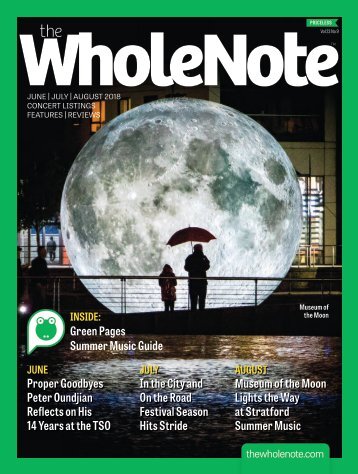

Volume 25 Issue 5 - February 2020

- Text

- Composer

- Performing

- Orchestra

- Arts

- Theatre

- Musical

- Symphony

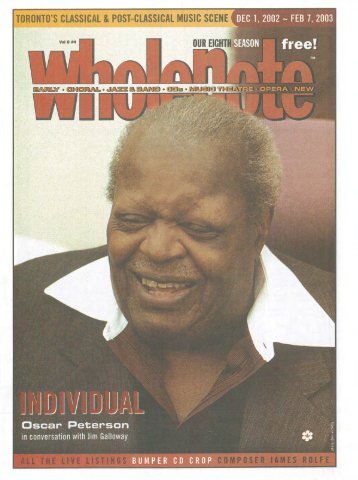

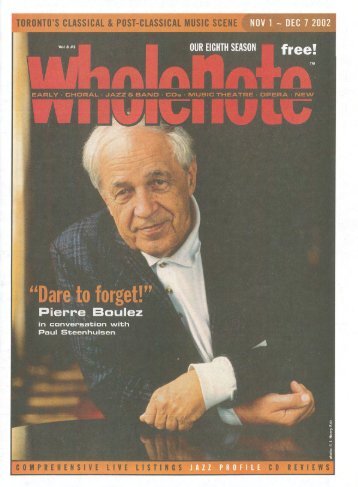

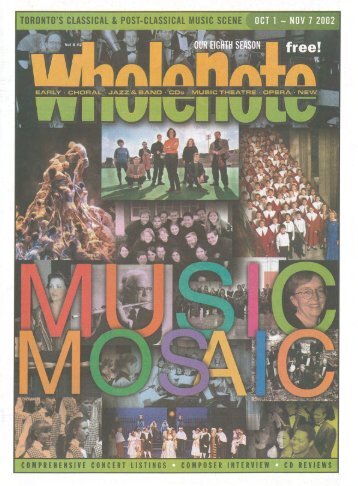

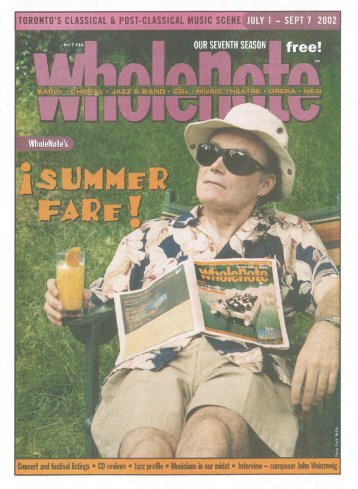

- Jazz

- Toronto

- February

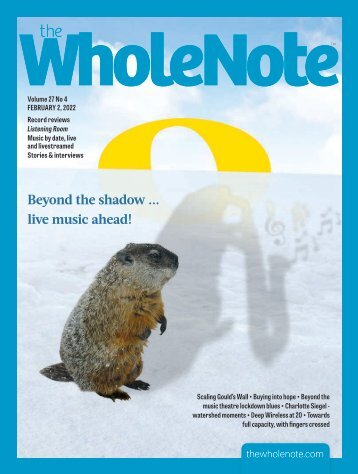

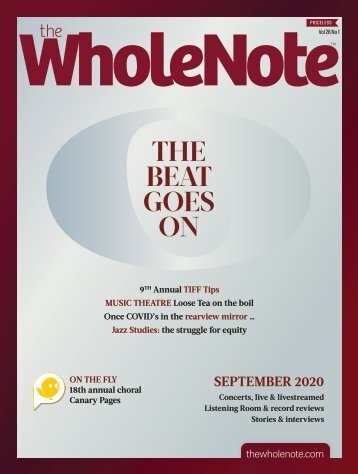

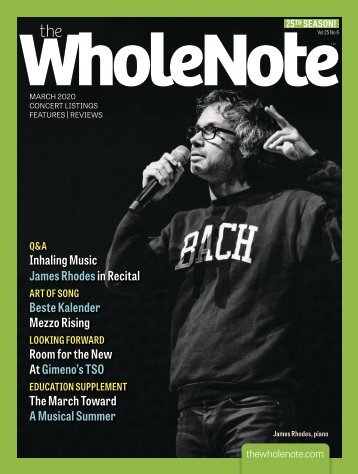

