Volume 22 Issue 3 - November 2016

- Text

- November

- Toronto

- December

- Jazz

- Symphony

- Arts

- Performing

- Faculty

- Theatre

- Musical

- Volume

- Thewholenote.com

for her, a key goal of

for her, a key goal of Euterpe, and of the work that Ensemble Vivant does alongside it, is ensuring that those who otherwise wouldn’t have access to high-calibre concert experiences get the same types of music-making and concertgoing opportunities that made such a difference in her own life. In terms of her own life in music today, Wilson recognizes the health threats of performing professionally, but maintains that seeing the healing benefits of music in action through her Euterpe research and performances provides ample motivation for seeking and finding solutions. “There are a variety of physical stresses to being a concert pianist. Staying healthy physically, avoiding injuries and not becoming too worn down is always a challenge,” Wilson explains. “I swim regularly and see a top physiotherapist. I have endured several long-term setbacks over the years…yet it is music that has always been my main source of psychological strength. Industry stresses, physiological and psychological stresses notwithstanding, the music-making is a labour of love…and is what excites us and keeps us healthy. Giving through music is healing and enriching for our audiences, as well as for us.” Ensemble Vivant’s tour begins in Orillia on November 27 and travels across the province, wrapping up on December 23 in Ottawa with the Cross Town Youth Chorus. For details on the tour, visit ensemblevivant.com. Artist’s Health: I first visited the Artists’ Health Centre this summer, when a sudden change in my work schedule led to a minor injury in my wrist. Becoming aware of the services and the resources they offer for artists of all disciplines has been hugely helpful – both for managing the healing of my own injury and for navigating how musicians can become more open generally about challenges with mental and physical health. Based out of Toronto Western Hospital and run in partnership with the Artists’ Health Alliance, the Al and Malka Green Artists’ Health Centre is a clinic offering both medical and complementary care for professional artists. Patients must selfidentify as creative professionals and meet at least one of the centre’s requirements for what constitutes being a professional artist. Services include acupuncture, chiropractic medicine, craniosacral therapy, registered massage therapy, physiotherapy, psychotherapy (for individuals and in groups) and shiatsu therapy – all with a special focus on accommodating the career paths, lifestyles and income levels of professional arts workers. Susannah McGeachy, the clinic’s nurse practitioner, is typically a musician’s first one-on-one contact with the Centre. Her job, which includes assessing the client’s needs, referring them to other centre professionals and giving them interim guidance on how to manage their condition, means that she sees a lot of different professional musicians – with a lot of different complaints. “I deal with a wide variety [of issues], but there are certainly recurrent themes,” says McGeachy. “I would say that generally, soft tissue injuries are pretty common – things like sprains and strains that aren’t always allowed to rest and heal the way that they need to because of the demands of a musician’s professional practice. Things like chronic tendinitis – broadly, we call them overuse injuries, where you can get inflammation and damage from using a very small muscle group to do the same kind of motion again and again, many times. Another thing that comes up often is the challenges that musicians face around mental health and anxiety, sometimes associated with what I call being in ‘constant evaluative situations’ like auditions and performances, with a certain level of career unpredictability.” With the level and volume of issues that McGeachy sees, it’s clear that our music industry needs to change – both in the way it employs musicians and in the stigmas in the performing arts around prioritizing self-care. “I know it’s a complex thing,” McGeachy says, “but I think that with performance and rehearsal scheduling, more attention