Volume 24 Issue 1 - September 2018

- Text

- September

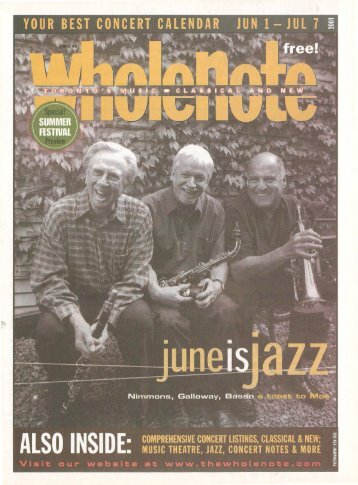

- Jazz

- Toronto

- Musical

- Symphony

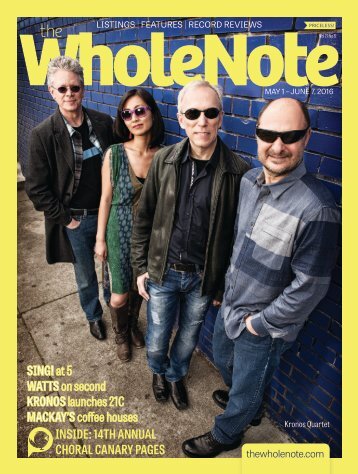

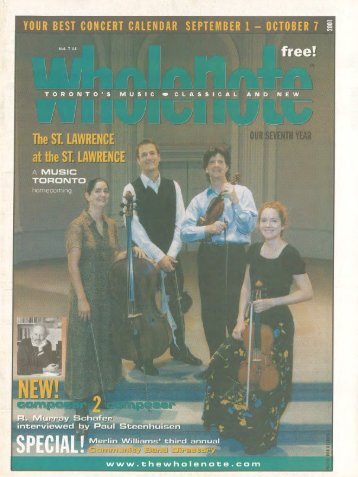

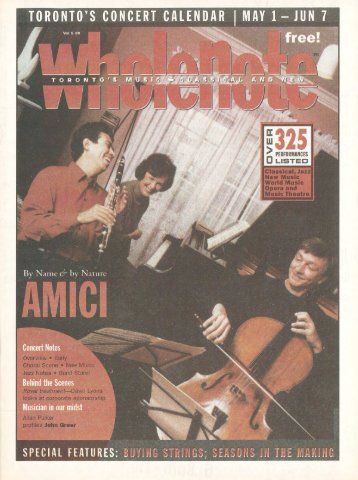

- Quartet

- Orchestra

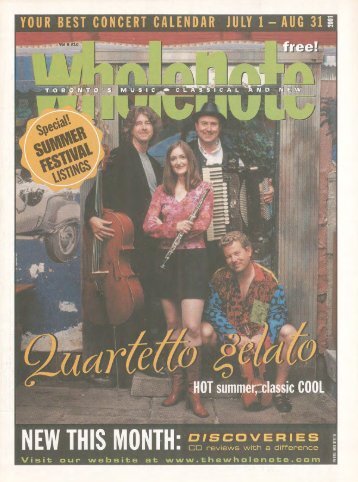

- Festival

- Theatre

- Violin

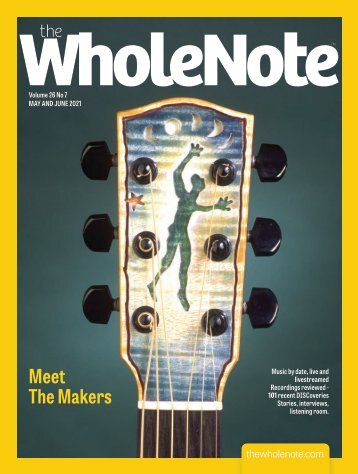

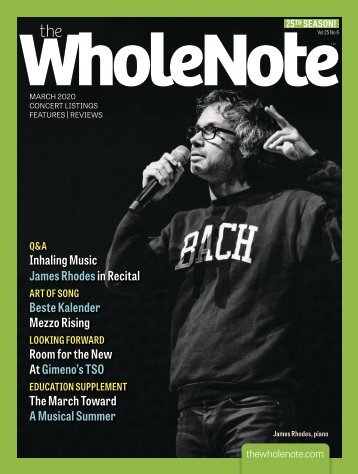

