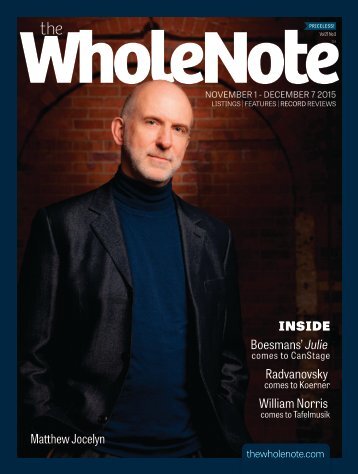

Volume 21 Issue 3 - November 2015

- Text

- November

- Toronto

- Jazz

- Arts

- Symphony

- Orchestra

- Musical

- Theatre

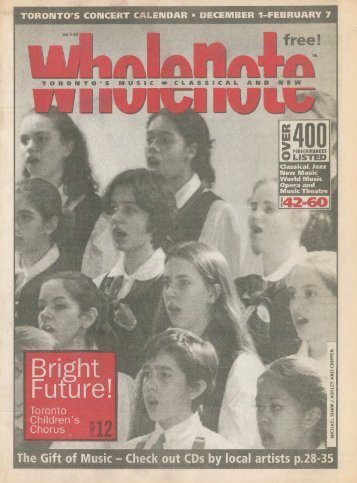

- Choir

- Performing

- Volume

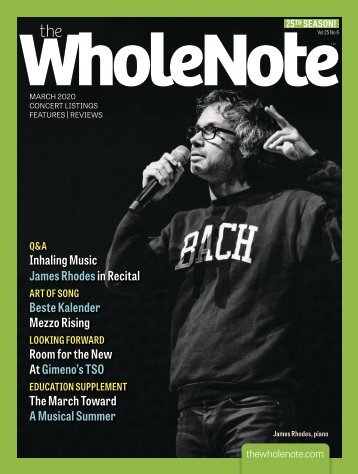

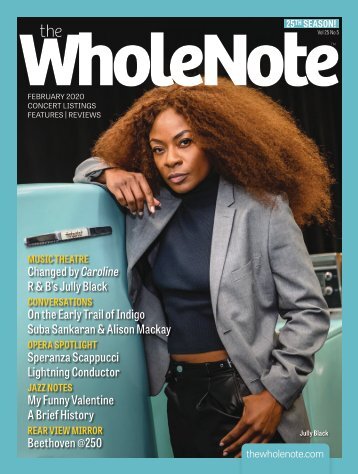

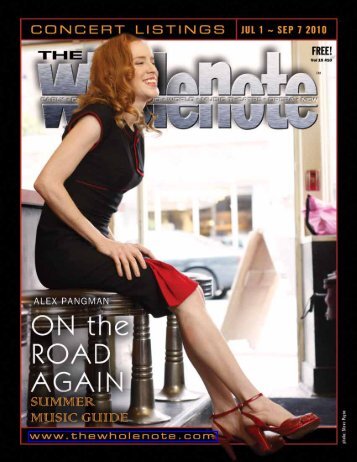

"Come" seems to be the verb that knits this month's issue together. Sondra Radvanovsky comes to Koerner, William Norris comes to Tafel as their new GM, opera comes to Canadian Stage; and (a long time coming!) Jane Bunnett's musicianship and mentorship are honoured with the Premier's award for excellence; plus David Jaeger's ongoing series on the golden years of CBC Radio Two, Andrew Timar on hybridity, a bumper crop of record reviews and much much more. Come on in!

