Volume 21 Issue 6 - March 2016

- Text

- Toronto

- Jazz

- April

- Arts

- Theatre

- Orchestra

- Musical

- Symphony

- Performing

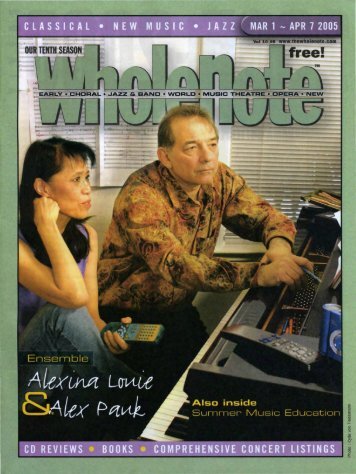

- Ensemble

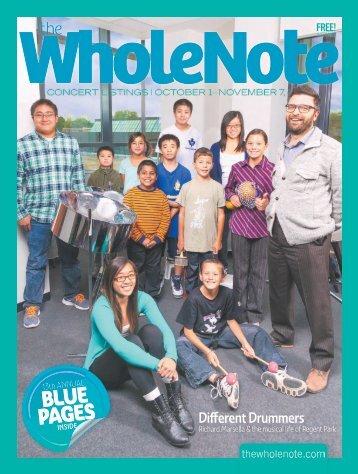

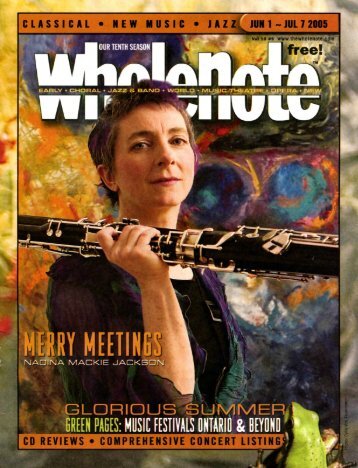

From 30 camp profiles to spark thoughts of being your summer musical best, to testing LUDWIG as you while away the rest of so-called winter; from Scottish Opera and the Danish Midtvest, to a first Toronto recital appearance by violin superstar Maxim Vengerov; from musings on New Creations and new creation, to the boy who made a habit of crying Beowulf; it's a month of merry meetings and rousing recordings reviewed, all here to discover in The WholeNote.

