Volume 20 Issue 1 - September 2014

- Text

- September

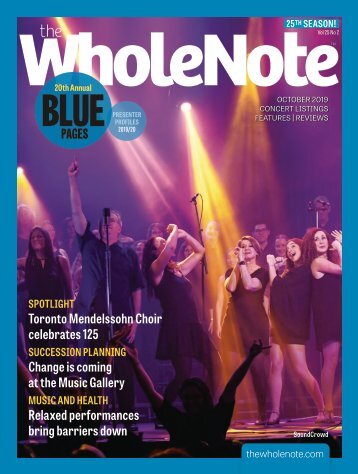

- October

- Toronto

- Jazz

- Musical

- Theatre

- Festival

- Concerts

- Symphony

- Arts

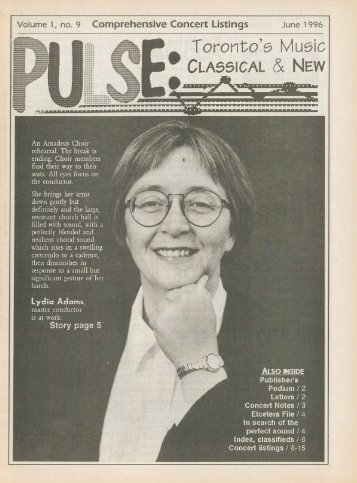

his playing.“The

his playing.“The Harmonious Blacksmith” is a hard actto follow. Both Driver’s and Egarr’s renditionsof the Suite 6 gigue are dashing, in contrastwith the largo in the same suite. It is easy tosay that the remaining suites comprise thedance-based movements already discussed,but Suite 7 concludes with a passacaille:chaconne. With Egarr’s combination of stridentand exuberant playing, perhaps thismovement is the sole differentiation betweenpiano and harpsichord.And on a personal note, Driver’s sleevenotes refer to frescoed ceilings by Bellucci.They are still there in the local Church ofSt. Lawrence: this reviewer grew up a halfmile from them.Michael SchwartzCLASSICAL AND BEYONDThe Classical Piano Concerto Vol.1 – DussekHoward Shelley; Ulster OrchestraHyperion CDA68027Was it really 23 years ago that Hyperionissued the first of the “Romantic PianoConcerto” series, presenting us with a bevy of19th century composers, many of whommight otherwise have languished inobscurity? The series is still going strong, andat last count, was up to number 64. This year,the company is embarking on yet anotherproject – the “Classical Piano Concerto”series, and this premiere release featuresthree works by the Bohemian composer JanLadislav Dussek (1760-1812) performed bythe renowned British pianist and conductorHoward Shelley whoalso leads the UlsterOrchestra.Born in Čáslav,Bohemia, Dussek wasa truly internationalmusician – one ofthe first – whosesuccessful career as aperformer, composer and teacher took him tothe Netherlands, Paris, London and then backto his homeland before settling in post-revolutionaryParis.The opening concerto on the disc,Op.1,No.3, written before 1783, is a modelAfter two volumes of worksfor violin and pianoJames Ehnes reachesVolume 3 in his series of BélaBartók’s Chamber Works forViolin with a CD featuring clarinetistMichael Collins, pianistAndrew Armstrong and violinistAmy Schwartz Moretti (Chandos CHAN10820). Collins and Armstrong joinEhnes in an excellent performanceof Contrasts, the workBartók wrote for himself, JosephSzigeti and Benny Goodman in1938, and Armstrong accompaniesEhnes in the very brief Sonatina, apiano piece from 1915 heard here ina 1925 transcription (approved byBartók) by André Gertler.The bulk of the CD, though, isdevoted to the 44 Duos for TwoViolins from 1931. Bartók hadbeen asked to transcribe someof his short piano pieces from1908-09, For Children, a collectionthat had been based in parton some of the folk music he had collectedbefore the First World War. He chose insteadto write four books of duets drawing almostexclusively from a wider range of the folktraditions he had encountered at that time.They’re very brief – 28 of them last less thana minute – but anyone who has played themknows that their brevity doesn’t in any wayindicate an absence of interest, mood change,variation or depth of invention.They’re not difficult to play for the mostpart, although the technical level certainlydoes rise the deeper into the set you go, so it’snot so much a case of judging the performanceshere but more one of simply enjoyingthem. And with Ehnes and Moretti