Volume 22 Issue 7 - April 2017

- Text

- April

- Toronto

- Jazz

- Symphony

- Arts

- Theatre

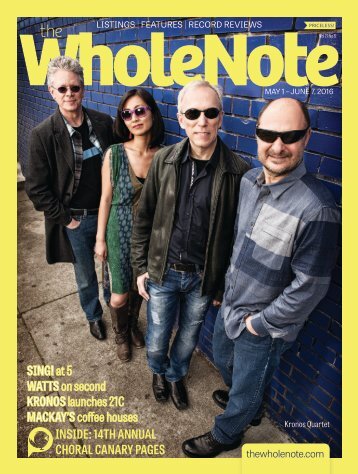

- Quartet

- Orchestra

- Choir

- Musical

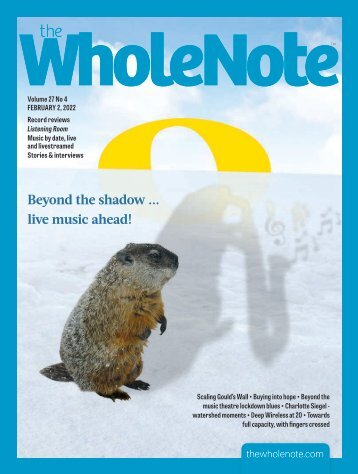

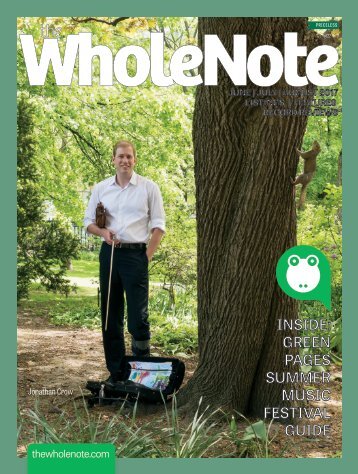

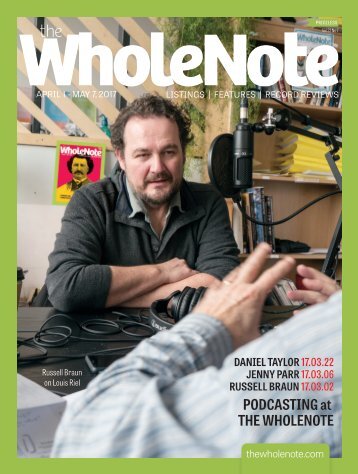

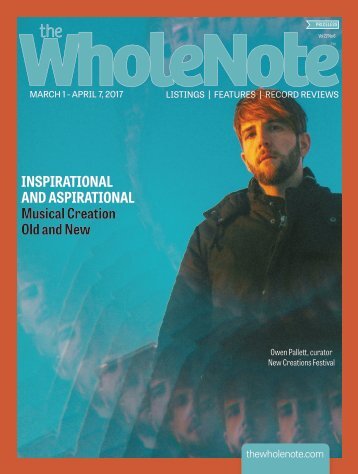

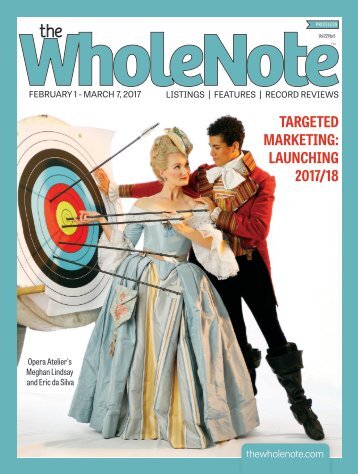

In this issue: Our podcast ramps up with interviews in March with fight director Jenny Parr, countertenor Daniel Taylor, and baritone Russell Braun; two views of composer John Beckwith at 90; how music’s connection to memory can assist with the care of patients with Alzheimer’s; musical celebrations in film and jazz, at National Canadian Film Day and Jazz Day; and a preview of Louis Riel, which opens this month at the COC. These and other stories, in our April 2017 issue of the magazine!