Something in the Air

Something in the Air Young Blood Still Pumps in Jazz KEN WAXMAN Child prodigies really don’t exist in improvised music. Occasionally there may be some youngster known for jazz playing. But unlike other musics which depend on a performer having a cute image or being able to copy what’s on the score paper, improvising demands full exposure of an inner self. Lacking maturity, the majority of these tyros soon disappear. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t young improvising musicians. But to create notable works, like the skills of exceptional actors or visual artists, true musical talent is almost always refined during the player’s 20s or 30s. Take German percussionist Christian Lillinger, 31, for instance. An in-demand sideman and leader of smaller bands for the past few years, the septet he assembles on Grund (Pirouet PIT 3086 pirouet.com) allows him to craft interlocking arrangements for the 11 tunes he composed. Except for his singular incisive drum beats which underline or put into bold face the cumulative sound, Grund is an exercise in parallelism. There are two saxophonists, Pierre Borel and Tobias Delius; two double bassists, Jonas Westergaard and Robert Landfermann; while Christopher Dell’s vibraphone and Achim Kaufmann’s piano are the chordal instruments. Like a well-drilled military unit this is a group effort. Lean and taut, each of the drummer’s tunes is directed from behind via stick-slapping nerve beats, cymbal taps or positioned rolls, allowing Kaufmann’s piano or tongue-slapping reeds to create the declarative theme statement, with Dell’s vibes scattering reflective tone colours like new paint glittering on a surface. Most reflective of the moods the seven engender are the adjoining Blumer and Malm. The latter is pitched so that it sounds like a Jazz Messengers LP played at 45 rpm with Delius’ sharp clarinet tones adding atonality, while the vibes lighten the mood. When barroom piano-styled pumps and dual horn flutter tonguing threaten to derail the narrative, regular drum thwacks push the theme back on track. In contrast Blumer is organized like a gentle chamber piece with first vibes, then piano and finally swaying horns voicing the melody. What could be jejune is transformed as the low-energy narrative is agitated by a clip-clop drum beat. Buzzing dual bass lines, rolling piano chords or atonal sax explorations are prominent elsewhere. But whether the results are balladic or bombastic, the spackle-like fills from Lillinger’s percussion patterns consistently and distinctively glue the parts together. French alto saxophonist Pierre Borel, 28, is also one of the voices in the Berlin-based quartet Die Hochstapler, along with fellow Gaul, trumpeter Louis Laurain, 31; Italian bassist Antonio Borghini, 38; and German drummer Hannes Lingens 35. Dedicated to aleatoric strategies that mix notation and improvisation, Die Hochstapler’s The Music of Alvin R. Buckley (Umlaut ub007 umlautreords.com) is inspired by the probability theory of researcher and musician Buckley (1929-1964) who apparently abandoned music after an encounter with Karlheinz Stockhausen. Never particularly jazzy, although the concluding Playing Cards easily fits into that idiom with walking bass and parry-and-thrust movement from the horns as if participants in a speed-chess match, the CD’s five tunes are instead concerned with how many unexpected strategies can be teased out of an initial theme statement. Lingens’ rhythm accents are placed with clocklike regularity or expressed in free metre to intensify the steaming emotionalism from Laurain and Borel. A further trope slyly combines martial-like beats with oblique exaggerations related to modern chamber recitals. Layered horn tones are particularly evident on…ce que le ver est a la pomme as phrasing ranges from those replicating wind-shaking trees to fortissimo porcine snorts. Elaborating the tune as they deconstruct it, the saxophonist’s squeaks, runs and the drummer’s press rolls move