you’re interrific hands.By pure coincidence, the batch of CDs thatincluded the Ehnes Bartók also includedTERRY ROBBINSviolists Claudine Bigelow andDonald Maurice in Voices fromthe Past (Tantara TCD0213VFP),a wonderful 2CD set of transcriptionsof the 44 Duos for two violas,but with a startling – and quitestrikingly emotional – addition:32 of the original field recordingsmade by Bartók that supplied theimpetus and the basic material formost of the duos, heard here for thefirst time together on one album.The first CD has a performanceof the 44 Duos with the appropriatefield recording precedingthe corresponding Bartók duo;the words of the songs, the namesof the singers or players, the locationsand dates are all included inthe excellent booklet notes. Thesecond CD is an uninterruptedperformance of the Duos.Obviously, the sound quality ofthe field recordings, made on waxcylinders between 1904 and 1916,is understandably quite poor, andno restoration has been attempted here. Someof the recordings are very rough – almostinaudible in places – but the emotionalimpact of this singing and playing of ordinarypeople from 100 years or more ago pairedwith the music they inspired is enormousand not only sheds fascinating light on thenuances of Bartók’s writing but also imparts asense of nostalgia to the pieces that is heightenedby the darker tone of the two violas.Bigelow and Maurice wisely chose not touse the William Primrose transcription of thework – the only one commercially available,but full of crucial changes Primrose madein an attempt to keep the duos at originalpitch – and opted instead to simply transposethe entire set of duos down a fifth,thus retaining their integrity. Some brightnessis lost as a result – in The Bagpipe andthe final Transylvanian Dance, for instance –but the gain in warmth and depth more thancompensates for this.Listen to the girls collapsing in laughterat the end of their bright, up-tempo song,and then listen to Bartók’s slow, melancholyPrelude & Canon transcription that followsit, simply aching with longing for a rapidlyvanishing past. It will forever change the wayyou hear these remarkable pieces.Glenn Dicterow has just stepped downafter 34 years as concertmaster of the NewYork Philharmonic, and to mark the eventand honour his service the organizationhas issued The Glenn Dicterow Collection(NYP 20140201), a three-volume selection ofDicterow’s live solo performances with theorchestra between 1982 and 2012. Volume 1is available as a CD and download; volumes2 and 3 are available only as downloads fromnyphil.org/DicterowCollection.A beautiful 88-page souvenir bookletcomes with the CD, which features superbperformances of the Bruch G Minor Concerto,the Bartók Concerto No.1, the KorngoldConcerto and the Theme from Schindler’sList, Dicterow getting inside these worksquite wonderfully in really outstandingrecordings.Strings Attached continues at thewholenote.comwith a centennial tribute toPaul Hindemith featuring violist AntoineTamestit, American cellist Michael Samis inhis debut recording with Reinecke’s CelloConcerto, Here Comes the Dance featuringSanta Ferenc Jr. and the Hungarian NationalGypsy Orchestra, Spanish Dances by theBrazilian Guitar Quartet, violin and pianomusic by Gershwin with Opus Two andHaydn concertos performed by violinistMidori Seiler.70 | September 1, 2014 – October 7, 2014 thewholenote.com

