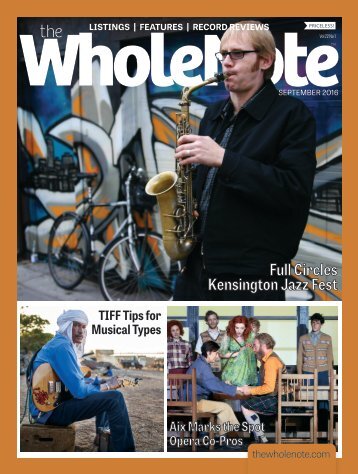

Volume 22 Issue 1 - September 2016

- Text

- September

- Toronto

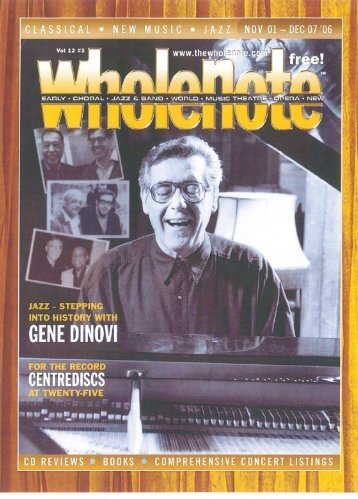

- Jazz

- October

- Festival

- Symphony

- Musical

- Orchestra

- Theatre

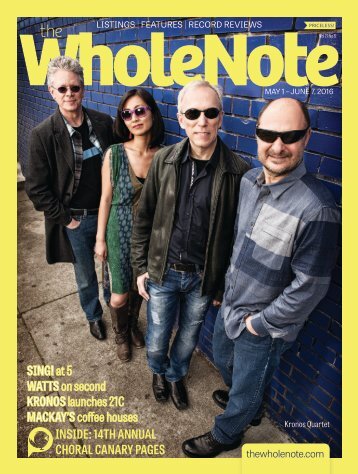

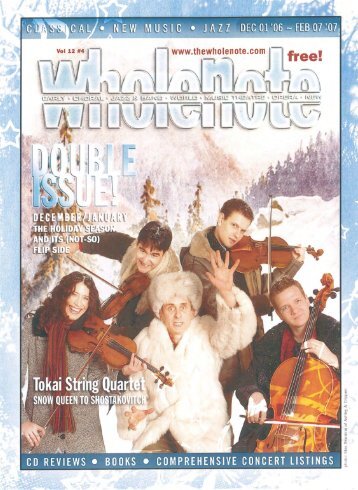

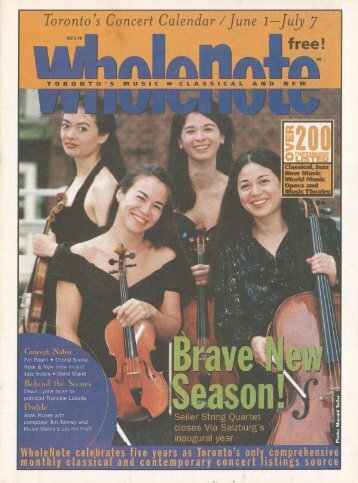

- Quartet

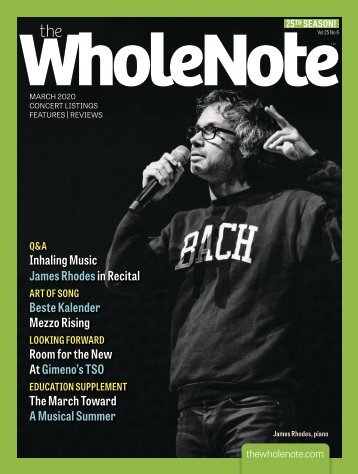

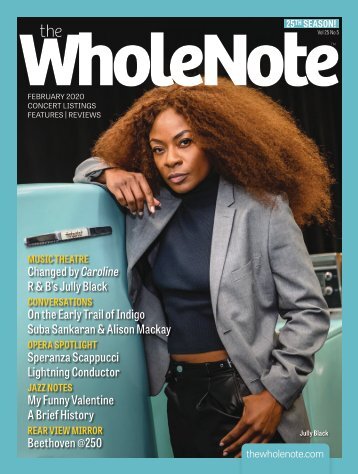

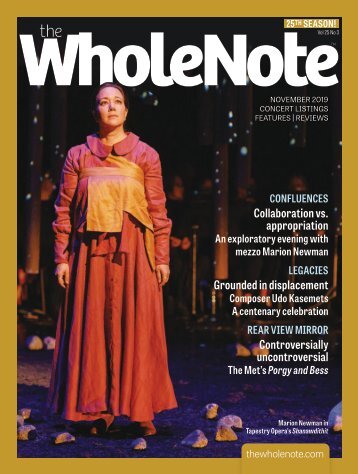

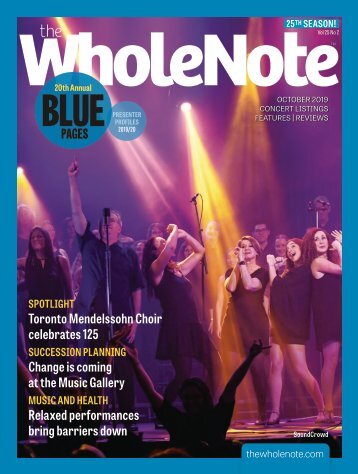

- Volume

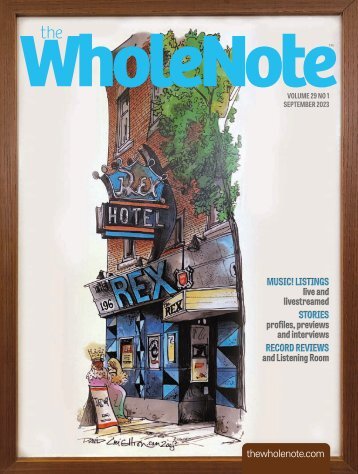

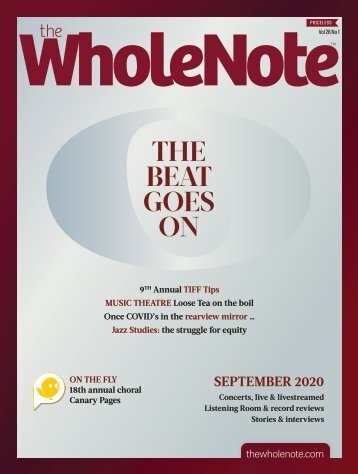

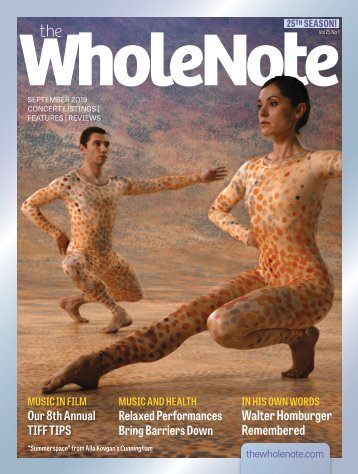

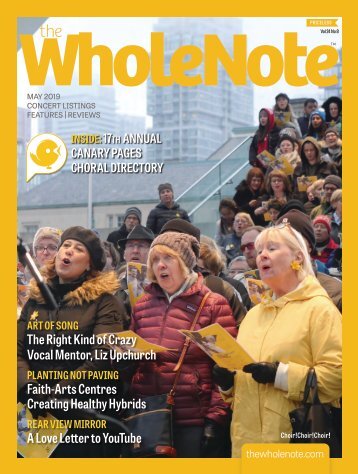

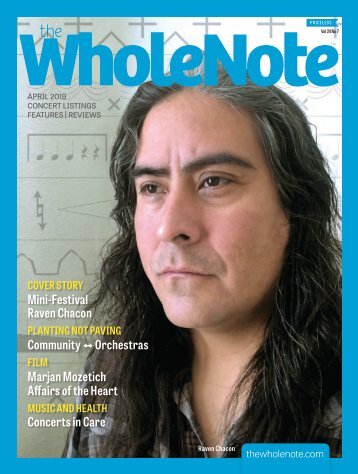

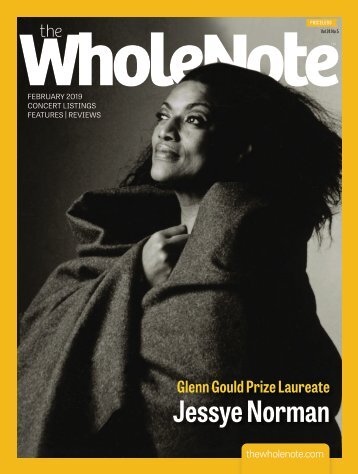

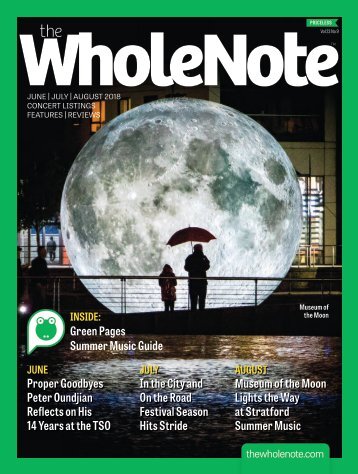

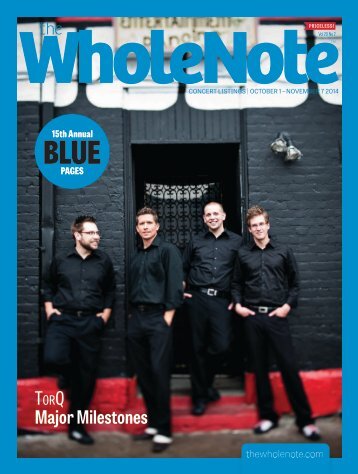

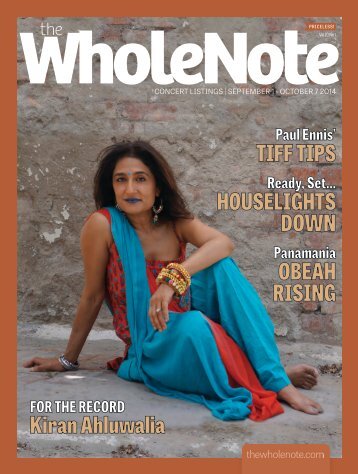

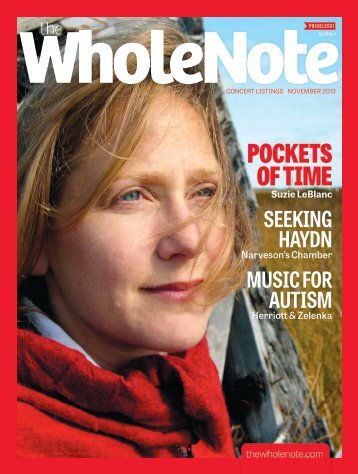

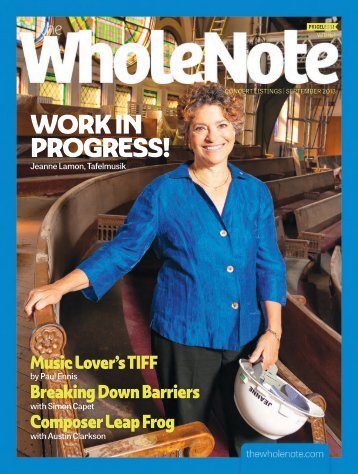

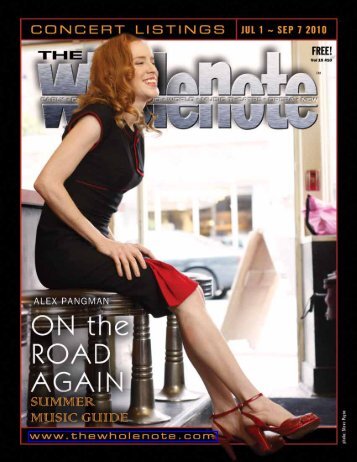

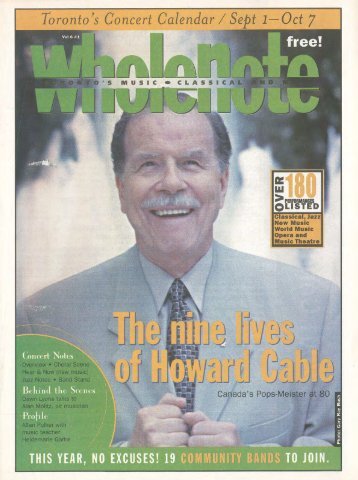

Music lover's TIFF (our fifth annual guide to the Toronto International Film Festival); Aix Marks the Spot (how Brexit could impact on operatic co-production); The Unstoppable Howard Cable (an affectionate memoir of a late chapter in the life of of a great Canadian arranger; Kensington Jazz Story (the newest kid on the festival block flexes its muscles). These stories and much more as we say a lingering goodbye to summer and turn to the task, for the 22nd season, of covering the live and recorded music that make Southern Ontario tick.

Beat by Beat | Early