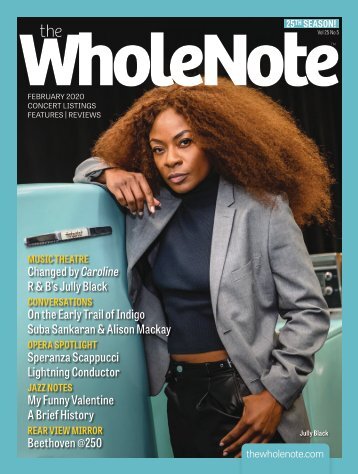

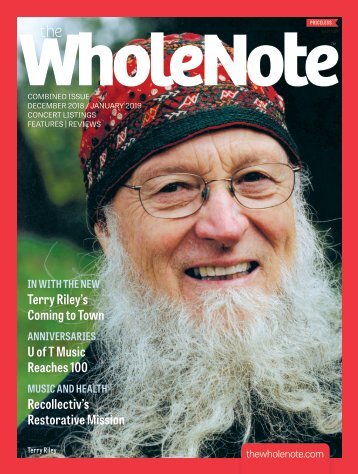

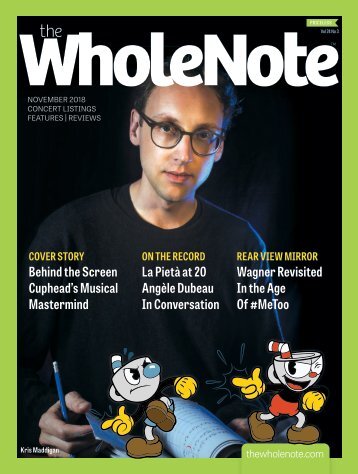

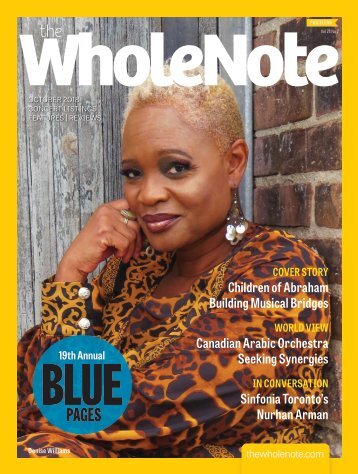

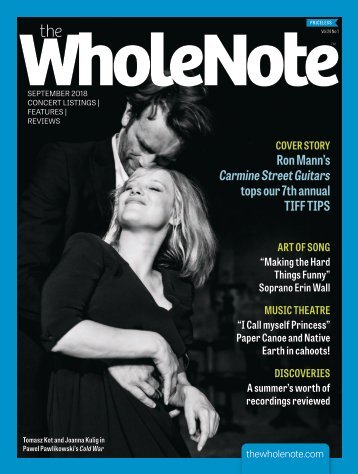

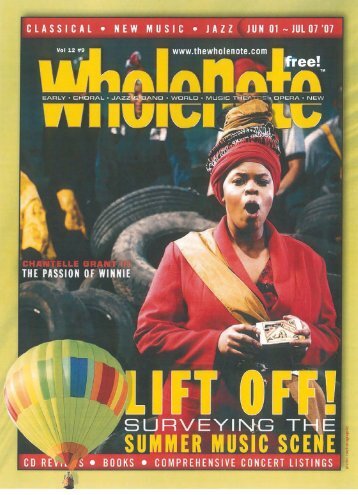

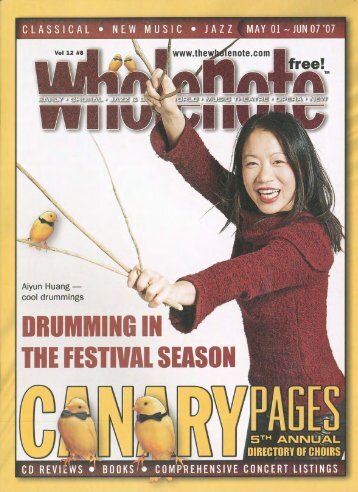

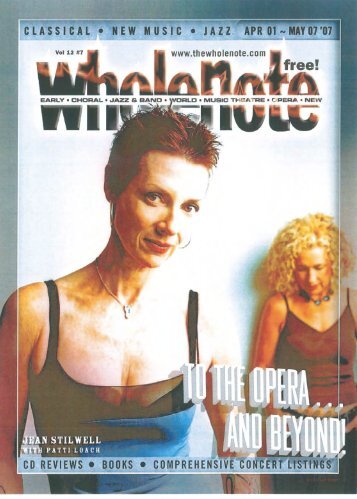

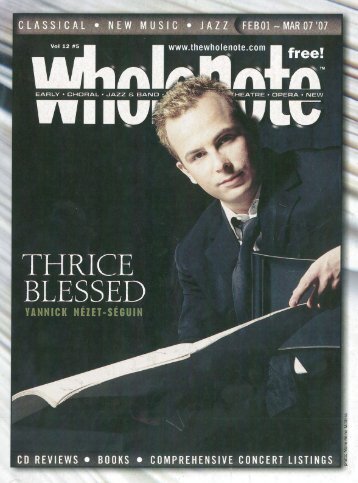

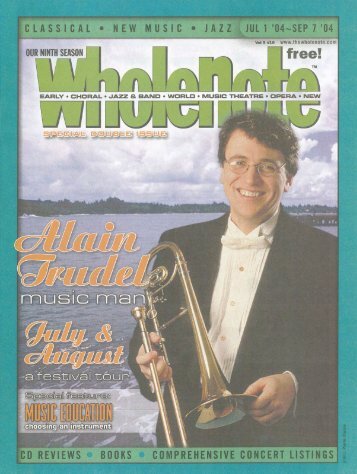

Visions of 2020! Sampling from back to front for a change: in Rearview Mirror, Robert Harris on the Beethoven he loves (and loves to hate!); Errol Gay, a most musical life remembered; Luna Pearl Woolf in focus in recordings editor David Olds' "Editor's Corner" and in Jenny Parr's preview of "Jacqueline"; Speranza Scappucci explains how not to reinvent Rossini; The Indigo Project, where "each piece of cloth tells a story"; and, leading it all off, Jully Black makes a giant leap in "Caroline, or Change." And as always, much more. Now online in flip-through format here and on stands starting Thurs Jan 30.