of classicism. In only two movements, themusic bears more than a trace of galanterie,not dissimilar in style to Haydn’s divertimentifrom roughly the same period. Shelley’splaying is elegant and precise, perfectlycapturing the subtle nuances of the score. Theconcertos in C, Op.29 (c.1795) and in E flat,Op.70 (1810) are written on a much granderscale. In keeping with the early Romanticspirit of the music, the Ulster Orchestra’swarmly romantic sound is a fine complementto Shelley’s sensitive and skilful performance.These concertos are a splendid introductionto a series which I hope will prove to beas all-encompassing as the first – and bravo toHoward Shelley and the Ulster Orchestra fortaking the lead in such a masterful way.Richard HaskellPaganini – 24 CapricciMarina PiccininiAvie AV2284In his liner notesfor this two-CD set ofPaganini’s Capriccitranscribed for flute bythe performer, JulianHaycock writes: “In[Paganini’s] virtuosohands, music ofunprecedented technicalcomplexity was dispatched with a coolnonchalance that betrayed little of the effortbehind its execution.”Yes, the name Paganini is synonymous withvirtuosity, no end of which Piccinini brings– incredibly fast double tonguing in No.5,brilliant triple tonguing in No.13, admirablearticulation throughout, but particularlyin Nos.15 and 16, fluidity and even fingermovement, used to great effect in Nos.17 and24, the striking use of harmonics in No.18and the ability throughout to bring out amelody in the low register and accompanyit or comment on it with a soft sweet soundin the high.All of the above, however, are mere technicalfoundation for the artistry whichmakes these studies so much more thanjust fodder for developing chops. The musicappears nonchalant, as in the always tasteful,relaxed and never sentimental execution ofthe ubiquitous ornamentation in a way thatreveals unexpected depths of feeling, in theexquisite control of dynamics and the expressivepower that control brings.In the liner notes Piccinini refers to theCapricci as “inspired miniatures of extraordinary… intensity,” going on to say that shewas struck by their expressive range and by“Paganini’s mystic, dark side and … haunting,introspective, tender vulnerability.” In thisrecording she has succeeded in transmittingthis vision of the Capricci. All in all, it is anenormous accomplishment … brava!!Allan PulkerBeethoven – Piano Concertos 3 & 4Maria João Pires; Swedish RSO; DanielHardingOnyx 4125Certainly there is no paucity of finerecorded performances of these twoconcertos. However here we have anoutstandingnewcomer that, forthese ears, sweepsthe field. Over thepast four decades,Pires has establishedherself as a consummateand refinedMozart interpreter,demonstrating a profound musical approachwith playing that is articulate and sensitive.Applied to her Beethoven these qualitiesilluminate in a pure classical Mozartianapproach, particularly in the Third Concerto.In the Fourth the romantic Beethoven breaksout of the Mozartian boundaries. Pires playsthroughout with exceptional taste; it is as ifshe were “talking” the music to us. The resultsare so persuasive that I found myselfrehearing and re-hearing the two performancesand wondering if I would want to listento any other recording of this repertoire.Another of the joys of listening to theserecordings is the complete accord throughoutbetween conductor and soloist. It is a handin-glovepartnership. The style and balancesof the orchestra are very much in the mannerof the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie,Bremen of which Harding was the conductorfrom 1999 to 2003. The performances are wellserved by the splendid production values.Bruce SurteesMozart & Brahms – Clarinet QuintetsAnthony McGill; Pacifica QuartetCedille CDR 90000 147Mozart and Brahms,more or less a centuryapart, wrote quintetsfor clarinet and stringquartet during theirmost mature creativeperiod. While linernotes for this latestrecording draw interestingparallels between them, the pieces arequite distinct. More interesting than materialsimilarities is that both works sprang fromthe composers’ admiration and affection forparticular clarinetists. It is left to the contemporaryperformer to step into the shoes ofAnton Stadler (Mozart) and Richard Muhlfeld(Brahms), to represent an aesthetic span of acentury in the manner of one’s performance.A greater challenge still is making thepieces sound new. Mozart’s K581 is perhapstoo well-known for that. McGill and companykeep tempi brisk, eschew vibrato, remainin tune; they even affect a Viennese waltz inthe second trio. The clarinet tone is clear andyet warm: crystal velvet. The string playing isassured, all gut strings and clear understatement.It is nice to hear a different cadenzain the finale, uttered with flair. Still, I’m leftfeeling that what we have here is another finerendition of a treasured yet worn part of therepertoire, even as I admire the heck out ofthe musicianship.Brahms’ longer and darker work is moredaunting for performer and listener alike.In Steppenwolf Hermann Hesse imaginesan encounter with these composers in theafterlife: Brahms is a Jacob Marley figure(burdened by notes instead of chains); Mozartis the perfect Buddha, free of overstatement.Never mind! The opening of Op.115 is such atremendous joy to hear in all its melancholicbeauty, I forgive the composer his excesses.What a totally ravishing performance is givenon this disc. Bittersweet romance blooms. Thepacing is vital and flexible. Inner voices sing,hemiolas rock. The finale leads to ineluctabletragedy, beautifully. McGill opts for restraintfor too much of the rhapsodic section of theadagio, but on the whole he and the quartetremain true to Brahms’ passionate expression.Buy this recording.Max ChristieSchubert – The Late Piano SonatasPaul LewisHarmonia Mundi HMC 902165.66For explicablereasons I have aspecial affinity forSchubert’s pianoworks, includingthe Impromptus,the MomentsMusicaux andothers, but especiallythe sonatas. Particularly the final threewhich were all composed in 1828, the yearfollowing his visit to the dying Beethoven.Schubert himself was deathly ill but in hislast months he also managed to completethe C Major Symphony, the song cycleSchwanengesang and give a concert onthe anniversary of the death of Beethoven.He died on November 19, 1828 aged 31 andwas buried, as he had wished, very closeto Beethoven in Wahring. In the 1860sboth bodies were disinterred and taken toVienna where they lie, side by side in theCentral Cemetery.Lewis is a front-rank interpreter ofBeethoven as his recordings of the fiveconcertos and the complete piano sonataswill attest, but his realizations of Schubertare no less commanding. He recorded theD784 and D958 in 2013 and the last twoin 2002. Lewis does far more than give usexactly what is written in the score, seemingto express the composer’s own thoughts.This is nowhere more evident than in theopening movement of the D960. A couple ofcomparisons: Clifford Curzon is smooth, fluidand melodic while Radu Lupu is somewhatthoughtful. Neither those nor others has theinnigkeit (sincerity, honesty, warmth, intensityand intimacy) displayed by Lewis. And soit is across the four sonatas. For Lewis thereare no throwaways; every note is significantand important and placed exactly right. Anthewholenote.com September 1, 2014 – October 7, 2014 | 71