Beat by Beat | Early Music Bilson to Botticelli Fortepiano Renaissance DAVID PODGORSKI But for a few instances of momentary curiosity of a few brave, or possibly foolhardy, musicians, modern concert audiences might have never heard the sound of historical instruments at all. A great case in point is the pianist Malcolm Bilson’s discovery of historical keyboards back in 1969. When Bilson decided to give a concert on “Mozart’s piano” the result was very nearly a disaster. “I have to admit now that I really couldn’t handle the thing at all,” Bilson said in a lecture. “I must be the least gifted person for the job: my hands are too big, and I don’t have the necessary technique such an instrument required. In trying to operate this light, precise mechanism, I really felt like an elephant in a china closet. But I kept at it all week and practised hard and after several days began to notice that I was actually playing what was on the page. Suddenly I found that I really didn’t need much pedal and that the articulative pauses actually made the music more expressive.” Concert audiences and audiophiles should certainly be grateful that Bilson persevered – he was one of the first 20th-century fortepianists, and without him it’s doubtful we’d even hear a fortepiano today. We’re also kind of fortunate Bilson opted to try using a fortepiano in the first place – the instrument itself is something of an oddity. Even to its inventor, it couldn’t have been considered to have much potential – it was initially a research and development project for the wealthy Florentine Medici family by the Italian instrument maker Bartolomeo Cristofori way back in 1700. Cristofori fit the stereotype of the eccentric inventor quite well indeed. As if inventing a new keyboard instrument wasn’t ambitious enough by itself, Cristofori also tried making harpsichords out of ebony as well as building his own upright harpsichords from designs by other inventors. It’s not known what Cristofori’s patrons thought of the instrument, but it was likely positive, as he