and awareness needs to be paid to the physical demands on the “Your body is your instrument as much as your instrument is your instrument...an even more intricately made instrument than the one that [you’re] playing.” musicians – who are often performing a lot of very different repertoire in a short period of time, and having these ‘bursts’ where there’s a lot of physical demand, both in terms of the pieces themselves and the travelling that musicians have to do. I think with orchestras, for example, and even sometimes in educational institutions, the work happens with much more regard to venues, conductor availability, and things like that – but it doesn’t always seem like there’s an eye on getting a good balance of repertoire – physically – and giving the musicians rest and recovery time. “There’s this idea in the music industry,” McGeachy continues, “that it’s important to play as many gigs as you can, and that however those fall, the musicians are just sort of expected to rise to the challenge. And I think that systemically, that makes it very hard for individual musicians to know how to take good care of themselves.” And as for advice to musicians, about how they can focus on selfcare, and why it matters? “Your body is your instrument as much as your instrument is your instrument,” says McGeachy. “If you think about the care and attention that a musician gives to making sure that their instrument is well-tuned and protected and not exposed to the elements...what I think musicians don’t always realize is that they are an even more intricately made instrument than the one that they’re playing. And that really to make a long-term career out of this work, it’s important to learn your body as early as possible. It’s about forming practices that will allow you to do what you love for as long as you want. “Overall, I think the biggest message that I try to drive home with musicians is to learn to listen to their bodies,” she says. “To not play through pain. To break up practising into shorter sessions, especially if something hurts. And to warm up: I think that musicians often think of musical warm-up but not physical warmup. Before playing, it’s important to do some physical warm-up to increase your heart rate and circulation – a brisk walk, jumping jacks, or a few flights of stairs. It sounds silly, but it’s pretty basic physiology – it decreases the risk of injury. And otherwise, musicians are people too, so doing the things that are good for everybody: regular exercise; a well-balanced diet; drinking lots of water; and doing things that you love, and promoting your own balance and mental health.” McGeachy also mentions that her door is often open and that the Centre is always happy to see people (artistshealth.com) – so musicians, if you’re ever in need, be sure to look them up. The potential for music-making to act as a healing experience for people – and the potential for a musical career to become mentally and physically unhealthy as well – is worth discussing. If you have your own story about music and self-care, as a musician, or as a listener, feel free to send it along, to editorial@thewholenote.com. I’m sure that there will be others who can relate. I’ve dealt in the past with injury and anxiety, and it isn’t an easy subject to communicate about. I’ve known professional musicians who have neglected their well-being because they felt that self-care was fundamentally at odds with living in the service of their craft. I’ve known music students who have been reluctant to tell teachers about playing while hurt, because they were afraid to be seen as a liability within their studios. Unless performers and listeners keep having conversations about how music affects the minds and bodies of people, for better and for worse, it will remain difficult for people to recognize that self-care and musical commitment need not be at odds with one another. In fact, for many professionals, those two things make the most sense when they can feed off of one another. Let’s get talking. Sara Constant is a Toronto-based flutist and musicologist, and is digital media editor at The WholeNote. She can be reached at editorial@thewholenote.com. 66 | November 1, 2016 - December 7, 2016 thewholenote.com

DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS REVIEWED I don’t quite know where to begin. I can only imagine Bruce Surtees’ feelings over the past month as he approached the formidable task of assessing the 200 discs and wealth of literature in the Mozart 225 set. And then to realize that he also immersed himself in the complete symphonies and concertos of Shostakovich… the mind just boggles. But it did give me a good excuse to hold back a disc that I would normally have sent to him: Shostakovich – Cello Concertos 1 + 2 featuring Alisa Weilerstein and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks under Pablo Heras-Casado (Decca 483 0835). “A young cellist whose emotionally resonant performances of both traditional and contemporary music have earned her international recognition…Weilerstein is a consummate performer, combining technical precision with impassioned musicianship.” So stated the MacArthur Foundation when awarding Weilerstein a 2011 MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship. With four previous Decca titles (ranging from solo suites by Kodály and Golijov to concertos of Dvořák, Elgar and Carter) and a host of collaborative recordings to her credit, Weilerstein maintains the high bar she has set for herself by tackling two of the most iconic works in the 20th-century canon. It must have been a daunting undertaking, especially considering that both concertos were written for that towering figure Mstislav Rostropovich. However, as was the case of the Carter concerto where she had the privilege of working with the 103-year-old composer prior to her recording, we are told in the liner notes that Weilerstein had the opportunity to gain some firsthand knowledge from the dedicatee. “I played the First for Rostropovich when I was 22. He was a titanic presence, sitting very close, his feet almost touching mine. I played the entire concerto for him without stopping. He then gave me a piece of advice that I will never forget: he said that the emotions that the performer conveys while playing Shostakovich’s music should never be ‘direct’ or ‘heart on sleeve’ in a Romantic sense. That is not to say that the music is unemotional, but rather that it presents a unique challenge to the performer, who must convey a kind of duality – conveying intense emotion that has somehow to be concealed at the same time.” Now, a dozen years later, I would say that Weilerstein has accomplished just that. Of course this new release drove me back to my archives to find the recordings I cut my teeth on, Rostropovich with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra (No.1) and with Ozawa and the Boston Symphony (No.2) – thank goodness my vinyl collection is still intact – and I was struck by two things. First was just how good the DG LP with Ozawa recorded in 1967 still sounded (clicks and pops notwithstanding) – especially the explosive power of the big bass drum DAVID OLDS punctuating the extended cello cadenza of the opening Largo and the clarity of the contrabassoon lines. The second was how well Weilerstein’s performances stood up to the comparison. In my mind’s ear Rostropovich had a god-like power and intensity beside which I thought any mere mortal would pale. But Weilerstein’s command of her instrument, and her understanding of the music as detailed in her insightful comments in the notes, prove her more than equal to the task. (Of course I will not be trading in my vinyl anytime soon.) The recordings took place in the Herkulessaal in Munich in September 2015 and are both impeccable. The First was captured in a closed session under studio conditions while the Second was recorded during a concert later the same week. Try as I might I can’t hear any evidence of the audience, but there is certainly the dynamic sense of excitement of a live performance. I’m very happy to add this new offering to my collection. The next disc provided a very different listening experience. Roma Aeterna – Rome the Eternal City – features the outstanding vocal quartet New York Polyphony in works by Palestrina and Victoria (BIS 2203 SACD). The first thing that struck me was the gorgeous acoustic space of the recording, gloriously captured by engineer Jens Braun in Omaha’s St. Cecilia Cathedral in August 2015. The core members of the group – Geoffrey Williams, countertenor; Steven Caldicott Wilson, tenor; Christopher Dylan Herbert, baritone; and Craig Phillips, bass – are joined by countertenor Tim Keeler, tenor Andrew Fuchs and bass-baritone Jonathan Woody as required by the repertoire which ranges from four to six voice settings. But it is hard to realize that all this glorious sound is emanating from such small ensembles. The one voice per part does assure clarity however, complemented by precise diction and impeccable intonation. Part of this clarity is actually built into the compositions. In Ivan Moody’s excellent program notes we are told that Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli for six voices was for a time thought to have been written around 1565 in response to the injunctions of the Council of Trent (1562), which stipulated that music must allow the texts of the Mass and Offices to be heard as clearly as possible. This mass was even believed by some – Agostino Agazzari is cited – as having singlehandedly saved ecclesiastical polyphony from being banned in the wake of the changes brought about by the Counter-Reformation. The notes go on to say however that it may have been composed as early as 1555, independent of the edicts, to celebrate the election of Pope Marcellus II. Be that as it may, Missa Papae Marcelli does exemplify the concerns 6200 RECORDINGS REVIEWED. AND COUNTING. Support local music. Support The WholeNote. Visit www.patreon.com/thewholenote thewholenote.com November 1, 2016 - December 7, 2016 | 67