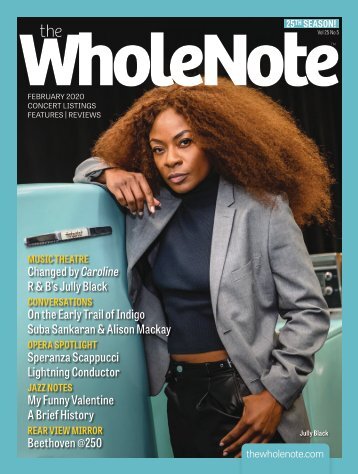

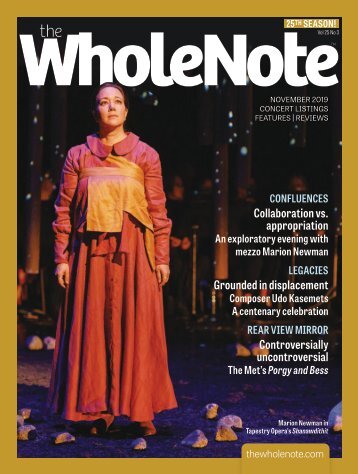

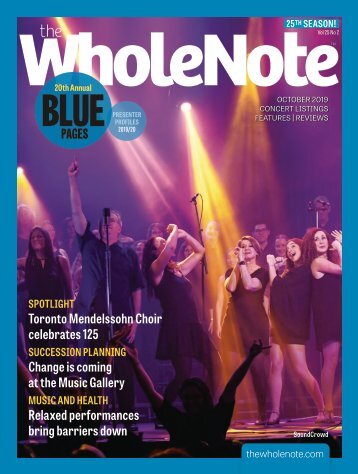

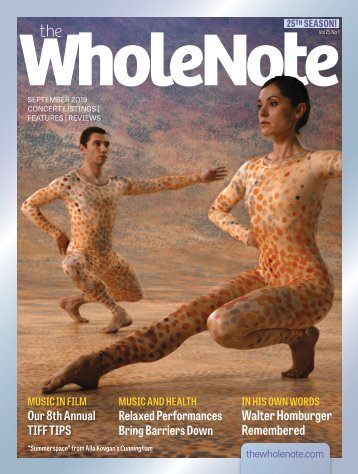

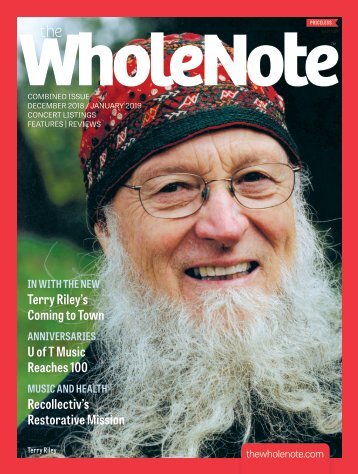

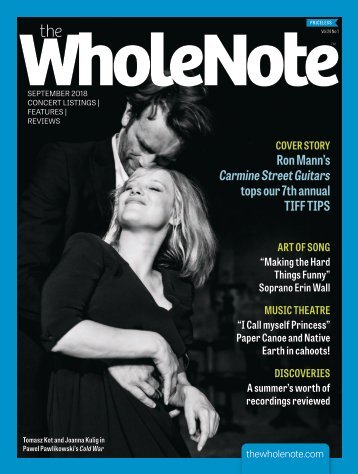

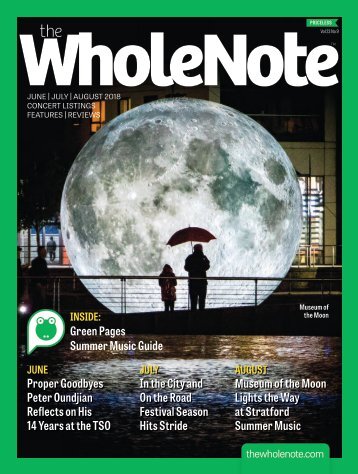

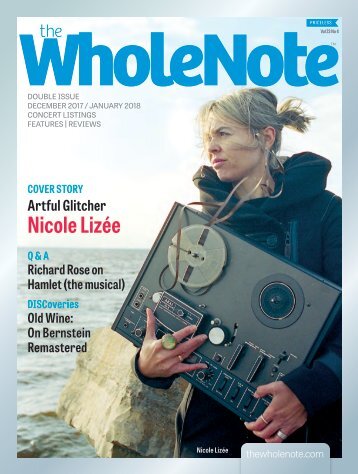

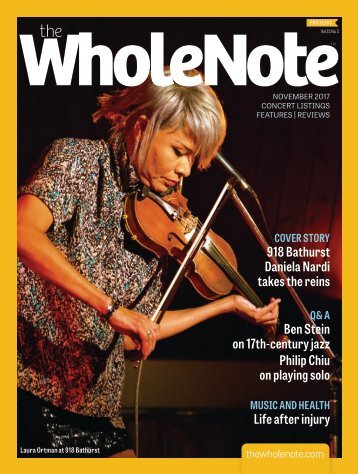

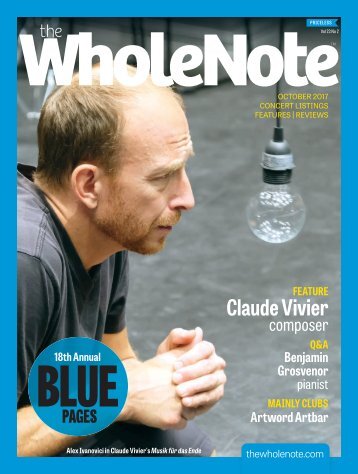

