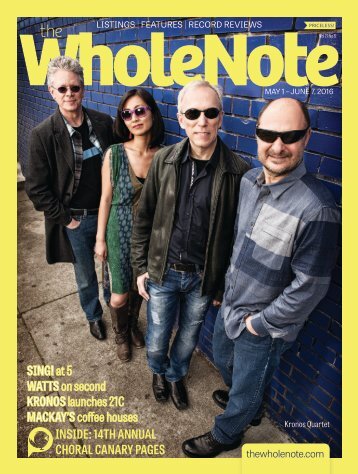

Volume 21 Issue 5 - February 2016

- Text

- February

- Toronto

- Jazz

- Arts

- Symphony

- Orchestra

- Performing

- Musical

- Violin

- Quartet

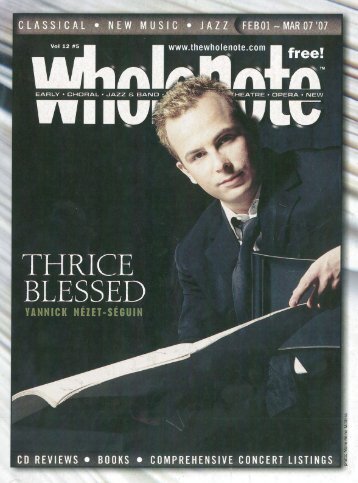

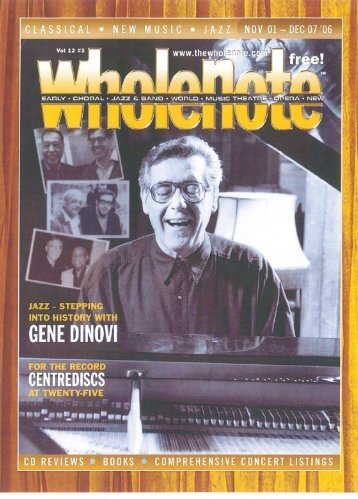

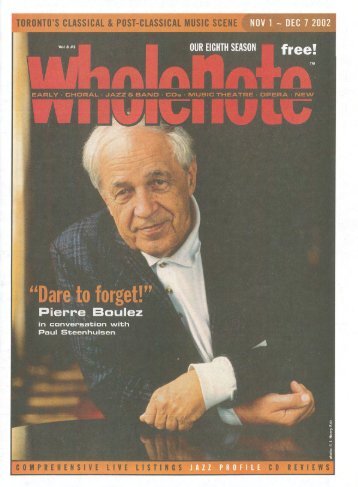

2016 is off to a flying start! We chronicle the Artful Times of Andrew Burashko, the violistic versatility of Teng Li, the ageless ebullience of jazz pianist Gene DiNovi and the ninetieth birthday of trumpeter Johnny Cowell. Jaeger remembers Boulez; Waxman recalls Bley's influence, and Olds finds Bowie haunting Editor's Corner. Oh, and did we mention there's all that music? Hello (and goodbye) to the February blues, and here's to swinging through the musical vines of the Year of the Monkey.