- Page 1 and 2:

VISIT WWW.PATREON.COM/THEWHOLENOTE

- Page 3 and 4:

KOERNER HALL IS: “ A beautiful sp

- Page 5 and 6:

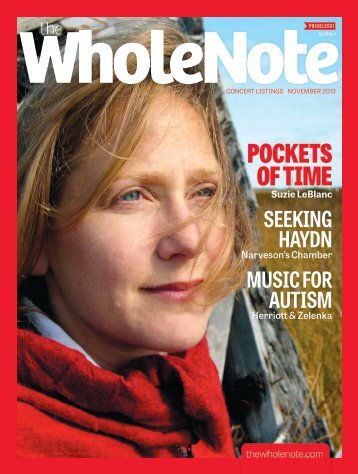

Volume 22 No 3 | November 2016 FEAT

- Page 7 and 8:

Errors in Print Speaking of eagle-e

- Page 9 and 10:

Quatuor Arthur-LeBlanc great chambe

- Page 11 and 12:

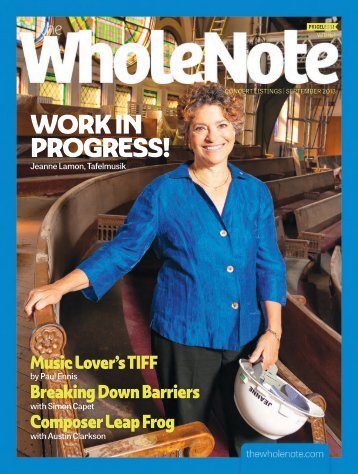

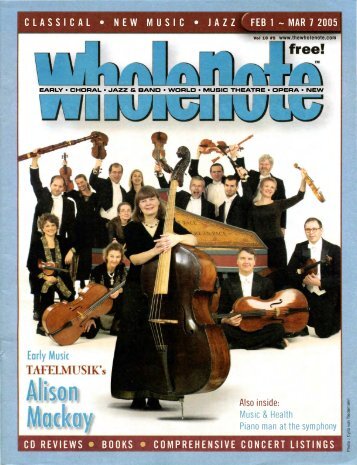

and Tafelmusik’s ongoing relation

- Page 13 and 14:

thewholenote.com November 1, 2016

- Page 15 and 16: Beat by Beat | Classical & Beyond S

- Page 17 and 18: prominent use of the organ. The Kli

- Page 19 and 20: Edmonton and Winnipeg Symphony Orch

- Page 21 and 22: from Denmark, Italy, Slovenia, Japa

- Page 23 and 24: Kingston Symphony Orchestra music d

- Page 25 and 26: C H O R A L E C H O R L A E BACH CH

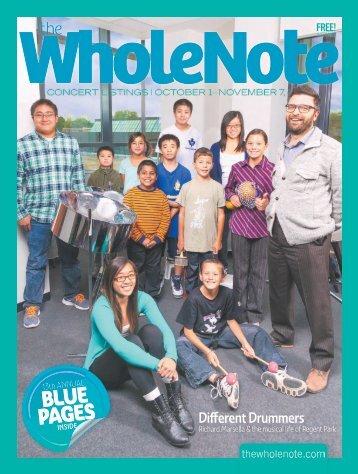

- Page 27 and 28: Nagata Shachu and Ten Ten: Toronto

- Page 29 and 30: concert is a great chance to hear s

- Page 31 and 32: choreographs the piece. The second

- Page 33 and 34: Villa-Lobos’ Cançao do Poeta do

- Page 35 and 36: are now performing quite regularly.

- Page 37 and 38: LISTINGS The WholeNote listings are

- Page 39 and 40: Elijah at Koerner Hall November 5,

- Page 41 and 42: Generation Next Charles Richard-Ham

- Page 43 and 44: 905-615-4830. PWYC (suggested donat

- Page 45 and 46: APOLLO & DAPHNE By Handel desire &

- Page 47 and 48: Music. Jazz Festival: Jazz Vocal En

- Page 49 and 50: Rachmaninoff. Gordon Murray, piano.

