Page 32 and 33: KATIE CROSS PHOTOGRAPHYAnd beyond t

- Page 34 and 35: music specialist Michael Hofstetter

- Page 36 and 37: Beat by Beat | Choral SceneChoral S

- Page 38 and 39: an Ontario government agencyun orga

- Page 40 and 41: Beat by Beat | BandstandWell Tattoo

- Page 42 and 43: The WholeNote listings are arranged

- Page 44 and 45: ●●7:30: Westwood Concerts. Fair

- Page 46 and 47: Free, donations welcome.●●12:10

- Page 48 and 49: Marques, drums; Michael Shand, pian

- Page 50 and 51: (The Journey). Schubert: Der Hirt a

- Page 52 and 53: B. Concerts Beyond the GTA Beat by

- Page 54 and 55: SAXEBeat by Beat | In the Clubs (co

- Page 56 and 57: Of White Nights and Shapeshifting G

- Page 58 and 59: awareness, accessibility, participa

- Page 60 and 61: MUSICAL LIFE: CONCERT DO’S AND DO

- Page 62 and 63: Dis-Concerting continued from page

- Page 64 and 65: SEEING ORANGEdrive me home, stoppin

- Page 68 and 69: VOCALAlma & Gustav Mahler - LiederK

- Page 70 and 71: his playing.“The Harmonious Black

- Page 72 and 73: essential recording of this reperto

- Page 74 and 75: Eclectic and artful, Whose Shadow?

- Page 76 and 77: own and other orchestras, there is

- Page 78 and 79: Tiff Tips continued from pg 9Timbuk

- Page 80: MADAMABUTTERFLYPUCCINIOctober 10 -

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...