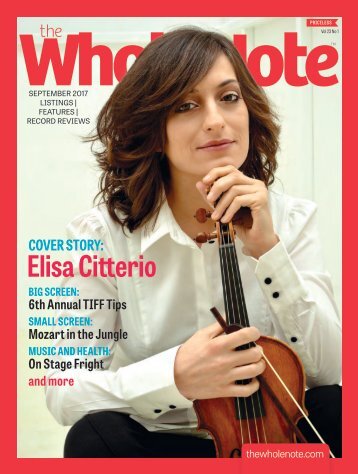

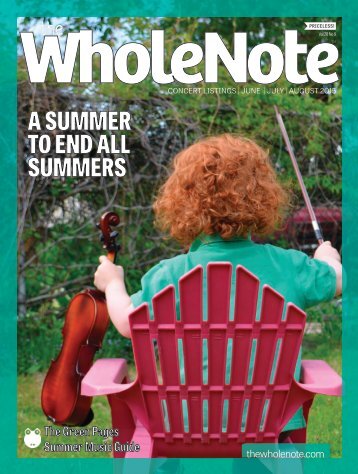

In this issue: The WholeNote's 7th Annual TIFF TIPS guide to festival films with musical clout; soprano Erin Wall in conversation with Art of Song columnist Lydia Perovic, about more than the art of song; a summer's worth of recordings reviewed; Toronto Chamber Choir at 50 (is a few close friends all it takes?); and much more, as the 2018/19 season gets under way.