in and out of bop emulation before torrid trumpet toots thrust the piece back to swing underpinnings. Other performances include players lobbing divergent sequences until a melody connects as if plopping pieces in winning order in a game of Chinese checkers. Dribbling reed vibrations, smoothly bowed bass strings and focused paradiddles suggest calming cool jazz swing on every bird must be catalogued; or an unexpected foot-tapping melody can arise after bellicose brass plunger tones and body tube sax growls are regularized into an upbeat theme on le musician est au son. Another musician who has created his own sound is French violinist/violist Théo Ceccaldi, 29, whose quartet on Petit Moutarde (ONJazz JP-001 onj.org), performs music he composed inspired by French director René Clair’s 1924 Dadaist short film Entr’acte. The CD is twice the length of the movie, but its initial tracks are crafted organically enough to accompany the film. (Try it yourself with a muted Internet version of Entr’acte). But Petit Moutarde is much more than that. Balancing his superior training in notated music with the jazz sophistication of Alexandra Grimal, 35, who plays tenor, soprano and sopranino saxophones plus vocalizes wordlessly here, the music isn’t some hybrid jazz/classical soundtrack but a melange that stands on its own. With drummer Florian Satche both time-keeping and layering the tracks with cymbal scratches and other unconventional percussion techniques plus bassist Ivan Gélugne alternating between string slaps and rubbing arco concordance with Ceccaldi or Grimal, visuals aren’t necessary. Although some portions of the tracks are purposefully as herky-jerky as the movements in Clair’s film, overall blistering modernism overcomes bal musette-like nostalgia. Bowed bass strings make a proper backing for the fiddler’s Paganini-like display on Petit Wasabi for instance, as curbed and cantilevered swipes fly with upwards enthusiasm. Double counterpoint from violin and saxophone complement one another like steak and frites on Petit Chipotle, as Grimal’s fragile stutters are reflected by Ceccaldi’s delicate stops. Swing can also be displayed at breakneck speed as on Petit Harissa, when tenor saxophone tonal squirts and fused staccato rubbing from double bass and violin strings join focused press rolls to produce limitless excitement. More excitement is apparent on Green Light (MultiKulti MPTO 12 multikulti.com), where Poles, clarinetists Wacław Zimpel, 32, and percussionist Hubert Zemler 35, play on equal terms with well-known American new music improvisers, clarinetist Evan Ziporyn and guitarist Gyan Riley. Beginning as if the tracks present a sonic slide show of someone’s recent travels, tambura, frame drum and bell-like echoes intermingle with Western chamber music tropes including delicate guitar plinks and reed tone layering. The CD reaches an early climax with the instant composition Chemical Wood, as Ziporyn pecks out spangled bent notes through the harsh continuum created by Zimpel blowing both melody and drone from an alghoza or Punjabi woodwind. Since the idea of Green Light is cooperative not solipsistic, the American clarinetist joins in congruent improvisation with his Polish counterpart on tunes like Melismantra. Backed by hard strokes from Riley’s guitar, reed tones are tensely intermingled, with Ziporyn’s clear tones puffing out lines in unison with Zimpel’s rugged altissimo gulps. Even more cross-culturally cooperative is Gupta Gamini, the Zimpel-composed final track. Processional, with echoes of Polish as well as subcontinent folk music, the narrative is kept in motion by tremolo layering from the two horns. Using electric guitar, Riley’s corrosive licks reverberate like torn electrical wires adding a barbed interface. After a pause, the theme finally relaxes into a coda that is a dual showpiece for the reeds’ spectacular upward flutter tonguing. There's more "... In the Air" at thewholenote.com 76 | March 1, 2016 - April 7, 2016 thewholenote.com