The insightful booklet

The insightful booklet notes by violist John Largess add another touch of class to a quite outstanding issue. The Dover Quartet swept the board at the 2013 Banff International String Quartet Competition, winning every available prize, and if you needed any proof of their continuing rise to the very top of their field then their latest CD The Schumann Quartets (Azica ACD-71331 naxosdirect.com) should more than suffice. Schumann wrote his three Op.41 string quartets – No.1 in A Minor, No.2 in F Major and No.3 in A Major – in a six-week period in 1842, never to return to the genre. They are quite lovely works, richly inventive and with more than a hint of Mendelssohn, to whom they were dedicated. The Dover Quartet gives immensely satisfying performances of these brilliant works on a generous CD that runs to almost 80 minutes. The latest CD from the always-interesting Rachel Barton Pine – Dvořák Khachaturian Violin Concertos with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra under Teddy Abrams (Avie AV2411 naxosdirect.com) – is apparently not what it was meant to be, the originally planned “very different” album having to be changed at the last minute when the conductor became unavailable. These two concertos immediately struck the soloist as an attractive alternate project: she learned both works at 15 and had played each of them a few times during the previous concert season. Tied as they are by each composer’s use of his own ethnic music they do make a good pair, but although there’s much fine playing here it feels somewhat subdued at times and never quite seems to really hit the heights the way you would expect, possibly due to the last-minute nature of the recording session but also possibly because Barton Pine seems to take a more lyrical approach to works that are strongly rhythmic as well as strongly melodic. The Khachaturian fares better in this respect, with a particularly fiery cadenza from the soloist. Perspectives is a fascinating CD by violinist Dawn Wohn and pianist Esther Park that explores the differing cultures and perspectives of women composers, reaching back to the 19th century and into the 21st (Delos DE 3547 naxos.com) The nine works are: Jhula-Jhule by Reena Esmail (b.1983); Episodes by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (b.1939); the particularly lovely Legenda by the Czech composer Vítěslava Kaprálová, who died at only 25 in 1940; Star-Crossed (commissioned for the CD) by Jung Sun Kang (b.1983); the remarkable solo violin piece, Proviantia “Sunset of Chihkan Tower,” by Chihchun Chi-sun Lee (b.1970); Deserted Garden and Elfentanz by Florence Price (1887-1953); the lovely Nocturne by Lili Boulanger (1893-1918); Portal by Vivian Fine (1913-2000); and Romance by Amy Beach (1867-1944). Wohn plays with warmth, a crystal-clear tone and a fine sense of line and phrase in an immensely satisfying recital, with equally fine playing from her musical partner Park. The outstanding cellist Daniel Müller-Schott is back with #CelloUnlimited, an impressive recital of 20th-century works for solo cello (ORFEO C 984 191 naxosdirect.com). A passionate reading of the monumental and challenging Sonata Op.8 from 1915 by Zoltán Kodály makes a fine opening to the disc. Prokofiev’s Sonata in C-sharp Minor Op.134 from 1953, the year of his death, is really only based on a fragment of the first of four projected movements; using a contrasting theme apparently partly sourced from Mstislav Rostropovich it was made into a performing version by the composer and musicologist Vladimir Blok in 1972. Hindemith’s Sonata Op.25 No.3 from 1922 and Henze’s 1949 Serenade both consist of short but effective movements – nine each less than one minute long in the latter. Müller-Schott’s own Cadenza from 2018 is followed by the early and surprisingly tonal 1955 Sonata by George Crumb; and Pablo Casals’ brief Song of the Birds, with which he always used to end his concerts, provides a calm and peaceful ending to a solo CD full of depth and fire. It’s not unusual to encounter performances of both the Bach Sonatas & Partitas for solo violin and the solo Cello Suites in transcription: viola players, for instance, have available arrangements of both, and the Cello Suites can be found transcribed for violin. Less common, though, are performances of the violin Sonatas & Partitas on cello, but this is what Mario Brunello provides on Johann Sebastian Bach Sonatas & Partitas for solo violoncello piccolo (ARCAN A469 naxosdirect.com). Brunello says that he tried playing the works on a four-string (not the usual five-string) smaller violoncello piccolo with no particular intention, and found that with the smaller body and the same tuning as a violin (but an octave lower) in effect the instrument felt like a larger or tenor violin, allowing him to read the Sonatas & Partitas as a cellist without having to resort to near-impossible technical virtuosity. He also points out that the natural tendency for a cellist to first apply the bow to the lowest string leads to what he calls a “lookingglass” reading and a “seen from the bass line” approach in his playing, the instrument’s resonant body encouraging lingering on the low notes. Brunello certainly does that, even in the dance movements, but although it occasionally threatens to compromise the pulse it never really feels like more than just taking a breath and not rushing. The instrument he plays is a 2017 model by Filippo Fasser of Brescia, after Antonio and Girolamo Amati of Cremona, 1600-1610. The pitch employed is a’ = 415 Hz, so down a semi-tone from the printed violin score. It all works really well, although obviously the trade-off is that the brightness of the violin is lost, especially with the octave drop. There’s an interesting effect in the Andante of the A minor Sonata No.2, where Brunello plays the first half of the movement pizzicato and then changes to arco for the repeat, reversing the pattern for the second half. There’s a fine resonance to the recording, and Brunello’s playing is admirable. There’s another cello arrangement of a well-known violin work on Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, an arrangement for cello and string ensemble by cellist Luka Šulić, who is accompanied by the Archi dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia (Sony Classical 19075986552 sonymusicmasterworks.com). This also seems to work very well, giving the music a slightly darker tinge than usual, although with the lower register the solo line is difficult to distinguish in places. When it’s clearly audible it’s really impressive playing, with Šulić displaying terrific facility and agility and handling the intricate solo line with apparent ease. Full-blooded and committed ensemble playing, especially in the Allegro and Presto movements, where tempos are never on the slower side, makes for a really enjoyable CD. We still tend to think of Andrés Segovia as being the guitarist most responsible for establishing the classical guitar in the concert hall, so Fernando Sor The 19th-Century Guitar, a new CD from the Italian guitarist Gianluigi Giglio (SOMM SOMMCD 0604 64 | February 2020 thewholenote.com