RAMONA TIMAR Beat by

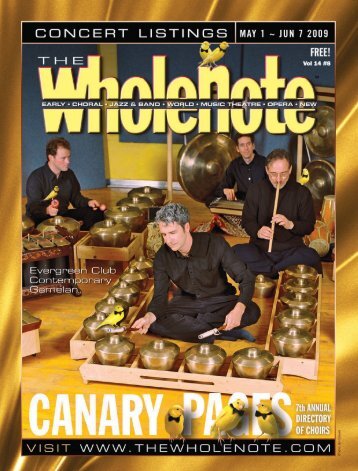

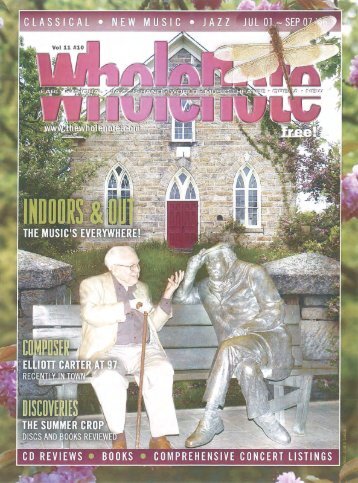

RAMONA TIMAR Beat by Beat | World View Rebooting the Beat: Thoughts on the “World Music” Tag ANDREW TIMAR Just past mid-August my WholeNote editor called. Fall on the doorstep, it was time to fine-tune stories for my September column. “What do you have?” he asked. “I am wondering if it’s time for a terminology reboot” I replied. (My column has been called “World View” and the beat I cover has been described as “world music” for a decade or more, even before I took over from my pioneering predecessor columnist Karen Ages.) What got me thinking about all this is that I’d been busy all summer attending, playing in and following online stories of festivals which could be tagged with the “world music” moniker. To begin with, in June I toured with Toronto’s Evergreen Club Contemporary Gamelan (ECCG) representing Canada at the International Gamelan Music Festival in Munich, Germany. Cheekily dubbed “Indonesia # Bronze.Bamboo.Beats,” the experience proved both exhilarating and exhausting. For ten days the Munich Municipal Museum hosted for the first time what turned out to be Europe’s largest gamelan festival. There was a two-day symposium, over 300 participants giving 40 concerts and 28 workshops at six venues, in an environment that was much more about a global community sharing a passion for music rather than a commercial enterprise. Not a single band was selling an album or T-shirt. On public display all over downtown Munich was the face of the transnational contemporary gamelan music scene. Far from its birthplace on the islands of Java and Bali in Indonesia, European audiences witnessed live performances of gamelan music which had been adopted and adapted by people all over the globe. What was emotionally and artistically powerful to hear was how some of those diasporic musical adaptations and personalizations (including those by 35-yearglobal-gamelan-scene veterans ECCG - Canadians who are musically rather than ethnically connected to Indonesian culture) have been in turn absorbed and indigenized by Indonesian innovators. It was in turns unexpected and inspiring to personally experience all this in the Bavarian home of Oktoberfest. Is this one face of “world music” in practice today? Then on the August 17 weekend I attended the Small World Music Festival (SWMF) at Harbourfront Centre. This year it celebrated the 30th anniversary of the first North American WOMAD (World of Music Art and Dance) which took place at the same venue. WOMAD, Evergreen Club Gamelan performing on the Anne Tindall stage at the first Toronto WOMAD, August 14, 1988. “the world’s most influential global music event … became a landmark event during its [five-year] tenure at Harbourfront,” according to Small World. “The ear-opening inspiration it provided led directly to the formation of Small World Music. Three decades on, we explore this legacy and how it resonates in multicultural 21st-century Toronto.” I had not only visited WOMAD during its