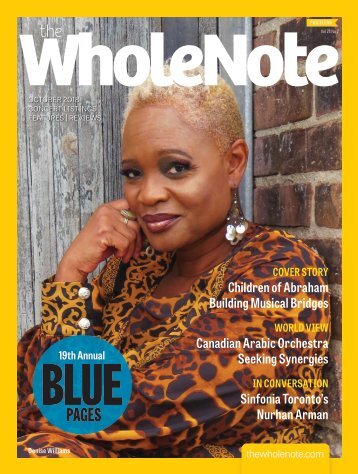

Volume 23 Issue 8 - May 2018

- Text

- Choir

- Toronto

- Musical

- Choral

- Singers

- Arts

- Theatre

- Concerts

- Jazz

- Festival

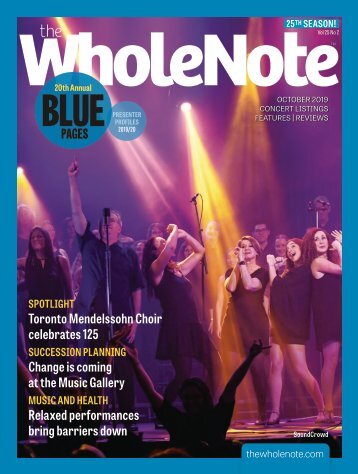

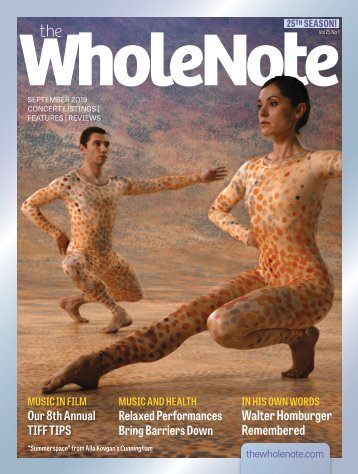

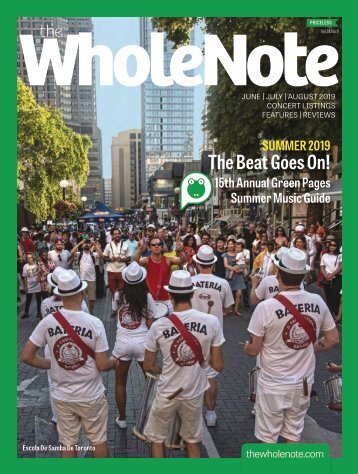

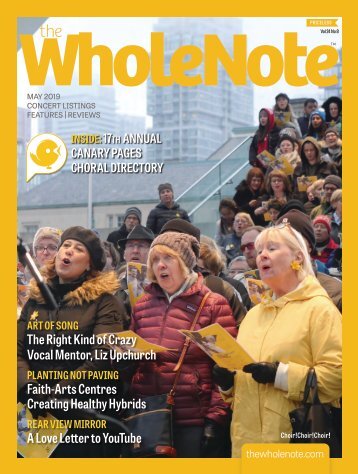

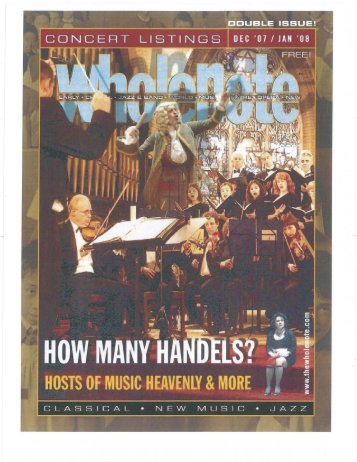

In this issue: our sixteenth annual Choral Canary Pages; coverage of 21C, Estonian Music Week and the 3rd Toronto Bach Festival (three festivals that aren’t waiting for summer!); and features galore: “Final Finales” for Larry Beckwith’s Toronto Masque Theatre and for David Fallis as artistic director of Toronto Consort; four conductors on the challenges of choral conducting; operatic Hockey Noir; violinist Stephen Sitarski’s perspective on addressing depression; remembering bandleader, composer and saxophonist Paul Cram. These and other stories, in our May 2018 edition of the magazine.