somm-recordings.com) is an excellent reminder of similar efforts from 100 years earlier. As Michael Quinn points out in the booklet notes, the Spanish composer and guitarist was a pioneering advocate for the guitar as an instrument that belonged in the concert hall, building on the successes of Mauro Giuliani and Ferdinando Carulli in the first decade of the 1800s and producing the seminal Méthode pour la Guitare in 1830 along with a stream of compositions that extended both the instrument’s vocabulary and technique. The eight works featured here all date from the period 1822-1836, when Sor had returned to Paris after spending eight years in London. They include the Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart Op.9, the Easy Fantasy in A Minor Op.58, the Elegiac Fantasy in E Major Op.59 and the Capriccio in E Major, Le calme, Op.50. The Introduction and Variations on “Malbrough s’en va-t-en guerre” Op.28 – a tune better known now as “For he’s a jolly good fellow” – opens the disc, followed by Les folies d’Espagne and a Minuet Op.15a. Two movements from Mes Ennuis – Six Bagatelles Op.43 and the E Major No.23 from 24 Progressive Lessons for Beginners Op.31 complete the recital. Giglio plays with a full, warm and clean sound redolent of a modern classical instrument, but is in fact performing on a narrow-waisted but quite beautiful 1834 guitar by René Lacôte of Paris, illustrated in colour on the booklet front cover. Keyed In Domenico Scarlatti; Muzio Clementi – Keyboard Sonatas John McCabe Divine Art dda 21231 (divineartrecords.com) !! The erudite composer and pianist John McCabe left his mark on British musicmaking in the 20th century. His gifts as interpreter at the keyboard were very much equal to his abilities as composer. Discographic focus for the majority of his life centred upon neglected composers of old: Haydn, Clementi and Nielsen, among others. A recent reissue of two LPs that McCabe recorded in the early 1980s is a welcome one, pairing wellloved sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti with somewhat obscure works by the Italian-born English composer, pianist, pedagogue, conductor, music publisher, editor and piano manufacturer(!) Muzio Clementi. McCabe brings a muscular, cerebral approach to these pieces. One immediately detects a scrupulous composer behind the studio microphones, carefully etching formal structures for the benefit of the listener with accuracy and intellectual rigour. It is evident that McCabe delights in this piano music yet never indulges, electing for efficient lines and tasteful embellishment, reflective of both style and substance. Among the various highlights of Disc Two (Clementi) is the Sonata in G Minor, Op.50 No.3, subtitled “Didone Abbandonata” and composed in 1821. Expressive and probing, this music is liberated from the confines of continental neoclassicism, at once mournful and forlorn in prophetic anticipation of 19th-century music yet unwrit. From the last of his opuses for piano, Clementi marks the final movement of this sonata Allegro agitato e con disperazione. Such qualifiers were few and far between, even in 1821! Adam Sherkin Haydn Piano Sonatas Vol.2 John O’Conor Steinway & Sons 30110 (steinway.com) !! Celebrated for his characterful, refined interpretations of Beethoven, Schubert and – rather notably – John Ireland, Irish pianist John O’Conor has recently ventured into the 52 sonata-strong catalogue of Franz Joseph Haydn. The second in a projected series of such recordings with Steinway & Sons, this most recent release generally features late sonatas, varied in their formal structures yet irresistible in their innovations. O’Conor brings his customary warmth and tasteful approach to these classical essays: quirky, unexpected works at a good distance from the tautly balanced sonatas of Mozart and Schubert. Haydn’s experiments in the genre offer a wide spectrum of musical personality. They brush boisterously with folk idioms of the 18th century, skewing phrasing and lyrical gesture in a ribald quest of mirth and merriment. Their slightly roughand-tumble profile is not always captured by O’Conor. He appears to prize refined voicing and sculpted colour over a bit of pianistic fun. (Once in a while however, he does let himself loose amongst this music’s rustic urgings.) Despite the craft and polish, one detects a faint lack of familiarity with these works; figures and flourishes sound half-hearted, almost glossed over. It is in the slow movements on this record where O’Conor sounds most at home. He brings a sincerity to Haydn’s melodic lines born of an intimate, semplice mode of expression. O’Conor’s ear for colouristic subtlety delivers harmonic poise and vocal nuance, begetting interpretations that would surely have made the old Austrian composer smile. Adam Sherkin Beethoven – The Piano Concertos Ronald Brautigam; Die Kolner Akademie; Michael Alexander Willens BIS BIS-2274 SACD (bis.se) Beethoven – Piano Concertos 0-5 Mari Kodama; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Kent Nagano Berlin Classics 0301304BC (naxosdirect.com) ! ! The arrival of 2020 commences a year of celebration for classical music presenters and aficionados across the globe, who will celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth with innumerable concerts featuring the master’s greatest works. In advance of this significant anniversary, two recordings of Beethoven’s complete piano concertos were released late last year: one features the husband and wife duo of pianist Mari Kodama and conductor Kent Nagano; while the other presents fortepianist Ronald Brautigam, who is no stranger to Toronto, having performed with Tafelmusik at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre in 2010. Although these collections contain nearly identical musical contents (in addition to the standard five concertos, the Kodama/ Nagano release includes the Rondo in B-flat, Eroica Variations, Triple Concerto, and the reconstructed Piano Concerto “0”), the end thewholenote.com February 2020 | 65