Old Wine, New Bottles | Fine Old Recordings Re-Released Thinking Inside the Box The Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal was known as the best French orchestra outside France, thanks to their conductor, Charles Dutoit and Decca Records. With the death of Ernest Ansermet in 1969 Decca had lost their man-about-French-repertoire and were very concerned about having no long-term exclusive replacement. Ray Minshull, a producer for Decca was visiting an artist in Montreal in February 1980 and, fortuitously, attended a rehearsal with the Montreal Symphony. “Immediately” he writes, “it was apparent that our search was over and that I had stumbled upon the solution to our problem. Within two days an exclusive contract was agreed and the following July we recorded the OSM in a CD of violin concertos with Kyung-Wha Chung, another of Rodrigo’s guitar concertos and Ravel’s complete Daphnis and Chloe. When the new recordings were launched, the reception from both critics and public was so enthusiastic…especially in France and Great Britain that we knew that, at last, we had found what we had missed for so long.” Decca has issued a boxed set of their recordings, simply titled Dutoit Montreal (4789466) comprised of 35 CDs in replicas of the original cover art, an 83-page booklet with recording details, two essays by Ray Minshull and an appreciation by Andrew Stewart. Decca proceeded with its original intention, recording the orchestra playing mainly works by French composers while leaving the German repertoire to others in their stable. In this really impressive collection, therefore, there is no Bach, Beethoven or Brahms although there are four Mendelssohn overtures from 1986 and a 1983 reading of Orff’s Carmina Burana. The discs are arranged by date of recording and here are but some of the highlights. The complete Daphnis et Chloé (1980); Boléro, Rapsodie Espagnole and La Valse (1981); The Three-Cornered Hat and El Amor Brujo (1981); Saint-Saëns Symphony No.3 (1982) and Chausson Symphony in B-Flat Op.20 (1995); the two Ravel Piano Concertos with Pascal Rogé (1982); Respighi Pines of Rome, Fountains of Rome and Roman Festivals (1982); Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (1983); Gaîté Parisienne (1983); Le Sacre du Printemps [1921 version], The Firebird, etc. (1984) and Petrouchka (1986); the Fauré Requiem with Kiri Te Kanawa and Sherrill Milnes (1987); The Planets (1986); Bartók Concerto for Orchestra and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1987); Debussy Images and Nocturnes (1988); Franck Symphony in D Minor and D’Indy Symphony on a French Mountain Air with Jean-Yves Thibaudet (1989); two Tchaikovsky complete ballets, Swan Lake (1991) and The Nutcracker (1992); Piazzolla Tangazo (2000), etc. In addition to the above, there are other major works and about 50 other pieces ranging from Hugo Alfrén’s Swedish Rhapsody No.1 to Ambroise Thomas’ once-popular Raymond Overture. A most desirable and attractive collection. Last year Decca signed a five-year contract with Kent Nagano and the OSM. Emil Gilels (1916-1985) was one of the very greatest pianists of the 20th century. He was born in Odessa the legendary city that produced so many other extraordinarily gifted musicians. Arthur Rubinstein, after hearing the 16-year-old Gilels play in Odessa, proclaimed that “If that boy ever comes to America I might just as well pack my bags and go.” As the liner notes mention, Gilels did and Rubinstein didn’t. Gilels graduated from the Odessa Conservatory in 1935 and moved to the Moscow Conservatory where he studied with Heinrich Neuhaus and later became a teacher there. He won competitions galore and BRUCE SURTEES made his North American debut in 1955 when he played the Tchaikovsky B-Minor Concerto (surprise!) with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. His debut in Britain was in 1959. Acclaimed for his astonishing power and stupendous technique, the depth of his artistry and interpretive insights went unrecognized for a time. He made recordings in Russia and after taking the West by storm in 1955 his name appeared on many labels including EMI, RCA and Westminster (whose issues were of Soviet origin). However, his very best recordings were made with DG who consistently provided the best venues and associates and engineers. They are all in this boxed set, Emil Gilels, The Complete Recordings on Deutsche Grammophon (4794651) with 24 CDs and a 68 page booklet telling all. The superiority of these mighty performances and the dynamics of the recordings immediately put these releases in a class by themselves and they happily remain so in these flawlessly engineered reissues. Here are some examples. All but six of the Beethoven Piano Sonatas. The two Brahms Piano Concertos with Jochum and the BPO; Brahms’ First Piano Quartet with members of the Amadeus Quartet; Chopin, Sonata No.3 and three Polonaises; 20 Grieg Lyric Pieces; Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.27 and Concerto No.10 for two pianos with daughter Elena, both with Karl Böhm and the VPO; Schubert’s Trout Quintet with the Amadeus Quartet. The last seven discs contain recordings derived from the Westminster copies of the Melodiya originals from which the highlight for me is a sparklingly articulate, Prokofiev Third Piano Concerto with Kondrashin and the USSR Radio Symphony Orchestra recorded in March 1955. As an aside, in 1946 the New York Philharmonic Symphony performed the Prokofiev Third under Artur Rodzinski with pianist Nadia Reisenberg who was the only one of the big name pianists prepared to do so. Other disc-mates include an Emperor Concerto with Kurt Sanderling from Leningrad and Kabalevsky’s Piano Concerto No.3 conducted by the composer. Also a wealth of encoretype solos, sonatas and trios with Leonid Kogan, Rostropovich and Rudolf Barshai. Known for his poetic approach, pianist Dino Ciani remains a cult figure since his untimely death at the age of 32 in a car accident in Rome in 1974. Ciani’s recordings for DGG are available on CD and, as is usual with cult figures, his followers seek out releases of his live performances. Following Doremi’s Volume One which includes live performances of the Beethoven First and Third Piano Concertos, Volume Two features a newly discovered live performance in excellent stereo sound from the French radio archives of Chopin’s First Piano Concerto with Aldo Ceccato conducting the ORTF orchestra in the Salle Pleyel in 1971. The performance is very much his own, sensitive and communicating. The rest of this edition (DHR-8044-6, 3 CDs) includes works by Chopin, Liszt, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Tchaikovsky, Bartók and Beethoven…all new to CD. His performances of three Beethoven sonatas live from Verona in 1973 reveal Ciani to be an outstanding Beethoven performer. thewholenote.com March 1, 2016 - April 7, 2016 | 77