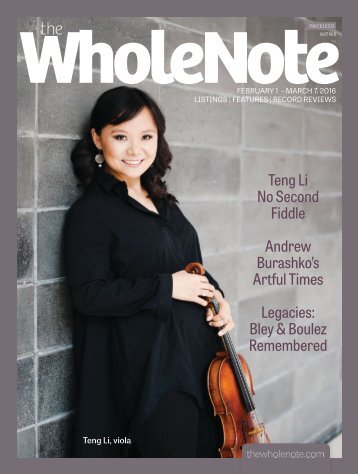

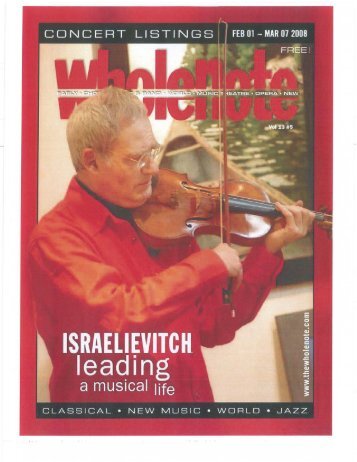

MUSIC AND HEALTH

MUSIC AND HEALTH ADDRESSING DEPRESSION: Stephen Sitarski, violin VIVIEN FELLEGI BO HUANG It was the first time that Dvořák’s joyous Symphony No.8 had failed to move Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony’s concertmaster Stephen Sitarski. He knew each note by heart, and he usually looked forward to its most exhilarating passages. But on that matinee performance at the packed Guelph River Run Centre over a decade ago, something was very wrong. Though his body churned out the melody by rote, he felt like a robot. “I was disconnected completely from the music – I felt empty and soulless,” he says. For a moment he considered getting up, apologizing to the conductor and walking offstage. But years of discipline kicked in and he finished the piece. “I’m someone who doesn’t give up, who sacrifices to the end to get the job done.” Shortly after that incident Sitarski was diagnosed with severe depression. Sitarski is not alone. The rate of depression is higher amongst musicians than in the general population, says Dianna Kenny, professor of psychology and music at Australia’s University of Sydney. In one study, 32 percent of one orchestra’s players ticked off symptoms of depression in a questionnaire. The artistic temperament puts many musicians at risk for depression, says Susan Raeburn, clinical psychologist in Oakland, California. The same sensitivity that drives them to self-expression makes them vulnerable to emotional pain. Children’s musical education may ramp up their sensitivity to stress, says physician Dr. John Chong, director of the Musicians’ Clinics of Canada. Traditional teachers hold students to exacting standards, ripping them apart when they fall short. Auditions and competitions add to the relentless judgment. Some young musicians internalize these critical voices, becoming perfectionists who are never satisfied with themselves, says Raeburn. They are especially vulnerable to developing severe, suicidal depression, she says. Some of these prodigies resent the loss of their childhood, says Kenny. “Instead of exploring the world, they’re locked away in their music room practising.” Life doesn’t get any easier for adult artists. Orchestral musicians face relentless competition for few spots, financial insecurity, long hours, inadequate rehearsals, and exhausting tours which take them away from loved ones, says Chong. But the psychological pressures are the toughest. While young musicians are encouraged to find their own voice, recording companies, agents and conductors stifle their creativity, says Chong. Conflict within the orchestra can also diminish workplace satisfaction, says Kenny. “An orchestra is a very closed universe – when you see people day in and day out, then travel together in close quarters when on tour…certain animosities will develop,” she says. Public humiliations by abusive conductors can add to the strife, says Chong. Sitarski suffered many of these pressures over his career. He has always been emotional, turning to music to express his feelings. “I am compelled to play – if I don’t perform I feel emptiness.” But some of his teachers sabotaged his enjoyment, comparing him unfavorably to other students and belittling him when he lost a competition. Sitarski soon adopted their impossibly high expectations. “If we don’t shoot for perfection, we don’t improve, but we beat ourselves up when we don’t reach it,” he says. Sitarski encountered a whole new set of stressors after graduation. He endured anxiety-provoking auditions, hidden behind a screen, knowing that his future depended on only ten minutes of playing. After winning one of a few coveted spots in the Winnipeg Symphony, he had little bargaining power to challenge the exhausting workload, insufficient preparation and arduous tours. Losing his artistic integrity was even worse. One conductor at the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony was especially authoritarian. “He would often choose interpretive styles and tempi that were extremely uncomfortable, but when someone would express that he would dismiss them outright,” says Sitarski. Ironically, it was the firing of this particular conductor that pushed Sitarski over the edge. Some of those who opposed the dismissal blamed Sitarski, the concertmaster, giving him the cold shoulder. But the show had to go on. “The repression was huge – we had to sit with a smile pasted on our faces for the sake of the audience,” he says. The body keeps score of these kinds of cumulative mental injuries, says Chong. Each time we’re stressed, we activate the fight or flight system which helps us cope with a threat. The hormone cortisol is a weapon in this arsenal, releasing proteins called cytokines which generate inflammation. With repeated crises, these chemicals accumulate in the muscles, causing soreness, and attack brain cells, precipitating depression. The illness dulls thinking, flattens emotions and sucks the joy out of life. “You’re like a zombie,” says Chong. Some musicians funnel their emotional suffering into physical agony, developing aches in their joints and muscles, says Kenny. Chronic stress can also spark stage fright in musicians with reactive nervous systems or difficult childhoods, says Kenny. Depression can follow. “Musicians know they’re going to get terrible anxiety every time they get onstage, and this wears them out,” she says. 20 | May 2018 thewholenote.com