continued to develop his invention over the next 20 years and the technology and building of pianos spread across Europe. By the 1730s, J.S.Bach had a chance to play one and recommended the builder make changes (which out of respect for the composer’s expertise, he duly did, much to Bach’s satisfaction). Still, the harpsichord was generally regarded as the superior, or at least, the more affordable, of the two keyboard instruments until the century’s end. In the classical era, Haydn composed for the harpsichord for most of his early career, and wouldn’t buy a fortepiano until he was in his 50s, but Mozart, being 20 years younger, would come to favour the fortepiano exclusively. Just 50 years after Haydn’s death, pianos were becoming louder, more uniform in sound and more durable – and with the coming of the Industrial Revolution, mass-produced in factories and available to a middle-class market. Andrea Botticelli: The fortepiano revival owes much to that first adventurous concert Malcolm Bilson gave in 1969, and there’s been a steady increase in fortepiano players since, but there hasn’t been a professional fortepianist who’s called Toronto home until now. Andrea Botticelli is a recent graduate of the University of Toronto’s doctoral music program in piano performance who has decided to specialize in fortepiano and Classical repertoire. Like Bilson, Botticelli found playing a different instrument to have an almost immediate effect on her interpretation. “Playing a fortepiano was such an eye-opening experience,” Botticelli says. “All the performance issues that are such a struggle on the modern piano – texture, clarity, balance between the hands – become so much easier on the fortepiano.” According to Botticelli, all the exacting details that composers like Mozart and Schubert took such care in writing, all those little slurs, phrase