Volume 24 Issue 6 - March 2019

- Text

- Composer

- Song

- Reviews

- Piano

- Performance

- News

- Events

- Listings

- Live

- World

- Choral

- Education

- Summer

- Arts

- Theatre

- Jazz

- Classical

- March

- Music

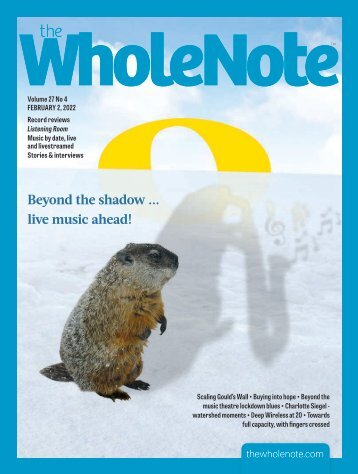

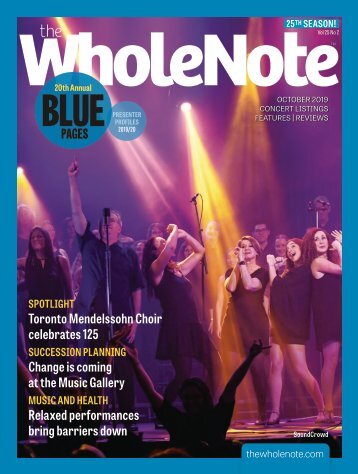

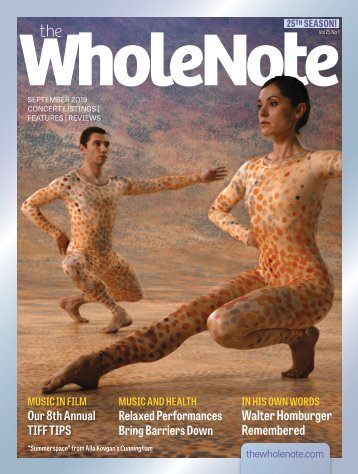

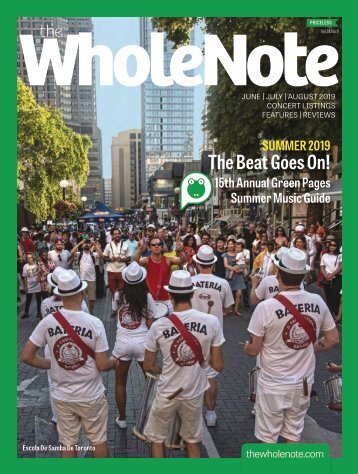

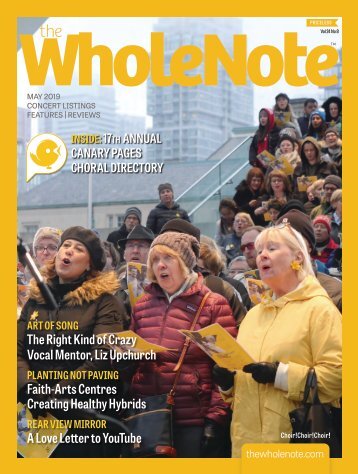

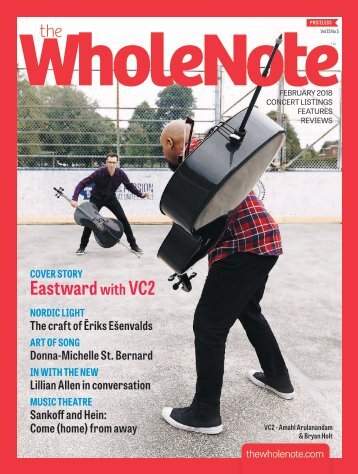

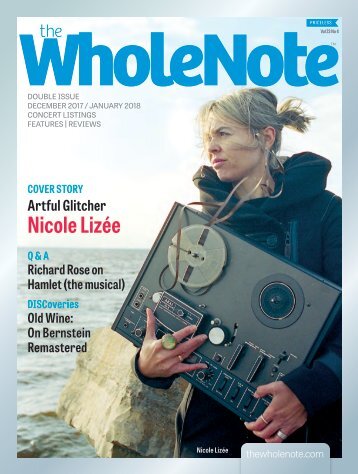

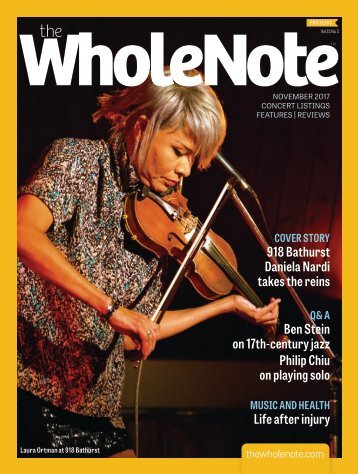

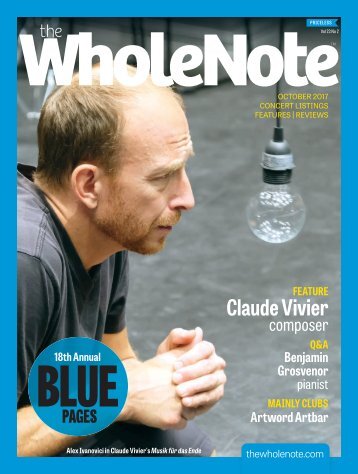

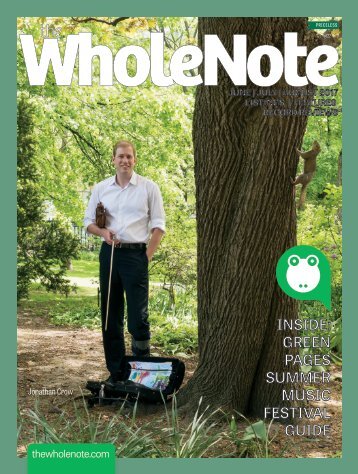