Another session

Another session honouring a departed improviser, but one who was around to participate in this, his final session, is Free Form Improvisation Ensemble 2013 (Improvising Beings ib 40 improvising-beings.com). To be honest, while the hiccupping smears emanating from French-Moroccan tenor saxophonist Abdelhaï Bennani (1950-2015) are interesting as he meanders through these two CDs of linked abstract improvisations, (as is the low-key drumming of Chris Henderson), the focus lies elsewhere. Like famous actors who make cameo appearances in small films, Bennani’s timbral strategy is cushioned or enhanced due to the contributions of American expatriates, pianist Burton Greene, now 78, and Alan Silva, now 76, who plays orchestral synthesizer. Some of Silva’s electronic double-bass approximations give a few of the 13 live improvisations a percussive rhythm that they otherwise lack. Elsewhere the oscillating sheets of sound the synthesizer produces wash over the other players like a cyclone-induced rainstorm. Silva’s blurry processes cascade in such a way to encourage the saxophonist’s harsh interface. But more often than not, whether in tandem with Bennani or on his own, it’s Greene’s considered patterns which pierce Silva’s murky enveloping sounds like a nail through wood. Almost from the beginning, the pianist’s centipede-like reach sharpens the program as he moves along the keys and symbolically within the cracks between them. With oscillating ponderousness on one side and hesitant reed puffs and percussion clatter on the other, it’s Greene who emphasizes the rhythmic thrust at the end of CD1 to create a groove. On the second disc, as Greene varies his attack from impressionistic classicism to Thelonious Monk-like angularity, he brings out sympathetic low-pitched timbres from Silva which encourage the saxophonist’s whinnying cries, and adds some levity via a lively cadenced solo in the middle. By the concluding minutes, Silva’s mass of processing retreats to bring the saxophonist into the foreground. Reading too much into Bennani’s restrained buzzes and puffs may be like those critics who portend the demise of writers by analyzing their final prose, but Bennani’s leaky, brittle tone does appear to be that of a man playing his own threnody. Luckily, the older but more nimble Silva, and especially Greene, are on hand to add palliative empathy. Another improviser whose broad-mindedness and experimentation are not affected by age is saxophonist Joe McPhee, 76, who is recording and playing as prolifically now as he has since he started recording in the late 1960s. Ticonderoga (Clean Feed 345 CD cleanfeedrecords.com) finds him sharing space with a near-contemporary drummer, Charles Downs, 72, as well as pianist Jamie Saft and bassist Joe Morris, who are two or three decades younger. In this classic formation, McPhee glides between tenor and soprano, extruding textures weighty and coarse as lumber, but adding cunning aviary-pitched trills from the smaller horn. Like the mortar that bonds bricks, Downs’ collection of clunks and raps builds a strong foundation able to support any embellished strategy. Similarly, tremolo pulses and bow-sourced sprawls allow Morris to accompany and solo. Though like a tugboat alongside the ocean liner which is McPhee, Saft never abandons the background role. At the same time he uses calming harp-like string plucks and stops as frequently as keyboard tropes. With balladic tones transformed via altissimo screams into daggersharp notes as he plots an original path, the saxophonist’s skill is most obvious on Leaves of Certain and A Backward King. Like a mathematician scrawling numerous formulae on a blackboard, McPhee treats the first as a testing ground for exotic multiphonics, stretching out an assembly line’s worth of reed textures to form variegated patterns. Finally, alongside Saft’s yearning glissandi he settles on dual tones created by shouting into his saxophone’s body tube as he masticates the reed. The result is a finale that satisfies with no letdown in excitement. Cheerful, buoyed by Saft’s guileless patterning, A Backward King initially highlights Saft exposing so many keyboard colours that he could be figuratively knitting a rainbow-dyed scarf. A subsequent processional piano statement presages McPhee’s shift from snarky stridency to gentle ballad variations, until the two swiftly reverse the process like a car backing up, and construct a new garment out of half-puckered sax blasts and half inside-piano plucks. Climatically though, Morris’ background patterning produces a pluck so dexterous and directional that it soothes the others into moderato attachment and then silence. More than 40 years separate South African drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo, 75, and Italian pianist Livio Minafra, 33. But during Born Free (Incipit Records 203 egeamusic. com) the South African-Italian duo produces enthralling episodes of cinched improvisations and compositions. The CD attains its creative zenith on Flying Flamingos. Operating like two halves of a single entity, each man’s measured tones slip into place like the bolt in a lock. Exhorted verbally and by Moholo-Moholo’s jouncing minimal drum patterns, Minafra frames his narrative with rugged honky-tonklike keyboard splashes, only to emphasize a sparkling easy swing in the tune’s centre. This responsive patterning is expressed throughout, as the two move through episodes of almost-Disney-cartoon-like tenderness on a tune such as Angel Nemali; to the repressed ferocity of Foxtrot, where acute drum pummelling and choppy, high-pitched key clattering up the piece’s Charlie Chaplin-like waddle to sprinter’s speed. Like a racing car that accelerates to 160 mph from zero, the two demonstrate similar control on the introductory and closing variations on Canto General, with the pianist’s glissandi at warp speed on the first, and the drummer’s literal collection of bells and whistles prominent on the second. This package also includes a DVD with filmed episodes from the performances plus commentary from both players. During his long career Moholo-Moholo has played in many duo situations including a memorable CD with Swiss pianist Irène Schweizer. Like the other innovators here, Schweizer, 74, divides her work between playing with younger musicians and her contemporaries. Welcome Back (Intakt 254 intaktrec.ch) is titled that way since it’s the second duo CD the pianist and Dutch drummer Han Bennink, 73, have recorded. The first was in 1995. Acting their age, the two breeze through 14 tracks with élan, excitement and empathy. Schweizer’s gracious variations on ditties like Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland are mocked by bomb dropping and whistles from Bennink, but eventually overcome his disruption when she adds a touch of stride. Meanwhile jazz classic Eronel is wrapped up in fewer than two minutes, with the pianist’s pumping percussiveness swinging the contorted line. Like a reveller trying on several masks at a costume party, Schweizer’s original meld of (Thelonious) Monkish angularity, South African highlife and earlier jazz forms are showcased on Kit 4, Ntyilo, Ntyilo and Rag, with the first shapeshifting to staccato hardness abetted by the drummer’s clattering; the second theatrical and respectful, plus ending with the sonic equivalent of a multi-hued sunset; and the last narrative swelling to Willie “The Lion” Smith-style finger-busting swing. She and Bennink confirm their seasoned status on Free for All, gliding over different styles with feather-light key pressure and brush strokes that sound like sand rubbed on the snare, before intervallic leaps expose kinetic underpinnings. But the key track is Schweizer’s own Bleu Foncé. Like a detective series where the characters are known, but surprises appear in every episode, Schweizer’s variations on a traditional blues are true to the form, yet on top of Bennink’s condensed shuffle beat, she adds feints and emphasis to express her creative individuality. George Bernard Shaw once said that “youth is wasted on the young.” In the case of these improvisers though, when it comes to music at least, age is just a number. 66 | February 1, 2016 - March 7, 2016 thewholenote.com