- Page 1 and 2:

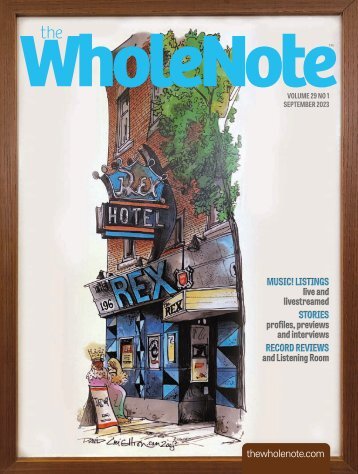

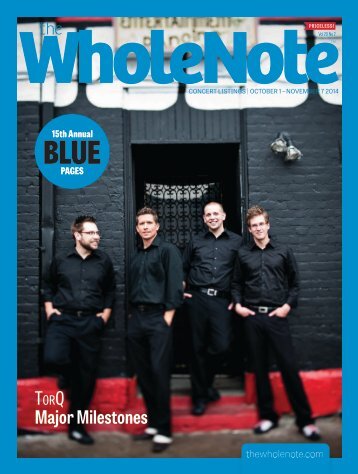

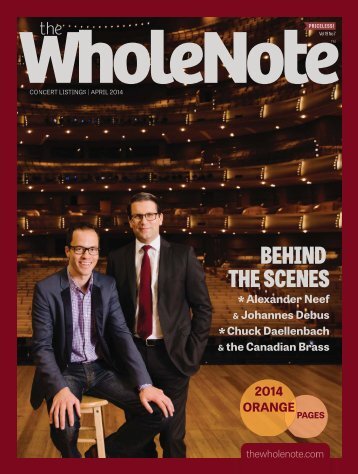

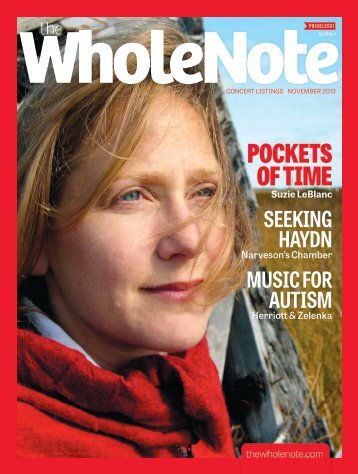

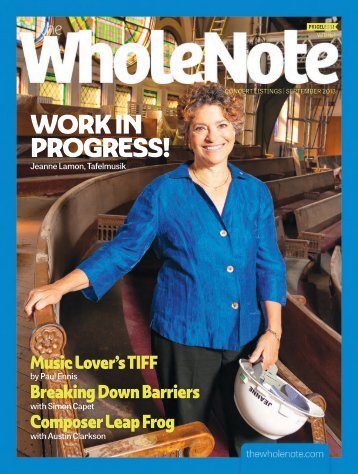

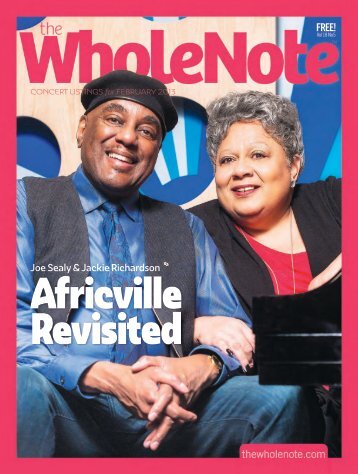

PRICELESS!Vol 20 No 1CONCERT LISTIN

- Page 3:

TORONTO INTERNATIONALPiano Competit

- Page 6 and 7:

FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMANThere’

- Page 8 and 9:

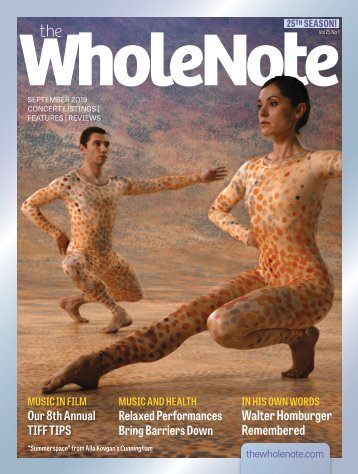

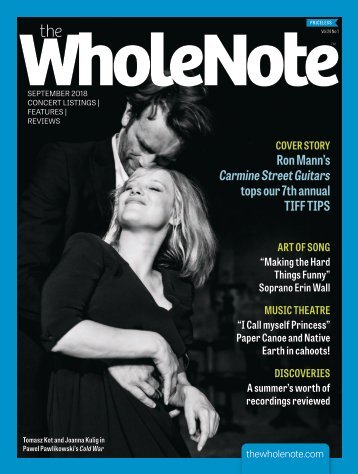

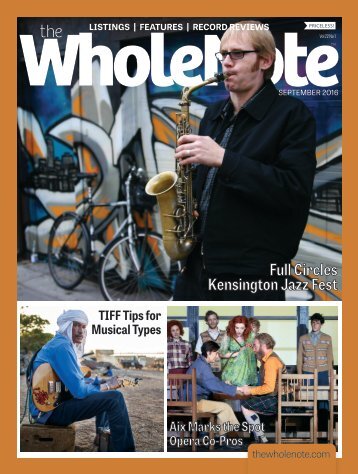

TIFF TIPSBY PAUL ENNISWelcome to Th

- Page 10 and 11:

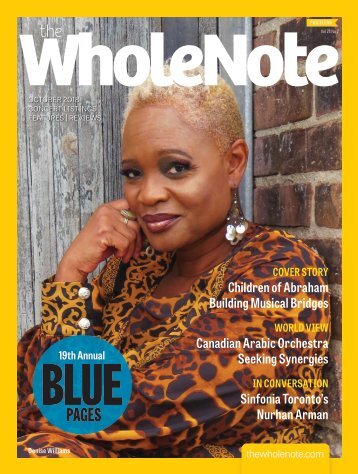

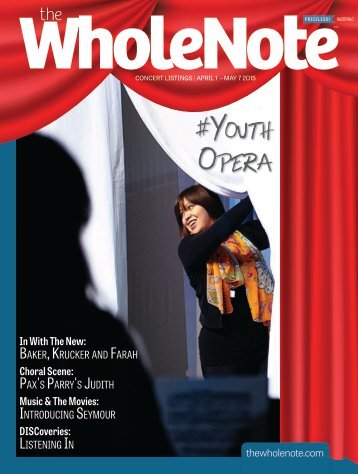

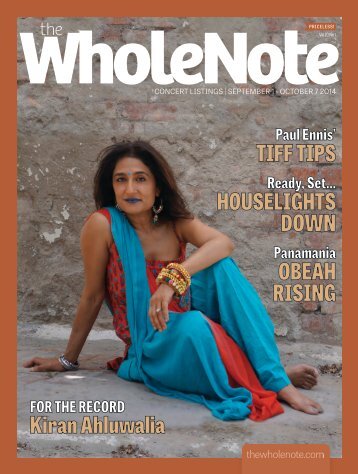

For The RecordKiran AhluwaliaANDREW

- Page 12 and 13:

Ready, Set...Houselights DownSARA C

- Page 14 and 15:

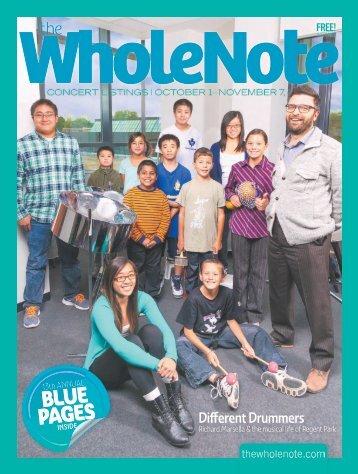

them, and then I facilitate theirwo

- Page 16 and 17:

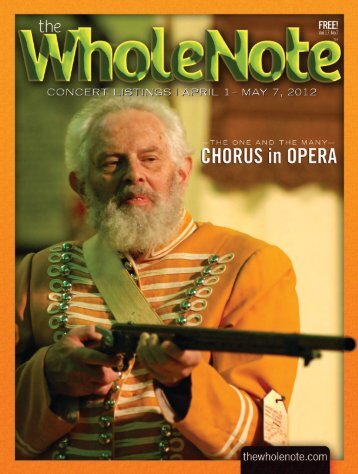

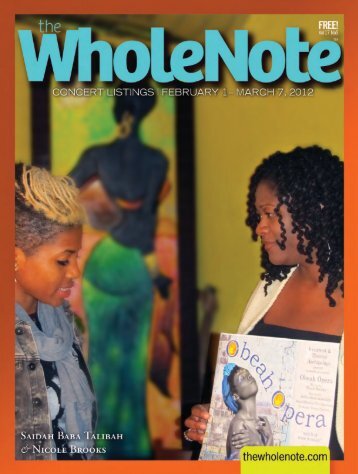

SARAH BAUMANNPanamania-Bound: Obeah

- Page 18 and 19:

MIGUEL-DIETRICHBeat by Beat | World

- Page 20 and 21: Beat by Beat | Classical & BeyondCo

- Page 22 and 23: Glionna MansellPresents14A Music Se

- Page 24 and 25: days later Fewer and the other memb

- Page 26 and 27: ALEXANDRA GUERSONA republic of rich

- Page 28 and 29: space has enabled. One of the major

- Page 30 and 31: Beat by Beat | Art of SongRecitals:

- Page 32 and 33: KATIE CROSS PHOTOGRAPHYAnd beyond t

- Page 34 and 35: music specialist Michael Hofstetter

- Page 36 and 37: Beat by Beat | Choral SceneChoral S

- Page 38 and 39: an Ontario government agencyun orga

- Page 40 and 41: Beat by Beat | BandstandWell Tattoo

- Page 42 and 43: The WholeNote listings are arranged

- Page 44 and 45: ●●7:30: Westwood Concerts. Fair

- Page 46 and 47: Free, donations welcome.●●12:10

- Page 48 and 49: Marques, drums; Michael Shand, pian

- Page 50 and 51: (The Journey). Schubert: Der Hirt a

- Page 52 and 53: B. Concerts Beyond the GTA Beat by

- Page 54 and 55: SAXEBeat by Beat | In the Clubs (co

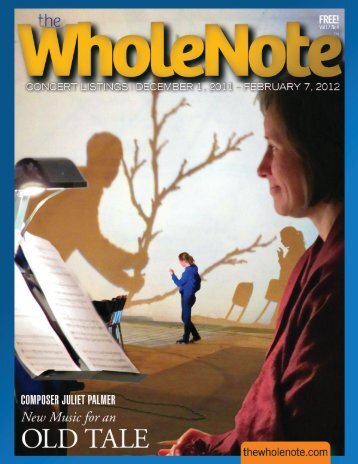

- Page 56 and 57: Of White Nights and Shapeshifting G

- Page 58 and 59: awareness, accessibility, participa

- Page 60 and 61: MUSICAL LIFE: CONCERT DO’S AND DO

- Page 62 and 63: Dis-Concerting continued from page

- Page 64 and 65: SEEING ORANGEdrive me home, stoppin

- Page 66 and 67: DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS REVIEWEDWh

- Page 68 and 69: VOCALAlma & Gustav Mahler - LiederK

- Page 72 and 73: essential recording of this reperto

- Page 74 and 75: Eclectic and artful, Whose Shadow?

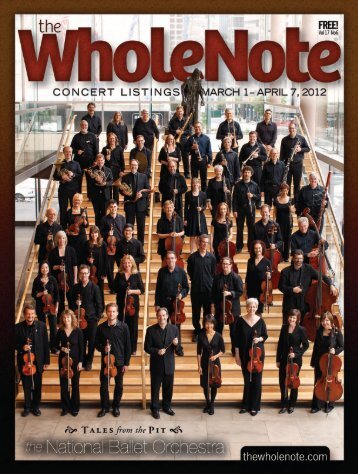

- Page 76 and 77: own and other orchestras, there is

- Page 78 and 79: Tiff Tips continued from pg 9Timbuk

- Page 80: MADAMABUTTERFLYPUCCINIOctober 10 -

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...