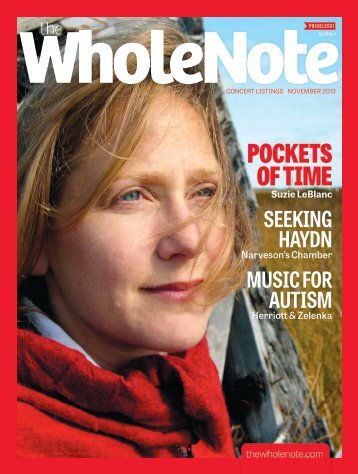

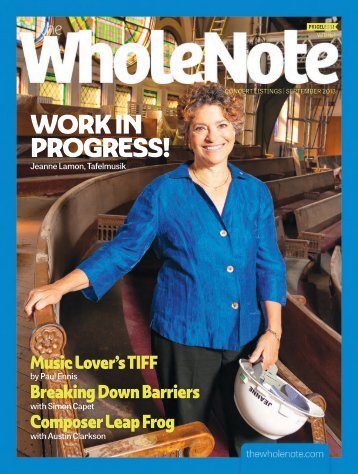

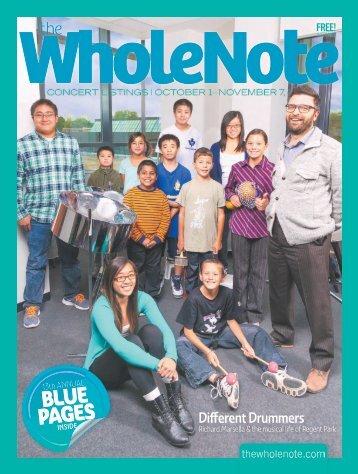

Something Old, Something New! The Ide(a)s of March are Upon Us! Rob Harris's Rear View Mirror looks forward to a tonal revival; Tafelmusik expands their chronological envelope in two directions, Esprit makes wave after wave; Pax Christi's new oratorio by Barbara Croall catches the attention of our choral and new music columnists; and summer music education is our special focus, right when warm days are once again possible to imagine. All this and more in our March 2019 edition, available in flipthrough here, and on the stands starting Thursday Feb 28.