Old Wine, New Bottles | Fine Old Recordings Re-Released Some years ago during the intermission feature on a recorded concert heard on the car radio, the conductor, a prominent figure, spoke about his meeting with Igor Stravinsky of whom he asked about interpreting Le Sacre du Printemps. “Do not interpret my music,” he was instructed, “just play what I wrote.” Who better to do that than the composer himself. Igor Stravinsky – The Complete Columbia Album Collection (Sony 502616, 56 CDs, a DVD and an informative 262-page hardbound book) contains every one of his own and supervised recordings made by American Columbia and RCA Victor. In 1991 Sony issued Igor Stravinsky: The Recorded Legacy on 22 CDs and it seemed this was to be the final chapter on the Columbia recordings. In the intervening years many changes have enabled Sony to add 34 new CDs. Included now are all 19 monaural recordings including the three RCA CDs with the RCA Symphony Orchestra and all the pre-stereo recordings with the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Metropolitan Opera and soloists including Joseph Szigeti, Vronsky and Babin, Jean Cocteau, Peter Pears, Mitchell (later Mitch) Miller, Mary Simmons, Marilyn Horne, Marni Nixon, Jennie Tourel, Bernard Greenhouse, Vera Zorina and many, many others. Each of these recordings is a part of the Stravinsky legacy. Stravinsky’s recording of Le Sacre du Printemps from April 1940 with the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York was the first Stravinsky work I owned. It became my reference performance and is the first disc in this new box. Listening to the 1960 recording of the 1947 version with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra (disc 22) is a different experience. After the back-in-time opening, The Augurs of Spring – The Dances of the Young Girls bursts forth unmistakably as ballet music and not simply a concert piece. Stravinsky’s propulsive beat and accents are maintained through Part One, percussive, but not confrontational nor blatantly aggressive, yet very potent and authoritative. Many, perhaps most, who acquire this new set will enjoy comparing the early to the later performances of other works. Several are of particular interest: the Symphony of Psalms (1946, NYC) versus the 1963 recording with the Toronto Festival Singers and the CBC Symphony Orchestra; also the suite from The Soldier’s Tale (1954, NYC) versus the brilliant 1961 Hollywood complete recording, abstracted as a Suite – later the complete score with narration by Jeremy Irons was issued. The Ebony Concerto’s over-rehearsed, uninspired performance from 1946 with the Woody Herman Orchestra is brought to life in 1965 by Benny Goodman and a jazz combo. Stravinsky is also heard in rehearsals, as pianist and in conversation and in a monologue, “Apropos of Le Sacre,” that clears up a few events. All the monaural recordings, from original discs and tapes, have been transferred employing 24/96 technology resulting in the highest fidelity to the originals. Audiophiles may remember when it was de rigueur to vehemently denigrate Columbia for multi-miking that, they claimed, perverted the real sound. Listening to these priceless, landmark performances in such wide-range, you-are-there 3D realism, will certainly put a lie to that. The accompanying DVD, Stravinsky in Hollywood, is the film by Marco Capalbo that takes us from Stravinsky’s great expectations there in 1939 through to the composer’s last days in 1971 in NYC where he, with his longtime friend Robert Craft, mused over the scores and recordings of Beethoven’s late string quartets. A most unexpected sequence of events occurred last week … I opened the 37-CD reissue of the Quartetto Italiano intending to check out the repertoire and listen to a piece or two for now, intending to get into it later. My big mistake was that I started with the Beethoven Op.132 and Grosse Fuge Op.133. Later became sooner, and sooner became now, and immediately I found myself embarking on the BRUCE SURTEES complete Beethoven cycle, all 16 quartets. From the very first bars their security, their astonishing togetherness and sonorities announce that they are not simply four musicians playing but an entity: a perfect string quartet. The group first met in Sienna in 1942 and in 1945 they came together as the Nuovo Quartetto Italiano, later dropping the Nuovo. They toured extensively and in 1951 they played in Salzburg where they impressed Wilhelm Furtwängler. The conductor convinced them to play with a greater freedom of expression by running through a performance of the Brahms F Minor Quintet with Furtwängler himself at the piano. This was a critical turning point in their career following which they introduced new rhythmic freedoms to their innate classicism. In 1965 they began their long association with Philips recording the Debussy and Ravel quartets. Included in this collection of superlative performances are the complete quartets by Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, Schumann and Webern together with quartets by Haydn, Schubert, Boccherini, Dvořák, etc. and the Brahms F Minor Quintet with Pollini in 1980. The Quartetto Italiano disbanded in 1987. Find complete details of Quartetto Italiano – The Complete Decca, Philips and DG Recordings (Decca 478884) at arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=2158595. As the big-band era passed into history through the 1950s, new schools of jazz had already emerged, from bebop at one end of the spectrum to the cool school. Cool was characterized by easy tempos in arrangements that often had a “classical” feel as exemplified by Dave Brubeck, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Gerry Mulligan and others. Of interest were the various groups formed by Chico Hamilton. Drummer Foreststorn “Chico” Hamilton (1921-2013), in his early musical career, had played with Charles Mingus, Illinois Jacquet, Dexter Gordon and others. Engagements with Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Nat King Cole, Billie Holiday and six years with Lena Horne attest to his proficiency and the inevitability of him forming his own groups. After leaving the original Gerry Mulligan Quartet in 1953, Hamilton made his first recordings for Pacific Jazz as the Chico Hamilton Trio with bassist George Duvivier and guitarist Howard Roberts. So successful was that disc that in 1955 the Chico Hamilton Quintet was formed. “At the outset, I didn’t quite know what I wanted. I only knew that I wanted something new, a different and, if possible, exciting sound.” The quintet comprised cellist Fred Katz; Buddy Collette, flute, clarinet, alto and tenor sax; Jim Hall, guitar and Carson Smith, bass. In 1956 Paul Horn replaced Collette and John Pisano replaced Hall. Their arrangements of original and standard repertoire were all in-house and except for their ghastly versions of all the tunes from South Pacific, the performers communicate a joie de vivre as fresh as yesterday and totally satisfying The1955 to 1959 Quintet recordings are included in Chico Hamilton – The Complete Recordings Volume 1 together with the earlier trio sessions and others totaling 98 tracks (Enlightenment ENSCD9057, 5 CDs). Volume Two contains all 84 recordings by Hamilton’s various groups on assorted labels issued on ten LPs from 1959 to 1962 (Enlightenment ENSCD9058, 5 CDs). Fans of West Coast jazz will get much pleasure from these two sets, as will all those who derive pleasure from cool, chamber jazz. The transfers are exemplary. thewholenote.com February 1, 2016 - March 7, 2016 | 67