markings and articulations that pianists struggle with, were actually written for the old 18th- and 19th-century instruments, and a modern A copy of a Cristofori fortepiano. Steinway can’t really negotiate the difficult terrain as easily. “So much of what I was trying to add in terms of expression is really inherent on this instrument,” she says. “Once I really started playing the fortepiano, I wondered how I could have gone through a whole undergraduate degree without ever having heard one.” Botticelli will be making her solo debut later this month at the Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts on September 24 at 6:15 pm, playing fantasies by Mozart, Haydn and Hummel, as well as a Mozart piano sonata. It’s really about time there was a resident fortepianist in the GTA, and the fact that Botticelli is willing to base herself in Toronto is yet another sign that the local arts scene has grown to world-class size. There’s been a steady creep of historically inspired practice around the world since the 1970s from medieval/renaissance repertoire through the Baroque period and well into the 19th century, and professional fortepianists have been starting to pop up in major cities around the world in recent years. It’s as if an extinct species has been found again in the wild and is starting to propagate. Like audiences in London, Amsterdam and Vienna, Torontonians will now be able to hear period performances of classical and romantic keyboard music on this compelling period instrument. Christophe Coin: There are few musicians worldwide as accomplished as Christophe Coin. A gambist, cellist and protégé of Jordi Savall since the mid-70s, Coin has gone on to record over 50 albums ranging from Gibbons’ consort music to Schumann’s cello concerto. Coin also directs the Ensemble Baroque de Limoges and is the cellist for