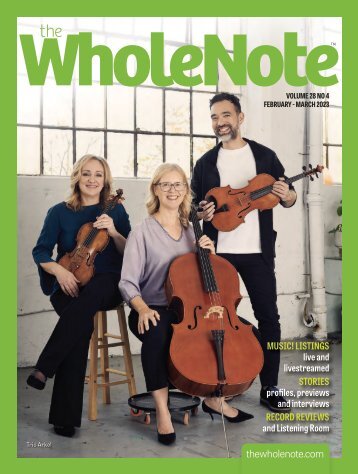

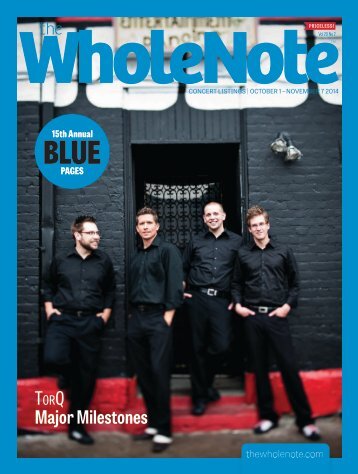

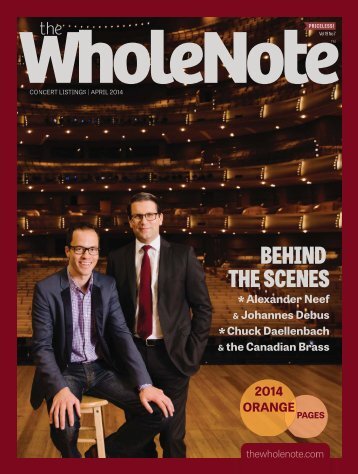

FEATURE From left to

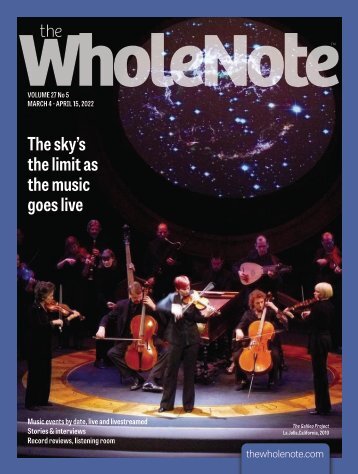

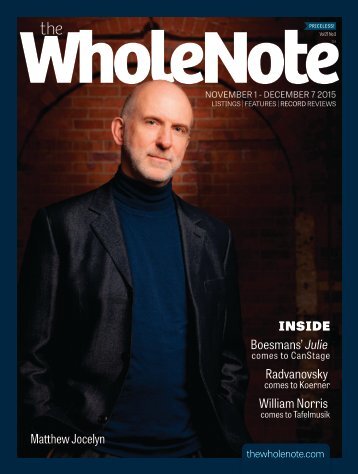

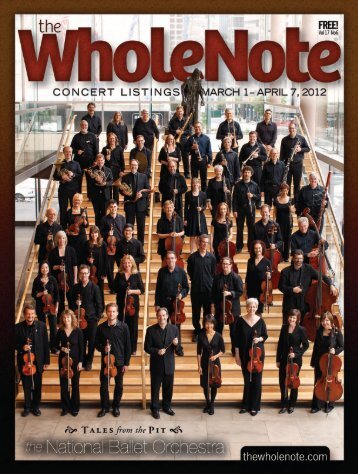

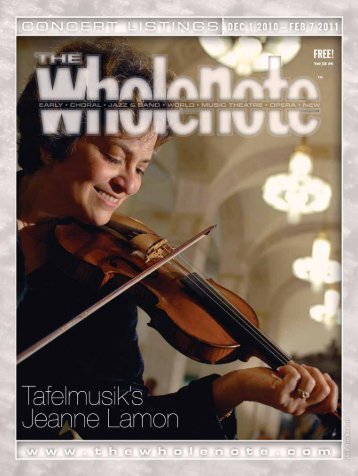

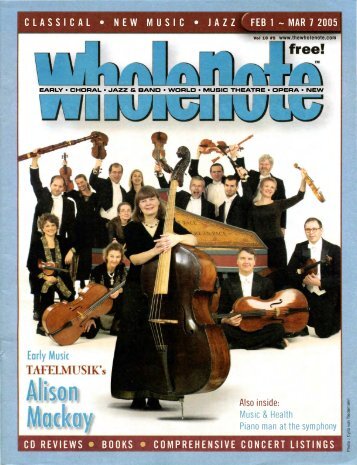

FEATURE From left to right: Dominic Teresi, bassoon (seated); Elisa Citterio, violin (seated); Thomas Georgi, violin (standing, dark tie); Allen Whear, cello (seated); Marco Cera, oboe (standing); John Abberger, oboe (seated); Julia Wedman, violin (seated); Patricia Ahearn, violin (seated); Cristina Zacharias, violin (standing); Brandon Chui, viola (standing, blue tie); Geneviève Gilardeau, violin (seated); Patrick Jordan, viola (standing, yellow tie); Chris Verrette, violin (seated); Charlotte Nediger, harpsichord (seated) CYLLA VON TIEDEMANN To Boldly Go Tafelmusik’s Elisa Citterio DAVID PERLMAN It’s not always a good idea, sitting down for only your second chat with someone, to start off by reminding them of exactly what they told you the first time round, especially if, as in this case, 18 hectic months have elapsed between conversations. But this time it worked out just fine. “In May 2017, the last time we talked,” I reminded Elisa Citterio, Tafelmusik’s music director, “you told me that you were hoping for life here to be, perhaps more busy, but less crazy, than before, and I’d like to come back to that. But you also said something very interesting about repertoire, and this is where I’d like to start. You said ‘We can’t live and die by one hundred years of [Baroque] repertoire. We are strings, two oboes, bassoon and continuo, so there are limits to the core repertoire available, and so it’s important for an orchestra like Tafelmusik to touch different periods, to educate the ear. Period playing can lead to illuminating performances of a much wider range of music – Haydn, Schumann, Brahms, Verdi. Period playing can strip away the denseness of the 19th-century sound. You get to listen for different things.” In May 2017, we had squeezed in a hastily arranged interview in The WholeNote office three months before she officially took the Tafelmusik reins for a first season that was already significantly cut 8 | March 2019 thewholenote.com