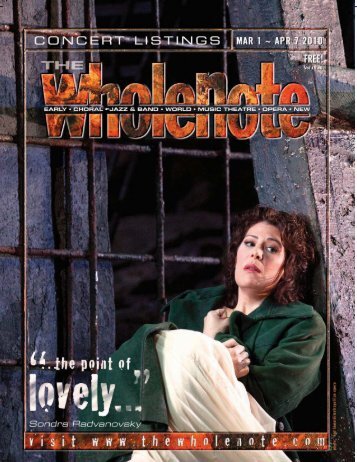

Beat by Beat | Art of

Beat by Beat | Art of Song Five Sopranos and A Mezzo HANS DE GROOT Emma Kirkby: It has sometimes seemed to me that my interest in early music began with listening to Kirkby. When I checked dates, I realized that that was not true. I bought my first early music LP (two of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, conducted by August Wenzinger) when I was a schoolboy in the early 50s, while Kirkby’s career did not begin until 1971 when she joined the Taverner Choir as a founding member. But my mistake highlights the fact that Kirkby’s singing has been central to early music performances ever since. On October 18 she and her accompanist, the fine lutenist Jacob Lindberg, gave a recital of English music ranging from William Byrd to Henry Purcell at Trinity College Chapel. Now that Kirkby is in her mid-60s the incomparable beauty of her singing is also layered with a lifetime of nuance; every presentation provides a lesson in how these songs can be delivered. In the first half of the program we heard a number of students, members of the University of Toronto’s Schola Cantorum. Until recently the University had not shown much interest in early music but this changed with the appointment of Daniel Taylor (best known as a countertenor but now also a conductor) as Early Music Area Head. Many of these performances were very fine, a tribute to the singers but also to Taylor’s leadership and to the extra coaching the singers received from Kirkby and Lindberg. Agnes Zsigovics: Kirkby studied classics at Oxford University and became a schoolteacher. At that time she would have had no notion that a professional career could be built on the singing of early music. That is no longer the case and Kirkby’s career is one reason why that change became possible. There are now many singers who specialize in Early Music and one of the finest is a Canadian soprano Agnes Zsigovics whom we shall be able to hear on November 14 with the Ottawa Bach Choir and York University Chamber Choir in a performance of Bach’s Mass in B Minor at Grace Church on-the-Hill. The other soloists are Daniel Taylor, alto, Rebecca Claborn, mezzo, Jacques- Olivier Chartier, tenor, Geoffrey Sirett, baritone, and Daniel Lichti, bass-baritone. The conductor is Lisette Canton. When I asked for an interview with Zsigovics, she accepted readily and added: “Isn’t it every soprano’s wish to talk about themselves all day long?” I decided not to take this too literally and I was right not to do so. She is not a self-absorbed diva but a down-to-earth and disciplined artist committed to her craft. As a young woman she sang in choirs at school and as a member of the Bell’Arte Singers. Her first big break came in 2005, when she sang with the Toronto International Bach Festival and was asked by the conductor, Helmut Rilling, to sing the soprano solo in Bach’s Cantata BWV106 (the Actus Tragicus). Daniel Taylor heard her and invited her to sing part of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater at a private function and to join the Theatre of Early Music. In 2007 she sang in Bach’s St. John Passion under Rilling with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. I have heard her four times in recent years: in the virtuoso soprano part of Allegri’s Miserere and as Belinda in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (both with the Theatre of Early Music), in Vivaldi’s Gloria (with Tafelmusik) and as the soprano soloist in the Grand Philharmonic Choir’s performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in Kitchener last Good Friday. She has now sung outside Ontario many times. In May she performed at the Bethlehem Bach Festival (and she will return there next