Quatuor Mosaïques, so he’s quite adept in conventional baroque and classical repertoire. It will be exciting to see him as both musical director and soloist for Tafelmusik in their upcoming concerts October 5 to 9 at Trinity-Saint Paul’s Centre. It’s clear from this program that Coin is no slouch as a soloist – he’ll be playing both a Boccherini and a Haydn concerto – and he’ll also be leading the orchestra in symphonies by C.P.E. Bach and Dittersdorf – repertoire that both Tafelmusik and Coin excel at. If you’re at all interested in classical music, this is a concert well worth attending. Rezonance: Finally, if you’d like to hear a chamber music concert this month, or just want to get out of the concert hall for a change, consider making it out to hear my group Rezonance Baroque play the music of J.S. Bach at the CSI coffee pub at 720 Bathurst St. (home base of The WholeNote), on September 25 at 2 pm. After Bach settled in Leipzig as the resident music director of St. Thomas’s Church, he was left without a venue to perform any of his secular compositions or chamber works. Fortunately for the master, Gottfried Zimmermann, the owner of the local café in Leipzig, was already one of the hottest music venues in town. Rezonance will perform an all-Bach program that could have easily been heard at Zimmermann’s, including a cantata he composed for the café in honour of coffee. While it’s easy to imagine Bach as overwrought, overworked, and dependent on a caffeine fix to get through the day, this concert features exciting and whimsical repertoire that shows that the brilliant composer may have had a sense of humour after all. David Podgorski is a Toronto-based harpsichordist, music teacher and a founding member of Rezonance. He can be contacted at earlymusic@thewholenote.com. 34 | September 1, 2016 - October 7, 2016 thewholenote.com