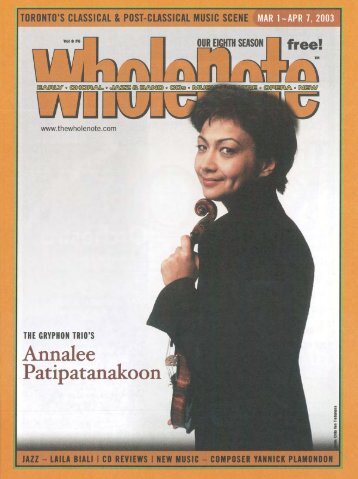

and dried in terms of repertoire. This time we were poring over the details of a 2019/20 season, about to be announced, that will, for better or for worse, be seen as well and truly hers. “When I took on this role” she said, “I left La Scala Theatre where I had been playing for many, many years, all kinds of repertoire; at at the same time, I was playing a lot of Baroque music with other ensembles. So my whole life has been divided between different repertoire, and in my personal experience I can say absolutely that each piece of the picture connects to another one. I can’t say that playing Brahms and Wagner made coming back to Baroque music easier or more difficult. But I have to say I am curious to see how it would be, in the other direction, if musicians in conservatories were trained from early music forward, instead of the other way around.” Her own training, she freely admits, was not the way she would like things to be. “Like most musicians,” she says, “I did things in reverse. I was trained to play caprices from the 18th and 19th century, and concertos of the 19th and 20th century, before going back in time to Mozart and eventually Bach. So it was a lot of jumping around and more focused on technical issues than on musical essentials.” It was only when she started Baroque violin, she says, that she started to connect things musically, because of the way Baroque violin practice was inextricably connected to imitation of the human voice – “to pronunciation, to consonants and vowels, to syntax. Musicians playing violins, cornettos, had to try to imitate the voice, so this changes fundamentally the way one approaches technique.” Going back to these roots, as far back as madrigals, she says, began to influence her modern playing in profound ways, day after day and step by step. It wasn’t a magic formula or shortcut though. Finding her way back to classical and Romantic repertoire took a lot of study all over again. But the changes in her playing were fundamental. “Out of it all,” she says, “what I trusted, what I still trust, is that a Baroque orchestra has a sort of mission; it is unlike modern orchestras approaching Baroque repertoire, where the results might sound nice, but there is still something missing, because they simply don’t have the right instruments. Some things are fundamental to Baroque music that can only be achieved with gut strings and with historical wind instruments based on the voice.” And just because there’s an argument to be made that a modern orchestra can’t travel back in time, it doesn’t mean that the reverse argument applies. After all, modern orchestras used gut strings right up to the time when, grisly fact, world wars saw the end to a reliable supply of gut strings, with the commodity commandeered for sutures. “So, Wagner was writing for orchestras using gut strings,” she says. “And at La Scala we played operas at historically accurate pitch … I feel that if Tafelmusik does not take what we do to the limit, the edge of where we can go, not as a novelty, but consistently, with a process to arrive there, it would be a pity. I think we can really give something new for this music. We are not the first, I am not saying that. But we are one of the few. I have played with orchestras around the world and I can say that Tafelmusik can do great and huge work on this kind of music. But step by step.” Just as finding her way back to classical and Romantic repertoire took a lot of study all over again for Citterio, the coming season’s excursion into the 19th century is not going to be a picnic for the orchestra. “It will be work,” she says, “and we will workshop for it. But Tafelmusik musicians are well informed, so that is a big start. We will concentrate only on the repertoire we are going to play in the coming season, but it is still a lot. For example, the way to shift among positions on the violin alters over the years. In Vivaldi a shift should leave a note as cleanly as possible. In the Romantic repertoire I am trying to connect the voice with a portamento going up and down; also rubato is quite different in the different periods; and the strokes are different; and we have many different kinds of accents that we have to know how to read, because earlier an accent had a different meaning. So this workshop will be really to understand how to work on these technical issues together. And also how to deal with these busy scores, because Tchaikovsky and Brahms wrote a lot on their scores! If you look at a Castello or Fontana score, then at Brahms, the world has changed totally, from nothing to everything.” Thursday, March 14 at 8pm LAFAYETTE AND SAGUENAY QUARTETS 4 + 4 = Octets with two outstanding Canadian quartets Tuesday, April 2 at 8pm HILARIO DURÁN AND FRIENDS with Roberto Occhipinti, bass, Mark Kelso, drums, Annalee Patipatanakoon, violin, and Roman Borys, cello See our 2019-2020 season at www.music-toronto.com 27 Front Street East, Toronto Tickets: 416-366-7723 www.music-toronto.com thewholenote.com March 2019 | 9