May) and she took part in the reconstructed St. Mark Passion by Bach at the Festival d’Ambronay in France in September. As for the near future: in January she will be in Montreal in a program of Bach cantatas, in April she will sing Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers in Chicago with Music of the Baroque and in May she will sing Bach in Calgary. Agnes Zsigovics and Benjamin Butterfield with the Bach Choir of Bethlehem in a performance of the Bach Mass in B minor at the Bethlehem Bach Festival (2014) She will make her debut in a fully staged operatic performance when she will sing the role of Eurydice in Gluck’s Orfeo ed Eurydice in Grand River, Michigan. We can also hear her voice on several recordings, two with the Theatre of Early Music (The Voice of Bach on RCA, and The Heart’s Refuge on Analekta) and one with Les Voix Baroques and the Arion Baroque Orchestra under Alexander Weimann (Bach’s St. John Passion, on ATMA). Zsigovics is now looking at the possibility of launching her first solo recording. Simone Osborne: Like Zsigovics, Simone Osborne could be described as a lyric soprano but, unlike Zsigovics, she is primarily an opera singer. In 2008, when she was 21, she won the Metropolitan Opera National Concert Auditions. In 2012, Jeunesses Musicales Canada chose her as the first winner of the Maureen Forrester Award. She was a member of the Ensemble Studio of the Canadian Opera Company and has performed a number of roles for the COC on the main stage: Pamina in Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Oscar in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera, Gilda in Verdi’s Rigoletto, Nannetta in Verdi’s Falstaff and Lauretta in Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. She will return to the COC later this season to sing Micaela in Bizet’s Carmen. On November 12 and 14, we have a chance to hear her in concert with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Part of the TSO’s Decades Project, that concert will show the diversity of styles in works from the first decade of the 20th century. Osborne will sing three pieces: the aria Depuis le jour from Charpentier’s Louise, first performed in 1900; the Song to the Moon from Dvořák ‘s Rusalka (1901) and the soprano solo in the final movement of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony (1901). Isabel Leonard: The Women’s Musical Club of Toronto can always be relied on to provide artists and programs of interest. I, myself, am very much looking forward to the recital by the American mezzo Isabel Leonard on November 19 inWalter Hall. A few seasons ago Leonard sang with the COC in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito and she was splendid in the role of Sesto. The recital will include works by Montsalvatge, de Falla, Ives, Higdon and others. Sondra Radvanovsky: I last heard Sondra Radvanovsky in a dazzling performance as Queen Elizabeth I in Donizetti’s Roberto Devereux for the COC. On December 4 she will give a recital in Koerner Hall. The program includes the aria Sposa son disprezzata from Bajazet by Vivaldi, the Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss, the Song to the Moon from Dvořák ‘s Rusalka and songs and arias by Bellini, Barber, Giordano and Liszt. Magali Simard-Galdès: Jeunesses Musicales Canada has announced that the winner of the 2015 Maureen Forrester Prize is the soprano Magali Simard-Galdès. The prize consists of a 30-city tour in which she will perform a program of art songs including a new song cycle by Tawnie Olson, commissioned by the Canadian Art Song Project. Hans de Groot is a concertgoer and active listener, who also sings and plays the recorder. He can be contacted at artofsong@thehwolenote.com. 26 | Nov 1 - Dec 7, 2015 thewholenote.com