Beat by Beat | World View Nostalgia Sure Ain't What It Used To Be ANDREW TIMAR In my summer 2016 WholeNote column I mused on Luminato’s repurposing of the cavernous decommissioned Hearn Generating Station. Would it work as a venue for symphony orchestra, for community cultural engagement, visual art, for Shakespeare? In the end, the capacious, though out-of-the-way, venue turned out to be a gamble that paid off handsomely for Festival organisers as well as for concertgoers. It appears to be part of the continuing recognition in our collective urban zeitgietst of the importance of reclaiming, revitalizing and honouring Toronto’s industrial-commercial past. In September it’s the turn of another large scale 20th-century manmade structure to be repurposed as an artistic venue. Originally opened on May 22, 1971, Ontario Place, the government of Ontarioowned amusement park, was imposed into Lake Ontario, sited on three artificially constructed and landscaped islands. The futuristic buildings and entertaining amenities along Toronto’s shoreline included the world’s first IMAX theatre, the geodesic-domed Cinesphere, and the province’s first waterpark. Some of us old enough to have attended concerts there might fondly recall the spacious, leisurely rotating stage of the Forum. It’s where I took my young kids for free summer concerts, including the memorable time we saw jazz great Miles Davis and his band. We bonded over cool jazz with attitude that sunny afternoon. Then early in 2012 most of the public sections of the park were closed for redevelopment – its 2017 projected completion date aimed to celebrate Canada’s sesquicentennial. in/future: After the venue has been shuttered for four years, Art Spin in partnership with Small World Music is re-animating Ontario Place’s scenic 14-acre West Island. They’ve cooked up an ambitious menu consisting of 11 days and nights of arts programming from September 15 to 25, dubbing the festival in/future. Wishing to dig deeper, I spoke to Small World’s executive director and in/future co-curator Alan Davis one hot sunny summer day. “It’s the 15th anniversary of Small World’s fall festival,” Davis began, “and we’re delighted that Art Spin invited us to showcase part of our current season at in/future.” Art Spin – Layne Hinton and Rui Pimenta’s brainchild – has been active as a presenter for over seven years, re-activating decommissioned venues and public spaces to produce group exhibitions along with curated bicycle-led art tours. “The festival will host site-specific projects by over 60 visual and sound artists,” Davis continued, “with close to 50 music acts on the Small World stage (presented by Exodus Travels).” Films and videos will also be presented in the Cinesphere, as well as dance performances, a lecture series, and kid-friendly programming and activities at BaBa ZuLa various sites. “We’re excited by this opportunity to connect with the larger community. Nostalgia for Ontario Place’s illustrious musical past is one part of the draw, but so is engaging with young audiences. For example, site DJ activations will encourage a party vibe.” “We have also tried to squeeze the envelope with regard to genres, to mix things up, to embrace the entirety of the global musical spectrum. Cross-fertilization is one of the things we’re aiming for. Though it’s easy to say, it’s hard to do,” he added with a knowing smile. I asked Davis to pick a few highlights. “We are leaning toward highenergy, festive acts suitable for an outdoor stage. An example would be BaBa ZuLa, Istanbul’s legendary psychedelic dub band, which takes the stage Friday September 16 with a wide variety of influences and a truckload of instruments. They are followed by Mariachi Flor, a feminist Mexican mariachi group based in New York” he explained. Saturday September 24, at the other end of the festival, is a day so chock full that space here permits only a partial mention. Headlining is the Dhol Foundation, a leading bhangra band making its Canadian debut. It’s led by the U.K.- born master-dhol drummer and artistic director of the group, the “bhangra king” Johnny Kalsis. His Londonbased 12-piece band, which he first established about 17 years ago, places the musical focus tightly on the massive sound of closely miked multiple dhol drums, those icons of Punjabi bhangra music. Kalsis has since waded into transnational waters by fusing bhangra with a mixed bag of popular global genres including Afrobeat, reggae, hip-hop, EDM, and Bollywood with a Celtic fiddling twist. The resulting thumping beats are designed to lift audiences’ spirits, moving everyone to dance. Also performing on September 24 is the Shanbehzadeh Ensemble. It was formed in 1990 by Saeid Shanbehzadeh, a virtuoso of the neyanbān (Persian Gulf bagpipe) and the ney-e jofti (Persian Gulf double reed pipe). He is well known as a forceful performer of the traditional song, music and dance of the southern Iranian province of Bushehr, on the Persian Gulf. It’s a region of Iran strongly influenced by African as well as Arabic culture, and its music and dance amply demonstrate those influences. Shanbehzadeh is no stranger to Toronto. In 1996 he taught a world music studio course at the University of Toronto and at the time I was impressed with his brilliant and charismatic solo performances, full of the feeling of his thewholenote.com September 1, 2016 - October 7, 2016 | 35