landmark first year here but had also helped arrange an Evergreen Club Gamelan concert on August 14, 1988 and then played in it. So at some level my interest in this year’s SWMF was personal. Keen to get beyond the autobiographical, though, I checked out two SWMF panels and a workshop, on the afternoon of August 18, 2018. The “WOMAD 30” panel, made up of people who were involved in it on various levels, looked back at that first 1988 music festival that in the words of its Facebook events page, “changed the perception of music in Toronto.” Moreover, in terms of live music, it introduced the “world music” brand, then barely one year old, imported from the UK to Canada. The second panel “A Post-Genre World” asked some big questions: How do artists, audiences and industry work together in the post-genre world? How are livelihoods and bottom lines affected by a multi-fractured or multi-faceted music space? How does genre affect the creative process?” I found the answers offered in both panels memory-jogging, thought-provoking and compelling. World Music: the double birth of a term I’ve weighed in on various occasions in this column on the notion of world music, its promoters, detractors, its problems and its origins. It’s helpful to keep in mind that the term “world music” entered the musical lexicon on two separate occasions, on two continents, serving two quite different purposes and masters. Its academic origins appeared around 1962, coined and promoted by American ethnomusicologist Robert Brown, professor at Wesleyan University. He meant it as an inclusive term to be used in university music education to describe “living music” and to be used to “foster awareness and understanding of the world’s performing arts and cultural traditions through programs of performance and teaching.” That once-academic term got a marketing refresh a quarter century later, however, at a June 1987 gathering of record label bosses, retailers and producers in the Empress of Russia, a nowdefunct London pub. Why was a new marketing tag so necessary that these thirsty English professionals had to put their pints down? In a succinct 2011 story in The Guardian, journalist Caspar Llewellyn Smith reported that “Charlie Gillett who was present that evening, recalled one example of the problem at hand: in the US, Nigeria’s King Sunny Ade would be filed under reggae, while in the UK, he ‘was just lost in the alphabet, next to ABBA.’ After several proposed terms were vetted, ‘world music’ stuck and ‘11 indie labels put in £3,500 between them to introduce newly labelled sections in record stores.’” At its commercial birth, “world music” was all about labelling, increasing album visibility, genre identity, market share - and thus hopefully sales - in international brick and mortar record stores. (It doesn’t take a Cassandra to observe that it’s a very different world in 2018, when there are many fewer physical shops and when some musicians and presenters increasingly embrace the possibility of a post-genre musical future.) 36 | September 2018 thewholenote.com