- Page 1 and 2:

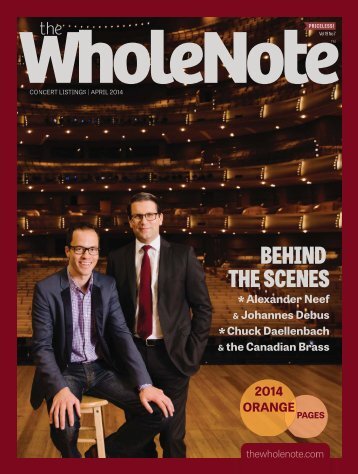

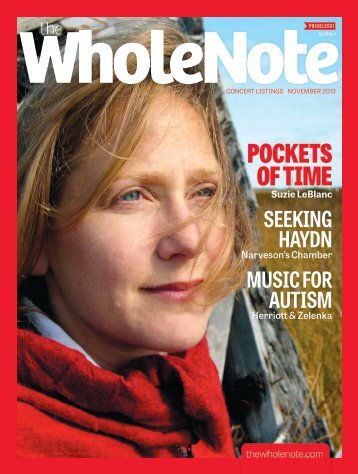

PRICELESS! Vol 21 No 5 FEBRUARY 1 -

- Page 3 and 4:

MUST-SEE FEBRUARY CONCERTS MAXIM VE

- Page 5 and 6:

Volume 21 No 5 | February 2016 FEAT

- Page 7 and 8:

High School Musicality CLAUDE WATSO

- Page 9 and 10:

ST. LAWRENCE QUARTET JOHN LAUENER A

- Page 11 and 12:

the year Burashko’s daughter was

- Page 13 and 14:

Beat by Beat | Art of Song It Takes

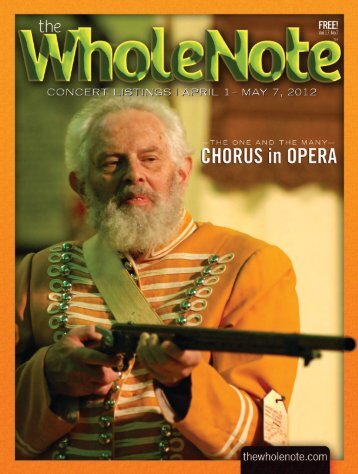

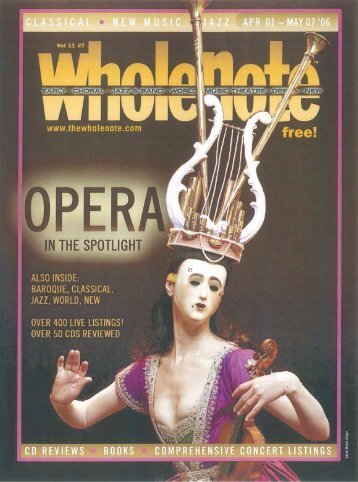

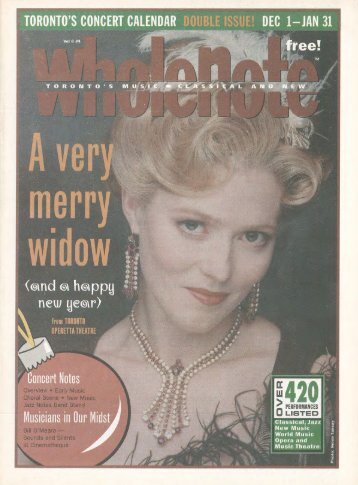

- Page 15 and 16: Sarastro. The Magic Flute runs for

- Page 17 and 18: MARCO BORGGREVE Niles asked Frang,

- Page 19 and 20: Black CMYK Pantone an Ontario gover

- Page 21 and 22: And then there is the Off Centre Mu

- Page 23 and 24: Beat by Beat | Choral Scene The Pow

- Page 25 and 26: Beat by Beat | Bandstand Johnny Cow

- Page 27 and 28: drumpad, a digital hand percussion

- Page 29 and 30: Thursday February 4 ●●12:00 noo

- Page 31 and 32: piano. 345 Sorauren Ave. 416-822-97

- Page 33 and 34: Rodrigo: Concierto de Aranjuez; Tch

- Page 35 and 36: Krisztina Szabo, mezzo; James Westm

- Page 37 and 38: ●●8:00: Toronto Symphony Orches

- Page 39 and 40: Mark Chambers, cello; Maria Case, c

- Page 41 and 42: The Heart. Schumann: Liederkreis, O

- Page 43 and 44: Beat by Beat | Mainly Clubs, Mostly

- Page 45 and 46: 21 Old Mill Rd. 416-236-2641 oldmil

- Page 47 and 48: Rd. 416-597-0485 or cammac.ca (

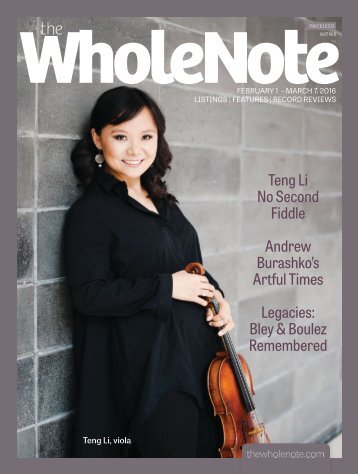

- Page 49 and 50: BO HUANG Teng Li lives in Toronto

- Page 51 and 52: Erickson, which I found myself read

- Page 53 and 54: her stylishness and technical refin

- Page 55 and 56: who collect Goldbergs. Most importa

- Page 57 and 58: and Laetatus sum by the choral ense

- Page 59 and 60: !! There is a difference between th

- Page 61 and 62: musician/activist Victor Jara’s p

- Page 63 and 64: eing inspired by a performance by l

- Page 65: POT POURRI Pillorikput Inuit - Inuk

- Page 69 and 70: KOERNER HALL IS: “ A beautiful sp

- Page 72: 2016 | 2017 SUBSCRIBE AND SAVE UP60

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...