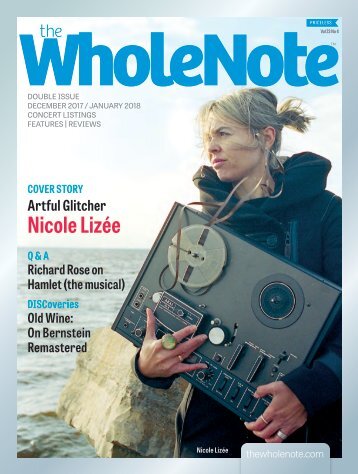

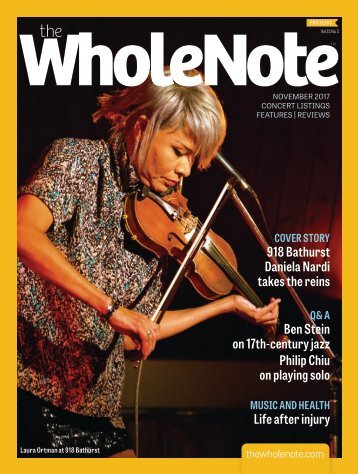

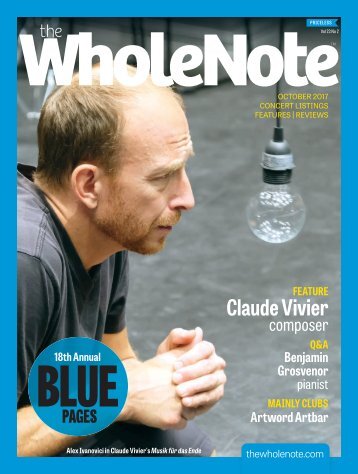

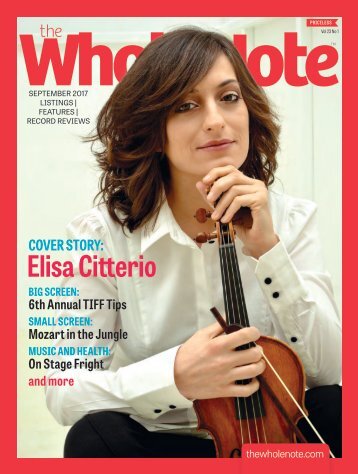

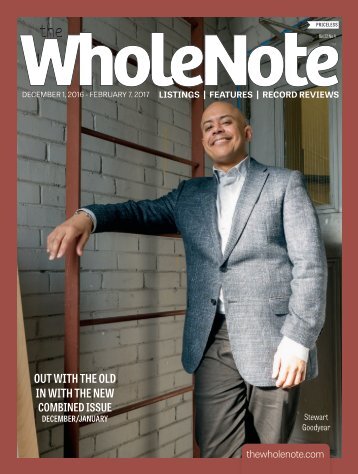

- Page 1 and 2: LISTINGS | FEATURES | RECORD REVIEW

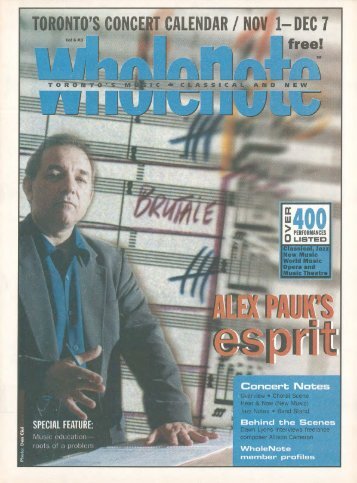

- Page 4 and 5: ESPRIT ORCHESTRA 2016-2017 Season A

- Page 6 and 7: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Ten Yea

- Page 8 and 9: WHEN IT COMES TO OPERATIC CO-PRODUC

- Page 10 and 11: Aix's Axis North-South Reset Kalila

- Page 12 and 13: Aquarius COURTESY OF TIFF 2016 PREV

- Page 14 and 15: COURTESY OF TIFF La La Land Carmen,

- Page 16 and 17: WHAT MOLLY WANTS, MOLLY GETS CHRIS

- Page 18 and 19: SOPHIA PERLMAN - MARKET BORN Beat b

- Page 20 and 21: Michael Mori, artistic director, Ta

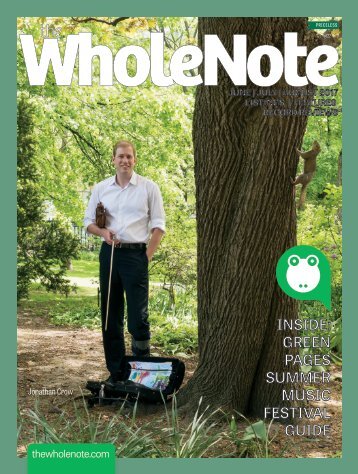

- Page 22 and 23: The eyes have it: Jonathan Crow lea

- Page 24 and 25: well-received TSM recital at Koerne

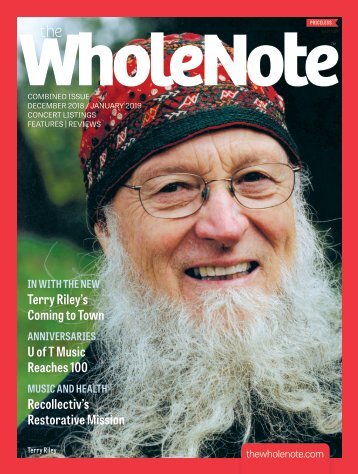

- Page 26 and 27: Beat by Beat | In with the New A Fu

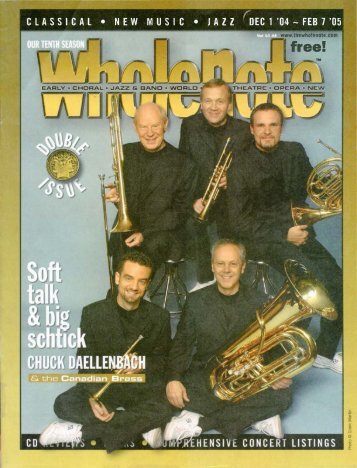

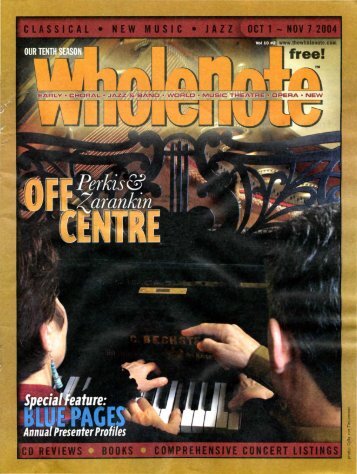

- Page 28 and 29: Inna Perkis & Boris Zarankin FOUNDE

- Page 30 and 31: Beat by Beat | Choral Scene Forward

- Page 32 and 33: listener’s ears to hear these lin