Beat by Beat | On Opera

Beat by Beat | On Opera Rising to the Challenge of Riel Greg Funfgeld and Dashon Burton that is only possible when it is as current as it is timeless. Jerusalem Opera Festival: Last summer’s trip to the Jerusalem Opera Festival had several memorable moments. One was sitting, late at night, on the rooftop licenced patio of the Mamilla Hotel in downtown Jerusalem, after returning from the evening’s main event, a thoroughly enjoyable outdoor performance of Rigoletto at the 6000- seat Sultan’s Pool amphitheatre, a few hundred feet down the hill. There’s something infinitely less annoying about amplification and outdoor acoustics when the surroundings are as genuinely imposing. (Although I do remember thinking, as an ambulance barrelled down the hill, klaxon blaring, alongside the amphitheatre, right on cue, that maybe this time Gilda would be saved! The second night’s performance, at the Sultan’s Pool again, titled “Opera Paradiso,” was, to my taste less successful, featuring a range of operatic moments from film, sung and performed live by singers and orchestra while the related movie excerpts flickered silently onscreen. I found myself wondering if there was perhaps a trap for the festival in trying to attract the same 6000 people two days in a row to the one venue, rather than setting the goal of doing the same show twice in a row to grow the audience, and to lay on other things, large and small, for each audience on their “other” night. A better way to build partnerships in the community, said my small-town brain. As it happens, this year’s Jerusalem Festival has just been announced, and someone else must have been thinking along the same lines I was. There will be two performances of Nabucco, June 21 and 22 at Sultan’s Pool. It will be very interesting to see what else, if anything, operatic or not, gets programmed head to head with those two performances. My favourite story from the whole visit indicates the size of the challenge ahead. We were in Tel Aviv, home base of the Israeli Opera, at the end of the visit, being shown around the props and costumes room, backstage. Our guide, an opera staff member, was talking frankly about how the two cities were completely different worlds. (“It’s an hour’s drive at a speed of 30 centuries an hour,” someone said.) The NIOC staffer described how her own children, growing up backstage among the props and costumes, had never even been to Jerusalem until they were five or six years old. Holding tight to her hand as they walked through the souks with their dizzying variety of cultural and religious garb, one of the children turned to her, pointing at someone walking by in unfamiliar attire. “Mommy, what costume is that?” the child asked. The greatest challenge for this particular festival, it seems to me, is that Jerusalem as a city is itself a living opera, on a grander, more viscerally demanding scale than anything the arts can hope to muster. It will be interesting to see how much attention this particular festival can hope to grab moving forward. David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com. CHRISTOPHER HOILE While there are several noteworthy operas on offer in April, one looms over them all. This is the COC’s first new production of Harry Somers’ Louis Riel since it premiered in 1967. Co-produced by the Canadian Opera Company and the National Arts Centre, the new production will give Canadians the rare opportunity to see what has often been called the greatest Canadian opera ever written. Written and performed for Canada’s centennial in 1967, Louis Riel is being revived for the sesquicentennial this year. Reasons for the scarcity of productions of it are not hard to see. The opera is in three acts and 17 scenes, requires a chorus, a 67-member orchestra and has 39 named roles. Composer Harry Somers and librettist Mavor Moore wanted to create an epic opera on the model of French grand opera and one could say they succeeded only too well. In an interview in March, director Peter Hinton threw light on how he plans to meet the many challenges that the opera poses. Speaking of his concept for the production, Hinton explained, “What we’ve tried to do is create a setting that can serve each of the locations of the opera but also create a sort of container of imagery that in some ways sets the entire opera at the trial of Louis Riel. So on the one hand the set resembles Fort Garry, an enclosure, the contrast of a colonized building against an incredible landscape of the land, and also a courtroom where the events of history are put on trial and we’re examining the motivations and intentions behind enormous ideas like governments, justice, confederation. So it was very challenging but very exciting because the ideas of the opera are really big, the history is very big, and not surprisingly it’s very contemporary. Yes, it’s a historical story, but it’s one that continues to speak to us today.” Hinton said that Somers and Moore made an intriguing choice of subject for an opera meant to celebrate Canada’s centennial: “I thought it was very interesting that they chose the history of Louis Riel. And I think that’s a very key kind of distinction because when I first sat down to listen to it I suspected it might be a very pro-Canada, ‘we are one nation,’ idealized kind of history telling. But I was really taken with how critical it is, how it brought forward the problems of Confederation, that it exposed Sir John A. Macdonald and his political motivations for Confederation in a very critical way. And so it poses very contemporary questions about what are we commemorating, what are we celebrating, what, in addition to our history of achievement, [are] our losses, our injustices, what continues to be needed to be worked out and expressed and understood today.” Thus, Hinton’s concept for the opera as a trial means more than Riel’s trial. Canada and how it was founded are also on trial. In addition, Hinton points out, he is re-examining the opera itself: “In another way we’re sort of putting the opera on trial. Clearly, if the COC were to take on creating a new opera today about Louis Riel, it would have more indigenous and Métis involvement in the creation of it. So even more than the challenges of staging the narrative of Louis Riel, the politics of it have been much more challenging and very, very difficult to reconcile oneself with because opera itself might be characterized as one of the most colonial art forms because its roots are so Eurocentric.” The solution, as he explains it, was to treat Harry Somers’ and Mavor Moore’s opera as an artifact of its time. “It reflects very much the aesthetic sensibilities of contemporary music of the 1960s and it has great dramatic strength and power and beauty. It also has many colonial biases. So part of the job here is to do the opera and let its beauty be heard and soar and not be afraid to cast light on its biases; not to pretend the opera is an Indigenous creation 12 | April 1, 2017 - May 7, 2017 thewholenote.com