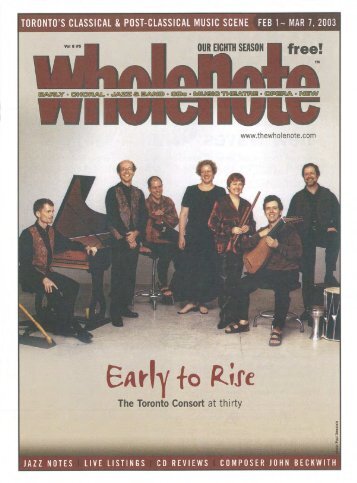

Beat by Beat | Early Music But When In Naples ... DAVID PODGORSKI There’s an anecdote from a book I read once that’s been bothering me for a while. In the memoir Kitchen Confidential, the American celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain describes the following altercation he had with one of his Italian chefs at a restaurant he owned: “Gianni had taken one look at my chef de cuisine, shaken his head and warned, ‘Watch out for dees guy. He’ll stobb you inna back,’ making a stabbing gesture as he said it. “What? What’s his problem? He’s Sicilian?’ I asked jokingly, knowing Gianni’s preference for all things Northern. ‘Worse,’ said Gianni. ‘He’s from Naples.’” Bourdain never explained what the problem with being Neapolitan was at any point in the rest of the book (maybe he never got around to asking Gianni), and frankly, I’ve never tried to ask anyone whether they were from Naples, Italy, or anywhere else. Was Bourdain’s chef a racist? Are Neapolitans intrinsically untrustworthy? And (most importantly) why would they be intrinsically untrustworthy to other Italians? Maybe the chef’s mistrust had to do with the fact that Naples had a history that pitted it against the rest of the Italian kingdoms for most of the last millennium: the Kingdom of Naples, comprising the city of Naples and roughly the southern half of the Italian boot, was ruled by the (French) King of Anjou from mid-13th to mid-14th century, the (Spanish) Aragonese from then to the early 16th century, the Spanish and Habsburg Empires for the next 200 years, and became a Napoleonic possession from then until 1815. That wasn’t a lot of time for Southern Italy to develop an independent, let alone pan-Italian identity, so maybe other Italians (or at least that particular Italian) are referencing the fact that, politically, Naples was in fact a French, Spanish, or Austrian province more than it was ever an Italian one. As a cultural centre, though, Naples in its prime was a fascinating place. Ethnically Italian with a Spanish influence, its position smack in the middle of the Meditarranean made it a natural port of call between the rest of the European continent and the Middle East. Naples is also largely responsible for giving us a major institution of both culture and of classical music – the modern conservatory. The Spanish regime in Naples was one of the first governments to found conservatories, which it did in Naples – initially church-run institutions to shelter and educate orphans, they later became the music schools we know today. In 17th-century Naples, with the new form of opera quickly becoming popular and a sudden high demand for trained singers and musicians throughout Italy, conservatories found themselves part of a feeder system for professional musicians and singers, as they were both amply funded and made music education a significant part of a child’s education. Vesuvius:This month, The Toronto Consort pays tribute to the music and culture of this Renaissance cosmopolis in their opening concert of the season, “The Soul of Naples.” The Consort will be performing this month at Jeanne Lamon Hall at Trinity-St-Paul’s Centre at 8pm on November 13 and 14. I’ve been looking forward to this concert for some time. The Consort is teaming up with the Vesuvius Ensemble, which is the only folk group I’ve ever encountered that specializes specifially in Renaissance Neapolitan folk music. The group has the good fortune to be led by a top-rate tenor, Francesco Pellegrino, who will be directing both Vesuvius and the Consort this time around. And if you’re a guitar fan, this is definitely the concert for you – this show features a menagerie of plucked-string instruments, including baroque guitar, theorbo and lute, as well as the far more obscure thewholenote.com Nov 1 - Dec 7, 2015 | 27