- Page 36 and 37: Beat by Beat | Bandstand Cable Trib

- Page 38 and 39: The WholeNote listings are arranged

- Page 40 and 41: Nicholas Anglican Church, 1512 King

- Page 42 and 43: Church, 1585 Yonge St. 416-241-1298

- Page 44 and 45: W. 416-631-4300. PWYC. Lunch and sn

- Page 46 and 47: ●●Soulpepper Concert Series. Ta

- Page 48 and 49: of Fiddlers Green .50(adv)/(d

- Page 50 and 51: 91 Charles St. W. 416-585-4585. .

- Page 52 and 53: REMEMBERING The Unstoppable Howard

- Page 54 and 55: WE ARE ALL MUSIC’S CHILDREN We Ar

- Page 56 and 57: TERRY ROBBINS If you’re a fan of

- Page 58 and 59: concert in San Francisco on June 26

- Page 60 and 61: this brevity with heightened intens

- Page 62 and 63: way Bondy presents the members of t

- Page 64 and 65: will be. EMI had recorded the compl

- Page 66 and 67: assemblage of accomplished musician

- Page 68 and 69: sustained attentiveness to still in

- Page 70 and 71: Corea. A dynamic, intricate and ful

- Page 72 and 73: !! I cannot think of anything more

- Page 74 and 75: y Americans such as drummer Sam Woo

- Page 76 and 77: continued from page 10 Ariodante au

- Page 78 and 79: LARISSA BARLOW/BANFF CRAG & CANYON

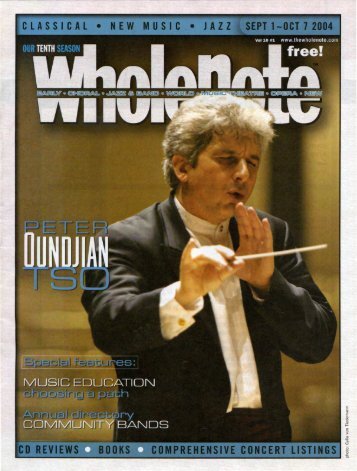

- Page 80: TS Toronto Symphony Orchestra Openi

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...