As the psychological insults piled up like toxins in his system, Sitarski’s body succumbed to illness. First he grappled with overwhelming performance anxiety, triggering a racing heart, clammy hands, and sheer terror before a show. While the problem wasn’t new, it increased after the rift. “I worried when I went onstage that I’d screw up and the ‘other side’ would feel vindicated.” Then Sitarski got sicker. He was always exhausted, and his normally efficient reflexes slowed down. “I would be practising something and it just wouldn’t stick – I’d stumble all over and make mistakes.” Worse was the nihilism, the certainty that nothing mattered. And though he didn’t feel tempted to harm himself, he recalls one sobering night when he understood the rationale for suicide. “It’s this very cold, logical decision made by someone who has lost his ability to feel any kind of joy.” But Sitarski kept soldiering on until one day he woke up with a kink in his neck. “It was my body’s signal telling me that I couldn’t keep doing what I was doing.” He tried massage, acupuncture and physiotherapy. Nothing worked. Finally his family doctor referred him to the Musicians Clinics of Canada, where, Sitarski says, Chong took one glance and diagnosed him with depression. Awareness of a condition can lead to effective ways of addressing it. Antidepressants can address the biochemical imbalances, says Chong. Dialectical behaviour therapy teaches self-soothing techniques such as mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises and physical exertion which can calm the nervous system and keep emotions in check, says Raeburn. Therapy can be another important ingredient in healing. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) focuses attention on the rigid and self-critical thinking of depressed clients, substituting extreme statements like “Either I’m perfect or I’m total crap,” with more balanced assessments, like “No one’s perfect,” says Raeburn. Newer versions of CBT can help some patients defuse disturbing thoughts and feelings by stepping back and observing them non-judgmentally. Psychodynamic therapy likewise enables some depressed musicians to dig deeper into the root causes of their ailment, mining the layers of trauma and uncovering the buried emotions which combusted into illness. These could include a teacher’s insistence on winning, a conductor’s humiliation, or a fraught domestic situation – anything that causes uncontrolled anger to ignite the nervous system’s stress response. Once these factors come to light, some musicians can make healthier choices in their lifestyles. Finally, interpersonal neurobiology can work to redress dysfunctional relationships. Children whose parents were not attuned to their needs have difficulty trusting people and are vulnerable to anxiety and depression, says Chong. For instance, the prodigy whose stage parents value only his genius, will “freak out” if he doesn’t triumph in the Chopin contest. A therapist can guide insights into these unhealthy patterns and model secure and healthy attachments, says Raeburn. Sitarski’s first visit with Dr. Chong was pivotal. An antidepressant recharged his energy and meditation helped him to relax. A counsellor reconnected Sitarski with his numbed-out feelings. “I’m much better now at recognizing when some button is pushed.” He began to realize that just going to work every day was jarring. “I couldn’t see that group of people without bringing back all these unbelievably intense negative emotions,” he says. Awareness led Sitarski to reboot his life. “I renewed my outlook and my career, and began enjoying things again.” Sitarski left the Kitchener-Waterloo orchestra, becoming concertmaster of the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra a year later. He recharged his ambition with new opportunities, freelancing for the National Ballet, the Canadian Opera Company and the Toronto Symphony. Sitarski has also become a mental health advocate. He began instructing Performance Awareness at The Royal Conservatory’s Glenn Gould School, a course which points out the challenges unique to “I would be practising something and it just wouldn’t stick – I’d stumble all over and make mistakes.” Worse was the nihilism, the certainty that nothing mattered. musicians, and showcases resources such as yoga to tackle the potential pitfalls. Because he’s gone public with his struggles, the young musicians sometimes approach him for advice on their own problems. “Sharing my experience so someone maybe doesn’t have to go through it makes me feel better,” he says. Sitarski’s journey through depression has helped him crystallize his identity. “I know who I am and I’m comfortable in my skin,” he says. And though he still relies on medication to keep the demons at bay, he’s grateful for his health and hopeful about the future. Best of all, he has reconnected with the magic of music. On this particular night the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra is performing Dvořák’s New World Symphony at the FirstOntario Concert Hall. Sitarski feels every note beating in his blood and his colleagues mirror his motions to stay in synchrony. His bow resurrects the composer’s long-ago lament, conjuring from the faded score a pulsing pathos. The audience absorbs the players’ energy and refuels them with its own electricity. Sitarski revels in the intimacy of this interplay. “I’ve become a human being again,” he says. Vivien Fellegi is a former family physician now working as a freelance medical journalist. Celebrating 200 years 1818-2018 MetUnited Music MetUnitedMusic SATURDAY, MAY 26 • 7:30PM Show Tunes for 200 A multimedia journey through music for the theatre from 1818 to today. From Rossini, Puccini and Lehar, to Gershwin, Sondheim and more! FEATURING: Annie Ramos, soprano; Julia Barber, mezzo; Charles Davidson, tenor with chorus, band and special guests Admission /10 ages 18 and under. SUNDAY, MAY 27 • 1:30PM Metropolitan Silver Band Anniversary Concert Donations accepted For more information, contact Dr. Patricia Wright at patriciaw@metunited.org or 416-363-0331 ext. 26. 56 Queen Street East, Toronto • www.metunited.org thewholenote.com May 2018 | 21