DAVID COOPER – it is definitely created by two white settler guys – but to try to open up a more inclusive representation in the show. “And I have to say honestly that [COC General Director] Alexander Neef knew exactly what I was talking about…it took me a long time to make a commitment to be involved because of issues about inclusion and appropriation especially in light of Truth and Reconciliation. I’m very aware of my privilege and my own cultural heritage as a director for the piece. So I really had to think a way through that I could contribute without continuing a legacy of misrepresentation.” To achieve this, Hinton has re-envisioned the opera’s chorus: “In the original production there was one very large opera chorus who played a variety of roles from members of the Métis Assembly to demonstrators at an Orangemen’s protest in Toronto. And I decided to split up the chorus and identify them culturally. So we in fact have two choruses in this production – one which we are calling the Parliamentary Chorus. This chorus is in modern dress and sing the allocated choral parts in the score but they are removed from the action. They sit above in a gallery not Peter Hinton unlike visitors to a house of parliament and comment on the opera, debate the opera, encourage characters within the narrative to act or not. But they do nothing. They have no physical impact on the story or its outcome. They comment. “In contrast and in equal representation in the show is a 35-member Indigenous chorus who are a physical chorus and we’re calling them the Land Assembly. They physically embody the world in which the narrative Riel is enacted and are directly involved in all of the action but are not given a voice. So in many respects the opera is one about silence, about who speaks on behalf of whom, and who gets a voice and who doesn’t. And so what I’m very hopeful about is that our Land Assembly brings a very strong Indigenous representation of bodies on stage and has an impact of reminding the audience as they see this story enacted that land is also about people. And the opera is also very much people and groups and where does someone stand as an individual, what do they represent. That’s one aspect of the show that will be very different from the way it was done 50 years ago.” The COC has cast Indigenous men 2 0 1 6 / 1 7 PART OF THE D A N C E C O L L E C T I O N EIFMAN BALLET ST. PETERSBURG RED GISELLE “Boldly expressive and extraordinary. ” – Vogue 40 TH ANNIVERSARY TOUR May 11 – 13 “ A masterwork of electrifying performances.” – San Francisco Chronicle Red Giselle © Eifman Ballet St. Petersburg PRESENTING PARTNER CO-PRESENTED WITH MEDIA PARTNERS: sonycentre.ca 1.855.872.SONY (7669) thewholenote.com April 1, 2017 - May 7, 2017 | 13