- Page 51 and 52: Music. Wind Symphony. Applebaum: Th

- Page 53 and 54: on ‘Kling no, klokka’. Andrew A

- Page 55 and 56: four violins; Mendelssohn: String O

- Page 57 and 58: ●●12:30: Don Wright Faculty of

- Page 59 and 60: Beat by Beat | Mainly Clubs, Mostly

- Page 61 and 62: November 1 David Hollingshead. Nove

- Page 63 and 64: WholeNote CLASSIFIEDS can help you

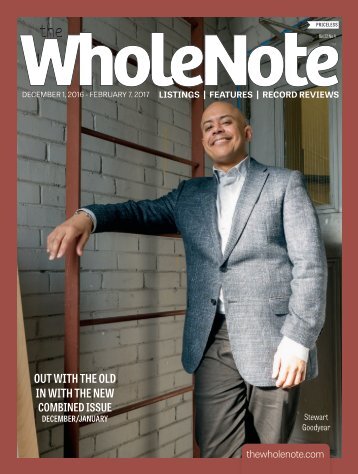

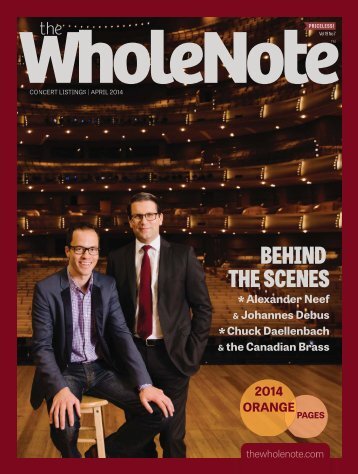

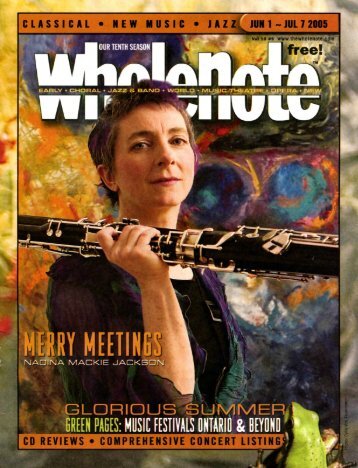

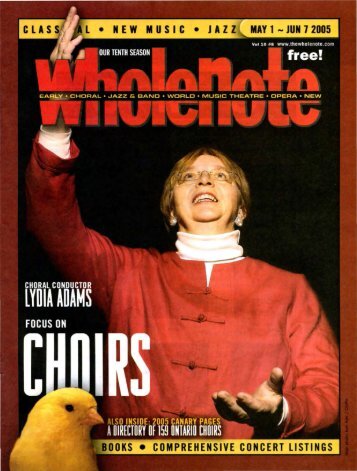

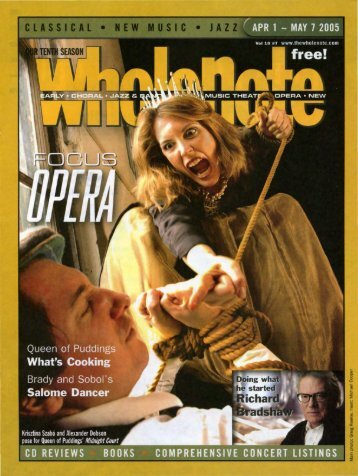

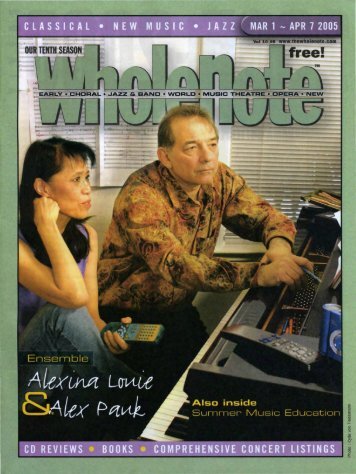

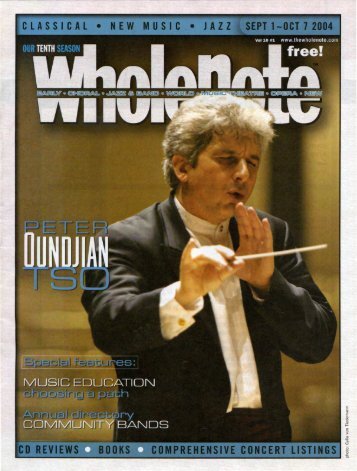

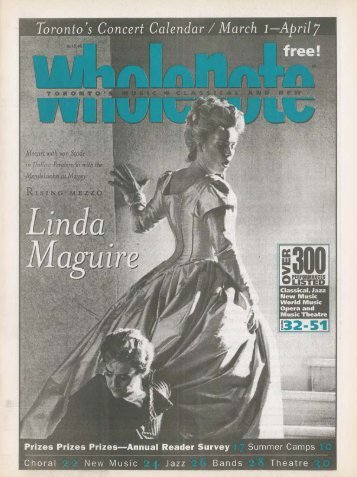

- Page 65: NEW CONTEST ! Who is December’s C

- Page 69 and 70: If you missed this set the first ti

- Page 71 and 72: Wenceslaus Church on November 23. L

- Page 73 and 74: y Lust and by Virtue. Forced to mak

- Page 75 and 76: makes this DVD from Barcelona’s L

- Page 77 and 78: Gergiev was immobilized after the m

- Page 79 and 80: JAZZ AND IMPROVISED Accomplice Amy

- Page 81 and 82: a myriad of traditional, experiment

- Page 83 and 84: Ice and Longboats: Ancient Music of

- Page 85 and 86: Old Wine, New Bottles | Fine Old Re

- Page 87 and 88: Drawings such as these from Thoreau

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...