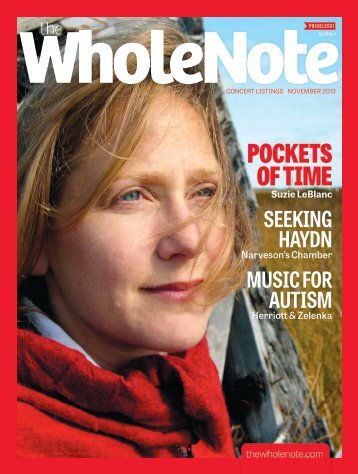

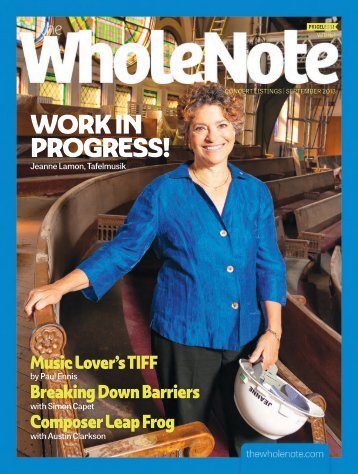

- Page 1 and 2: PRICELESS Vol 23 No 8 MAY 2018 CONC

- Page 3 and 4: 2017/18 SEASON OVER 90% SOLD! BEETH

- Page 5 and 6: 2308_MayCover.indd 2 PRICELESS Vol

- Page 7 and 8: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN And the

- Page 9 and 10: FEATURE BACH HOMECOMING: Organist R

- Page 11 and 12: FEATURE THE ICING ON THE CHORAL CON

- Page 13 and 14: live.” I appreciate his candour,

- Page 15 and 16: BO HUANG Xin Wang violinist Laura D

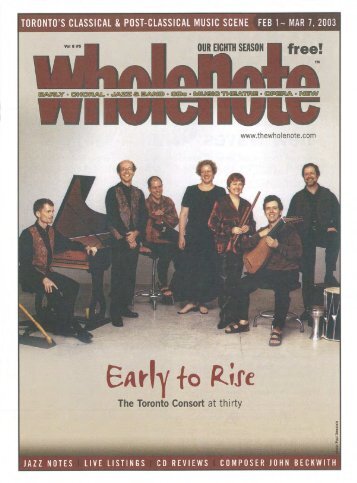

- Page 17 and 18: Once the decision was made, last su

- Page 19: Glionna Mansell Presents A Music Se

- Page 23 and 24: music. Minimalism is the one common

- Page 25 and 26: Sondheim and his work, in addition

- Page 27 and 28: Beat by Beat | On Opera Hockey Noir

- Page 29 and 30: Beat by Beat | Art of Song Where Ha

- Page 31 and 32: whose “text conjures up so many v

- Page 33 and 34: same name that starred Gene Kelly a

- Page 35 and 36: Toronto Bach Festival The month of

- Page 37 and 38: practice, instrumentation and music

- Page 39 and 40: impressed by the authority of her p

- Page 41 and 42: 16th Annual Directory of Choirs

- Page 43 and 44: CONDUCTOR & ACCOMPANIST JOAN ANDREW

- Page 45 and 46: We rehearse from September to June

- Page 47 and 48: and continues its tradition of pres

- Page 49 and 50: matthew.otto@gmail.com www.incontra

- Page 51 and 52: 416-924-6211 x0 music@mnjcc.org www

- Page 53 and 54: ●●Schola Magdalena Schola Magda