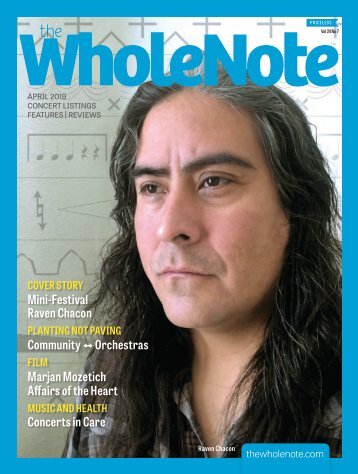

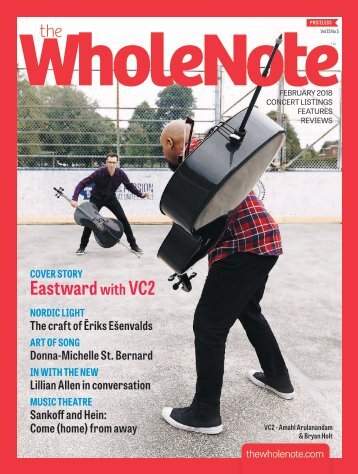

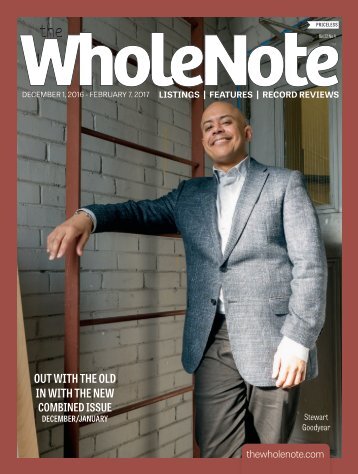

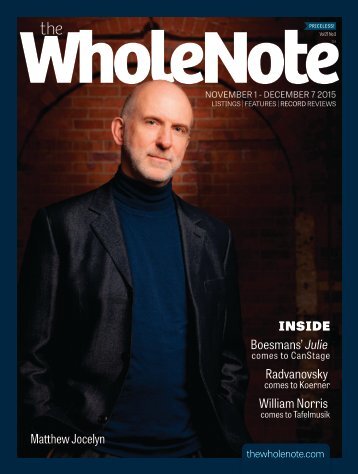

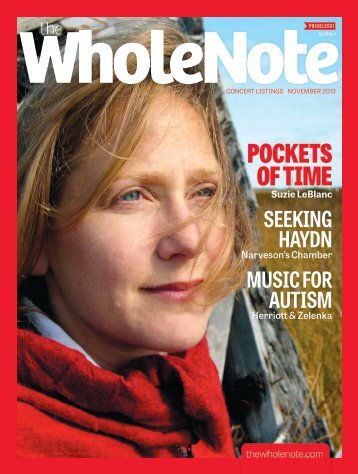

- Page 1 and 2: PRICELESS Vol 22 No 7 APRIL 1 - MAY

- Page 3 and 4: 2017. 2018 @ AWE INSPIRING. CREATIV

- Page 5 and 6: Volume 22 No 7 | April 2017 FEATURE

- Page 7 and 8: INDEX OF ADVERTISERS Adam Sherkin..

- Page 9 and 10: thewholenote.com April 1, 2017 - M

- Page 11: Bach in Bethlehem, Verdi in Jerusal

- Page 15 and 16: KOERNER HALL IS: “ A beautiful sp

- Page 17 and 18: Beat by Beat | Early Music No Silve

- Page 19 and 20: Beat by Beat | Classical & Beyond S

- Page 21 and 22: Dvořák’s charming “Dumky” T

- Page 23 and 24: Beat by Beat | In with the New Sing

- Page 25 and 26: Beat by Beat | Art of Song Pop Goes

- Page 27 and 28: introduction to the form. You will

- Page 29 and 30: KIM VANDERDOOY around Easter and ma

- Page 31 and 32: WILLIAM P. GOTTLIEB - THIS IMAGE IS

- Page 33 and 34: KAREN E. REEVES present “Tabla an

- Page 35 and 36: performed a few times in recent yea

- Page 37 and 38: Brahms, Daley, Enns, Fauré, Rudoi

- Page 39 and 40: Reflections. Songs of hope and peac

- Page 41 and 42: Royal Conservatory, 273 Bloor St. W

- Page 43 and 44: ●●7:00: Lorne Park Baptist Chur

- Page 45 and 46: Hall, Edward Johnson Building, Univ

- Page 47 and 48: ●●8:00: Royal Conservatory of M

- Page 49 and 50: O Canada! 150th Celebration! With E

- Page 51 and 52: ●●3:00: Les Amis. In Concert. W

- Page 53 and 54: Presented by: based on the books an

- Page 55 and 56: 5pm Grateful Sunday; 9pm Evan Desau

- Page 57 and 58: Lectures, Salons, Symposia ●●Ap

- Page 59 and 60: MUSIC AND HEALTH How Music Matters

- Page 61 and 62: to study with Alberto Guerrero. An

- Page 63 and 64:

L/R All this is by way of a long-wi

- Page 65 and 66:

Given his wonderful playing on the

- Page 67 and 68:

flues. It’s built and voiced to p

- Page 69 and 70:

who, in 1900, became a student of A

- Page 71 and 72:

will after listening to this rock-b

- Page 73 and 74:

Common Ground KMJO (Kirk MacDonald

- Page 75 and 76:

y air/wind movement, and Bach’s s

- Page 77 and 78:

Azrieli Music Prizes Recognizing ex

- Page 79 and 80:

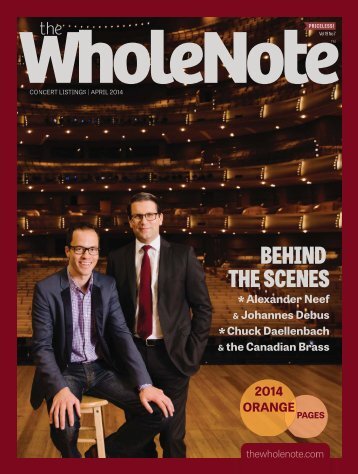

Johannes Debus Bang on a Can All-St

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...