Genre vs post-genre: late 20th century record store racks Back in the last two decades of the 20th century, genre still proudly ruled Toronto’s imposing multi-department, multi-floor record (and then also cassette tape) shops. Following London’s lead, there was a wholesale switchover for many records to the World Music label from what previously were marked Folk or International record shelves. I well recall schlepping numerous times up the creaky upper level wooden stairs of Sam the Record Man’s flagship Yonge St. store to its upper floors. My mission as Evergreen Club Gamelan’s artistic director and Arjuna label manager was to chart the (to be frank, modest) sales of our LP North of Java (1987). I did the same for its CD remix namesake when it was released in 1992, making sure it wasn’t buried too deeply on the shelf. What was on that album? All the compositions were by youngergeneration Canadian composers. All the musicians were Canadian, it was recorded in a Scarborough, Ontario studio, and the label was registered in Ontario by ECG. While gamelan degung instruments were featured on most cuts, some made prominent use of decidedly non-gamelan sound sources like a synthesizer, electric bass and field recordings, as in the case of my work North of Java. Nevertheless, Sam’s didn’t rack it in the substantial Classical Canadian section on the first floor. Now I understand the album was a novelty, being the first Canadian gamelan disc. But this (to my mind) quintessential Canadian album in that retail environment was displayed not with Canadian music, but in the World Music section among other albums with which it had little in common, a long, long walk up. World music: contesting and defending the term My North of Java album story reveals the difficulties retailers faced when attempting to apply the new world music marketing tool. In that case it was misinterpreting a product with multiple layers of cultural and music genre affiliation, racking it by default, I assume, in the World Music section. The commercial use of world music on one hand fuelled consumer interest in sounds from outside the Western mainstream both on recordings and in live concerts, yet on the other hand it posed the risk of ghettoization, of “othering,” the world’s myriad individual music traditions. Such risks have been articulated in recent decades by numerous voices raised in consternation over the term, seeing it as a polarizing factor. Rock star David Byrne, an early world music adopter, was also thereafter an early dissenter. In his strongly worded October 1999 New York Times article provocatively titled Why I Hate World Music, he sums up some of the problems he saw in the way it had been commercially applied and then received by consumers: “In my experience, the use of the term world music is a way of dismissing artists or their music as irrelevant to one’s own life ... It’s a way of relegating this ‘thing’ into the realm of something exotic and therefore cute, weird but safe, because exotica is beautiful but irrelevant … It groups everything and anything that isn’t ‘us’ into ‘them.’ This grouping is a convenient way of not seeing a band or artist as a creative individual … It’s a label for anything at all that is not sung in English or anything that doesn’t fit into the Anglo-Western pop universe this year.” Many in the business took notice of Byrne’s passionate denunciation. The following March, Ian Anderson, musician, broadcaster and the editor of fRoots published a lengthy rebuttal in his magazine. In it, he explored many crannies of the topic, including the different resonances world music had in America, UK, France, and among African musicians and audiences. He summed up with, “It’s not all positive, but World Music (or Musique du Monde in neighbourly Paris) is way ahead on points. It sells large quantities of records that you couldn’t find for love or money two decades ago. It has let many musicians in quite poor countries get new respect (and houses, cars and food for their families), and it turns out massive audiences for festivals and concerts. It has greatly helped international understanding and provoked cultural exchanges. …I call it a Good Thing…” Pierre Kwenders, the early-career Congolese-Canadian singer and rapper is not impressed with arguments for the term’s usefulness. Shortlisted for the 2015 JUNO Award for World Music Album of the Year and the September 2018 Polaris Prize, Kwenders called out the Pierre Kwenders marketing term on the CBC show q on August 24, 2018. His point comes close to the one I made in the case of North of Java. “What is world music? What is that ‘world’ we put in that box? It’s ridiculous [for example] that classical music from India is put in the same category as the music I make … it doesn’t make any sense. I believe I’m making pop music and it should be put in the pop music category.” Despite all these concerns, there is still a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album today. Ladysmith Black Mambazo won it earlier this year. Moreover the terms world fusion, ethnocultural music, worldbeat and roots music have been touted as less controversial alternatives, but with modest commercial or popular traction. As I wrote at the outset of this article, this column has been called “World View” and this beat has been described as “World Music” for over a decade. Is it time for a change? I, and my editor, welcome your comments. Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com. thewholenote.com September 2018 | 37