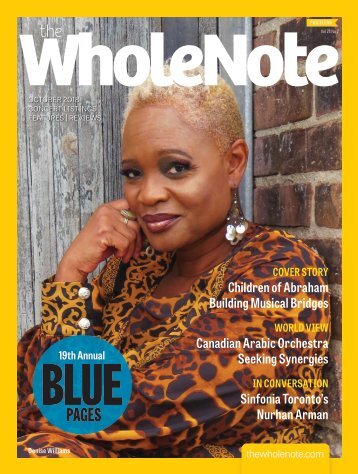

- Page 1 and 2: PRICELESS Vol 24 No 6 MARCH 2019 CO

- Page 3 and 4: 2018/19 Season Masaaki Suzuki, gues

- Page 5 and 6: 2406_MarchCover.indd 1 PRICELESS Vo

- Page 7: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Somethi

- Page 11 and 12: KOERNER HALL 10 th ANNIVERSARY 2018

- Page 13 and 14: Canadian composer Norma Beecroft (b

- Page 15 and 16: FEATURE ALEX PAUK’S ESPRIT WAVE A

- Page 17 and 18: KEVIN LLOYD Esprit’s Ontario Reso

- Page 19 and 20: ´ Kopernikus, Banff Centre for the

- Page 21 and 22: Melody McKiver improvising in Jumbl

- Page 23 and 24: Beat by Beat | Classical & Beyond C

- Page 25 and 26: !! MAR 10, 2:30PM: Bradley Thachuk

- Page 27 and 28: sound out of the hand drums, while

- Page 29 and 30: contemporary storytelling. Looking

- Page 31 and 32: Beat by Beat | Choral Scene Giving

- Page 33 and 34: fans should hurry and get tickets.

- Page 35 and 36: An agency of the Government of Onta

- Page 37 and 38: every once in a while they bring in

- Page 39 and 40: August 20, 1942, at age 19, Murray

- Page 41 and 42: 1066 Dunbarton Rd, Pickering. 647-3

- Page 43 and 44: Richardson-Schulte: GO! for Orchest

- Page 45 and 46: Letter”; Mendelssohn: Octet in E-

- Page 47 and 48: ●●8:00: Etobicoke Philharmonic

- Page 49 and 50: Good Friday. Dubois: The Seven Last

- Page 51 and 52: .25-.25(dinner/brunch & show

- Page 53 and 54: Church, 49 Queen St. N., Kitchener.

- Page 55 and 56: Society. In Concert. Dmitri Kotrana

- Page 57 and 58: ook by Terrence McNally. Theatre Au

- Page 59 and 60:

newer musicians to showcase their c

- Page 61 and 62:

●●Mar 18 1:30: Miles Nadal JCC.

- Page 63 and 64:

When you look at your childhood pho

- Page 65 and 66:

Colin Story inside his hut a number

- Page 67 and 68:

2019 SPECIAL FOCUS SUMMER MUSIC EDU

- Page 69 and 70:

●●Canadian Opera Company Summer

- Page 71 and 72:

Deadline: Registration open; early-

- Page 73 and 74:

12 through adult who have had a yea

- Page 75 and 76:

albeit not in the Schoenbergian man

- Page 77 and 78:

The American composer Paul Lombardi

- Page 79 and 80:

D-flat Major, Op.10 has Prokofiev a

- Page 81 and 82:

institution’s premier vocal ensem

- Page 83 and 84:

Stas Namin - Centuria S-Quark Symph

- Page 85 and 86:

Heiser is a beautiful and accomplis

- Page 87 and 88:

Snowghost Sessions, released near t

- Page 89 and 90:

aggressive, fun and solidly groovin

- Page 91 and 92:

the tenor saxophonist’s heartrend

- Page 93 and 94:

THIS EVENT IS FREE TO SUBSCRIBERS!

- Page 95 and 96:

or the Austrian Georg Friedrich Haa

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...