- Page 1 and 2:

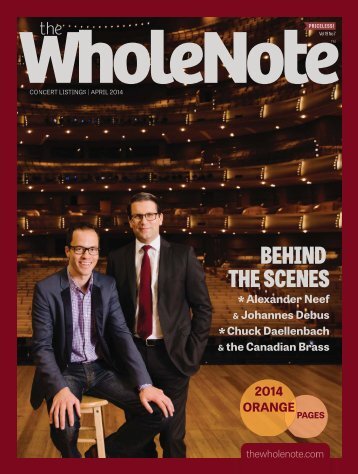

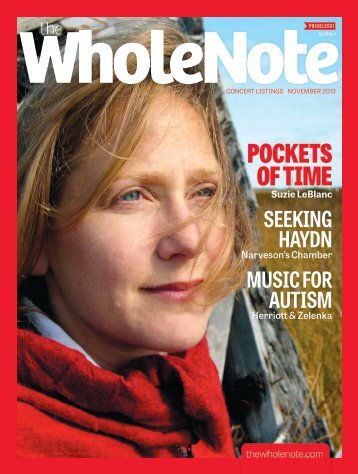

PRICELESS! Vol 21 No 6 MARCH 1 - AP

- Page 3 and 4:

KOERNER HALL IS: “ A beautiful sp

- Page 5 and 6:

Volume 21 No 6 | March 2016 FEATURE

- Page 7 and 8:

Mendelssohn Choir, and a performanc

- Page 9 and 10:

Orchestra under David TORONTO Falli

- Page 11 and 12:

NIKOLAJ LUND Beat by Beat | Classic

- Page 13 and 14:

that illuminates these images. With

- Page 15 and 16:

Brett Dean rehearsing his Viola Con

- Page 17 and 18:

Beat by Beat | Choral Scene Gamers

- Page 19 and 20:

presents a similar program with Cho

- Page 21 and 22:

present the second of this three-co

- Page 23 and 24:

from Schoenberg’s Gurre-Lieder. M

- Page 25 and 26: weston_printad_wholenote3.56x4.95.q

- Page 27 and 28: ORI DAGAN Amanda Tosoff and Galen W

- Page 29 and 30: a special debate to finally permit

- Page 31 and 32: trumpet; James Gardiner, trumpet; J

- Page 33 and 34: musical voices born from the common

- Page 35 and 36: of Toronto, 80 Queen’s Park. 416-

- Page 37 and 38: Hallie Fishel, soprano; John Edward

- Page 39 and 40: ● ● 4:00: Nine Sparrows Arts Fo

- Page 41 and 42: Opera Project. TPC Curiosity Festiv

- Page 43 and 44: ● ● 7:30: University of Toronto

- Page 45 and 46: St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church

- Page 47 and 48: 145 Queen St. W. -5. 416-363-

- Page 49 and 50: Beat by Beat | Mainly Clubs, Mostly

- Page 51 and 52: Paintbox Bistro 555 Dundas St. E. 6

- Page 53 and 54: Classified Advertising | classad@th

- Page 55 and 56: ●●Centauri Arts Camp Wellandpor

- Page 57 and 58: ●●Marjorie Sparks Voice Studio

- Page 59 and 60: apply to volunteer to receive commu

- Page 61 and 62: JOIN US IN RAISING FUNDS AND AWAREN

- Page 63 and 64: At this point the disc takes a hard

- Page 65 and 66: Op.8, presented in its original 185

- Page 67 and 68: needs to proceed and reserves his s

- Page 69 and 70: This recording, nominated for the 2

- Page 71 and 72: Symphony No.4 (1910-16). Each subse

- Page 73 and 74: percussionist/ composer whose CV cr

- Page 75: The Brahms Rondo alla Zingarese is

- Page 79 and 80: international composers Frederic Rz

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...