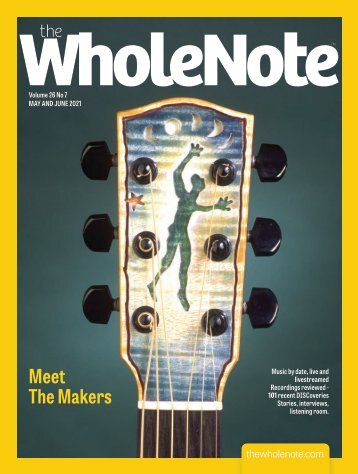

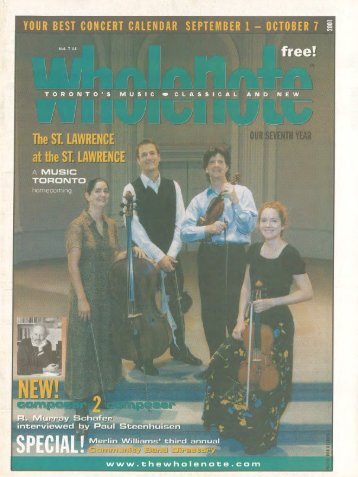

- Page 1 and 2: PRICELESS! Vol 21 No 3 NOVEMBER 1 -

- Page 3: Toronto’s Hallelujah Event! MESSI

- Page 6 and 7: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Neighbo

- Page 8 and 9: CONVERSATIONS AT THE WHOLENOTE Sond

- Page 10 and 11: “Yes there will,” she says. “

- Page 12 and 13: The idea was to appeal to new audie

- Page 14 and 15: ISABELLE FRANÇAIX Beat by Beat | O

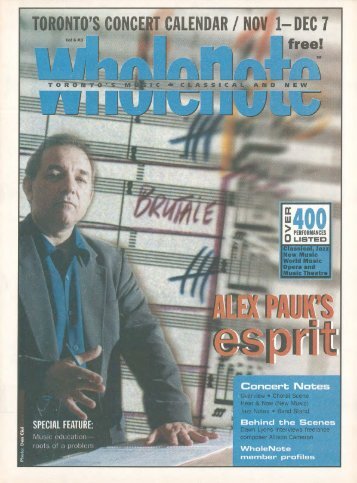

- Page 16 and 17: CBC Radio Two: The Golden Years Ale

- Page 18 and 19: naturalism aesthetic that sought to

- Page 20 and 21: • THE 7 TH ANNUAL CITY • CAROL

- Page 22 and 23: Beat by Beat | Bandstand Pun Times

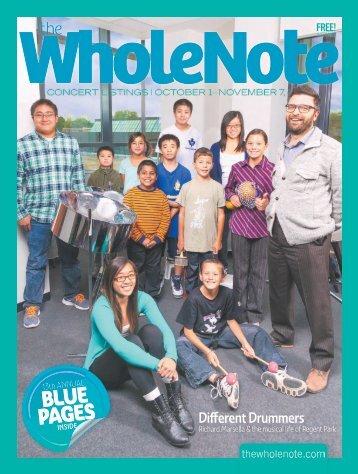

- Page 24 and 25: Oakville Children's Choir at the Wo

- Page 28 and 29: Musicians in Ordinary Beat by Beat

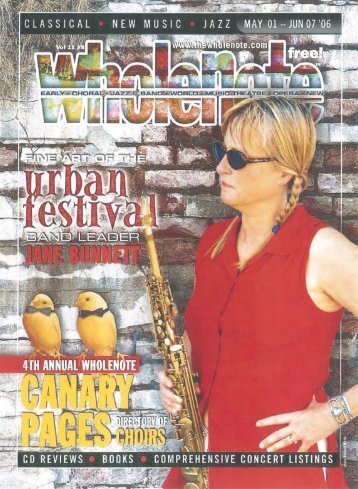

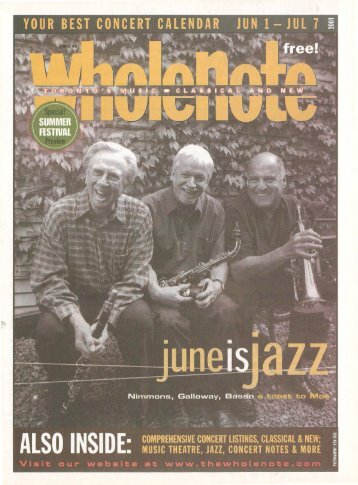

- Page 30 and 31: Beat by Beat | Jazz Stories Jane’

- Page 32 and 33: BLUE PAGES 2015/16 16th ANNUAL DIRE

- Page 34 and 35: The WholeNote listings are arranged

- Page 36 and 37: Nematallah, violin; Caitlin Boyle,

- Page 38 and 39: Toi. Door prizes and refreshments.

- Page 40 and 41: Sara Tavares & Caminho. Koerner Hal

- Page 42 and 43: & Lynn Ahrens. Fairview Library The

- Page 44 and 45: 2015 / 2016 Presents Sunday, Novemb

- Page 46 and 47: Music Series: Songs of Solomon. Ros

- Page 48 and 49: ●●6:00: Ross Petty Productions.

- Page 50 and 51: (Oakville), 262 Randall St., Oakvil

- Page 52 and 53: Wednesday November 4 ●●12:00 no

- Page 54 and 55: Wednesday December 2 ●●6:00: Do

- Page 56 and 57: Beat by Beat | Mainly Clubs, Mostly

- Page 58 and 59: Nice Bistro, The 117 Brock St. N.,

- Page 60 and 61: AUDITIONS & OPPORTUNITIES AUDITION

- Page 62 and 63: DISCOVERIES | RECORDINGS REVIEWED D

- Page 64 and 65: ultimately eliminating materials fr

- Page 66 and 67: TERRY ROBBINS Our own James Ehnes i

- Page 68 and 69: VOCAL Rimsky-Korsakov - The Tsar’

- Page 70 and 71: Melnikov’s pianoforte is again th

- Page 72 and 73: ecordings made by Childs’ quartet

- Page 74 and 75: Subcontinental Drift and the more f

- Page 76 and 77:

Old Wine, New Bottles | Fine Old Re

- Page 78 and 79:

STUART BROOMER Drummer/composer Har

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...