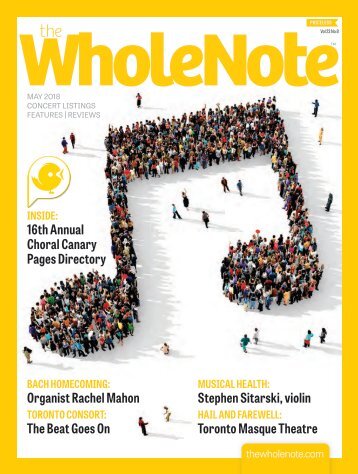

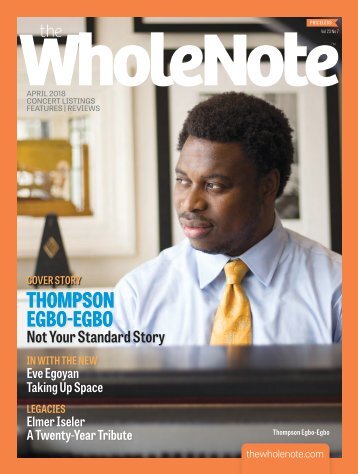

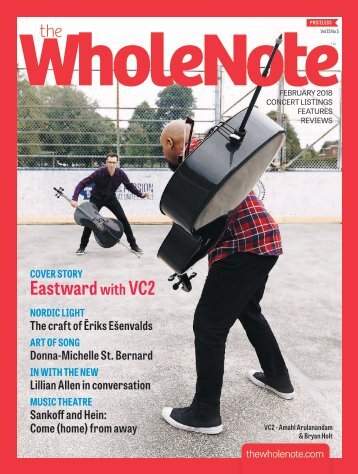

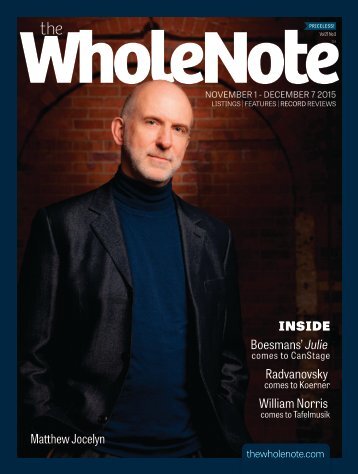

- Page 1 and 2: PRICELESS Vol 24 No 1 SEPTEMBER 201

- Page 3 and 4: 2018/19 Season Mozart’s evocative

- Page 5 and 6: 2401_Cover.indd 1 PRICELESS Vol 24

- Page 7 and 8: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Instrum

- Page 9 and 10: GREAT CHAMBER MUSIC DOWNTOWN STRING

- Page 11 and 12: AGA KHAN MUSEUM PERFORMING ARTS PRE

- Page 13 and 14: Falls Around Her Now in its 24th se

- Page 15 and 16: enabled me to begin my work develop

- Page 17 and 18: FEATURE ART OF SONG Soprano Erin Wa

- Page 19 and 20: It’s what got me through December

- Page 21 and 22: An agency of the Government of Onta

- Page 23 and 24: From the brutality of the Janáček

- Page 25 and 26: SIMON FRYER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 2018

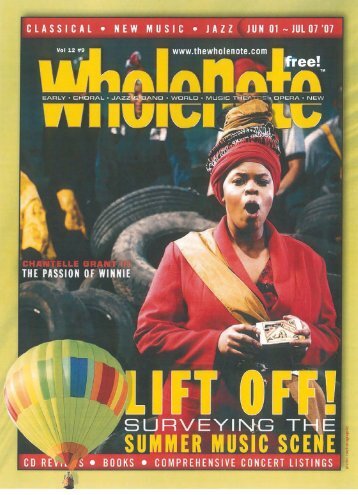

- Page 27 and 28: year, and was soon joined by Charlo

- Page 29 and 30: Season Sponsors Cidel Asset Managem

- Page 31 and 32: MATTHEW WELCH Rufus Wainwright, com

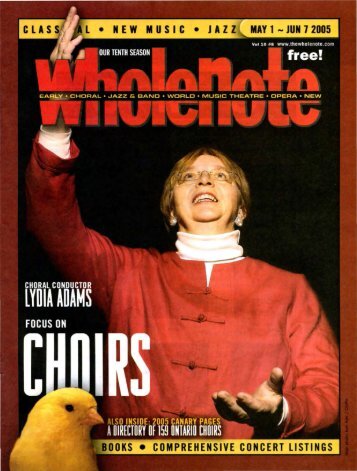

- Page 33 and 34: Beat by Beat | Choral Scene First S

- Page 35: Fifty years ago, all it took was a

- Page 39 and 40: EVA KAPANADZE Harrison Argatoff com

- Page 42 and 43: The WholeNote listings are arranged

- Page 44 and 45: Hall, 60 Simcoe St. 416-598-3375. $

- Page 46 and 47: ●●8:00: Music Toronto. Marc-And

- Page 48 and 49: event. Kati Gleiser, piano. Harmony

- Page 50 and 51: JAZZ/BLUES/STREET ART Beat by Beat

- Page 52 and 53: mezzettarestaurant.com (full schedu

- Page 54 and 55: Classified Advertising | classad@th

- Page 56 and 57: DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS REVIEWED D

- Page 58 and 59: STRINGS ATTACHED TERRY ROBBINS What

- Page 60 and 61: Chrysostom Church in Newmarket. Vol

- Page 62 and 63: Concerto into a private and intimat

- Page 64 and 65: CLASSICAL AND BEYOND Lachrimae John

- Page 66 and 67: MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY Korngold -

- Page 68 and 69: influence of the advanced early 20t

- Page 70 and 71: The performances of bassist George

- Page 72 and 73: is evoked through barely moving tex

- Page 74 and 75: part of the heritage of New Orleans

- Page 76 and 77: REMEMBERING Celebrating the Life of

- Page 78: Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...