- Page 1 and 2:

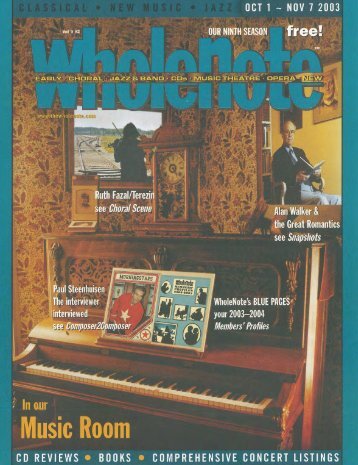

25 th SEASON! Vol 25 No 5 FEBRUARY

- Page 3 and 4:

2019/20 Season THE INDIGO PROJECT D

- Page 5 and 6:

2505_Feb2020_Cover.indd 1 2020-01-2

- Page 7 and 8:

FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Plenty

- Page 9 and 10:

BRIGHTEN YOUR FEBRUARY with BRILLIA

- Page 11 and 12:

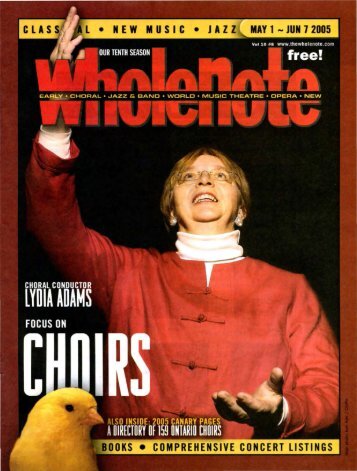

Alison Mackay and Suba Sankaran “

- Page 13 and 14: WORLD VIEWS BEST OF BOTH WORLDS Com

- Page 15 and 16: with an enigmatically dense chord o

- Page 17 and 18: orchestra has to be refined, always

- Page 19 and 20: UOFTFACLTYOFMUSIC DANIEL FOLEY Robe

- Page 21 and 22: KOERNER HALL 2019.20 Concert Season

- Page 23 and 24: Clockwise from top left: Frank Sina

- Page 25 and 26: SIM CANETTY-CLARKE WILLEKE MACHIELS

- Page 27 and 28: !! FEB 21, 8PM: The Royal Conservat

- Page 29 and 30: RUTH WALZ Peter Sellars (left) and

- Page 31 and 32: A previously unreleased conceptual

- Page 33 and 34: JESSICA GRIFFIN Ola Gjeilo relevant

- Page 35 and 36: eflecting how there is always someo

- Page 37 and 38: moment when she has to split with h

- Page 39 and 40: accommodate the trumpet mouthpiece.

- Page 41 and 42: ●●Summer@Eastman Eastman School

- Page 43 and 44: Hall, 651 Dufferin St. 437-233-MADS

- Page 45 and 46: ●●2:00: Rezonance Baroque Ensem

- Page 47 and 48: Thomson Hall, 60 Simcoe St. 416-872

- Page 49 and 50: and Gelato, 1006 Dundas St. W. 647-

- Page 51 and 52: Sankaran, choral director. George W

- Page 53 and 54: Cumberland. Chaucer’s Pub, 122 Ca

- Page 55 and 56: C. Music Theatre These music theatr

- Page 57 and 58: Russell Malone Anthony Fung George

- Page 59 and 60: Clubs & Groups ●●Feb 09 2:00: C

- Page 61 and 62: February’s Child is Beverley John

- Page 63: to name but a few (i.e. the ones I

- Page 67 and 68: having unwittingly fathered an ille

- Page 69 and 70: VOCAL Vivaldi - Musica sacra per al

- Page 71 and 72: production from Sardinia’s Teatro

- Page 73 and 74: the playing is elegant and the ense

- Page 75 and 76: composer. His career spanned almost

- Page 77 and 78: JAZZ AND IMPROVISED Taking Flight M

- Page 79 and 80: several albums which push the bound

- Page 81 and 82: Creation - such as The Nomad and Ma

- Page 83 and 84: REMEMBERING Remembering ERROL GAY F

- Page 85 and 86: TS Toronto Symphony Orchestra RACHM

- Page 87 and 88: without a net, the artist lacking a

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...