- Page 55 and 56: (JK and up) from all over Scarborou

- Page 57 and 58: vocal soloists and arts organizatio

- Page 59 and 60: GREEN PAGES EARLY- BIRD SUMMER MUSI

- Page 61 and 62: Tuesday May 1 ●●12:00 noon: Can

- Page 63 and 64: on-the-Hill, 300 Lonsdale Rd. 416-9

- Page 65 and 66: Nightingale and Other Short Fables.

- Page 67 and 68: folk electronica and a new ambient,

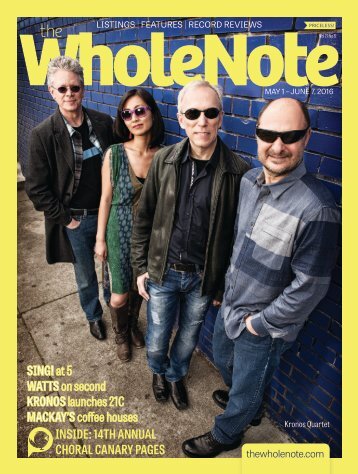

- Page 69 and 70: 21C MusiC Festival KRONOs QuaRtet W

- Page 71 and 72:

416-879-5566. and up; (sr/st

- Page 73 and 74:

Also May 30(mat & eve), 31(eve). We

- Page 75 and 76:

anniversary of the Coronation. Doug

- Page 77 and 78:

St., Kitchener. info@openears.ca. $

- Page 79 and 80:

Release Party w/ Most People. May 5

- Page 81 and 82:

●●May 30 10:00am: Jewish Music

- Page 83 and 84:

May’s Child Andrea Ludwig MJ BUEL

- Page 85 and 86:

composer who has established himsel

- Page 87 and 88:

These are fine performances of real

- Page 89 and 90:

volume is astonishing. This recordi

- Page 91 and 92:

Quixotte. Telemann composes a day o

- Page 93 and 94:

and popular music streams, a compos

- Page 95 and 96:

Seaway. With song titles such as Di

- Page 97 and 98:

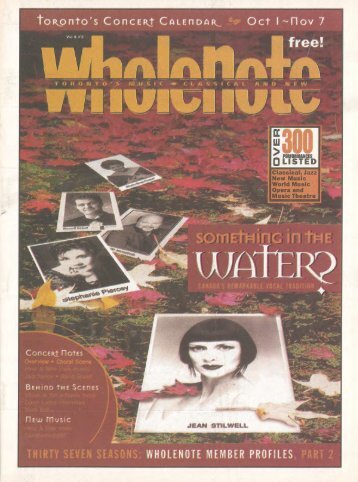

Something in the Air Rethinking the

- Page 99 and 100:

at his home in Westport CT. As 2018

- Page 101 and 102:

LOOKING BACK Risk and Promise: Paul

- Page 103 and 104:

Anthony de Mare Maarja Nuut & HH Kr

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...