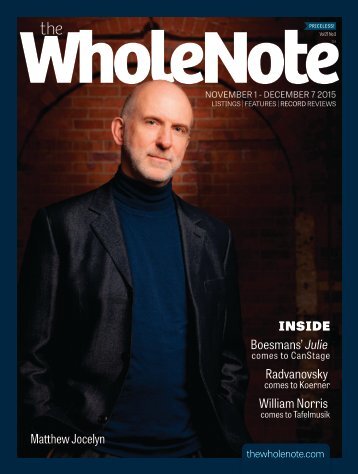

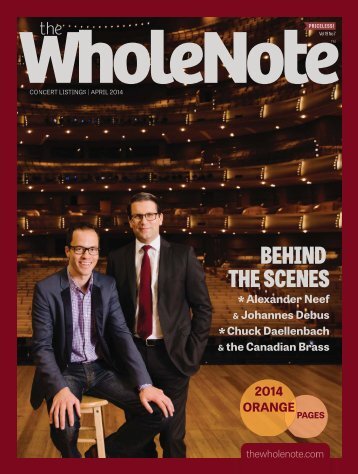

Volume 25 Issue 5 - February 2020

- Text

- Composer

- Performing

- Orchestra

- Arts

- Theatre

- Musical

- Symphony

- Jazz

- Toronto

- February

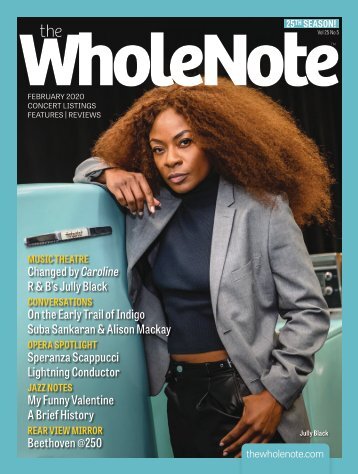

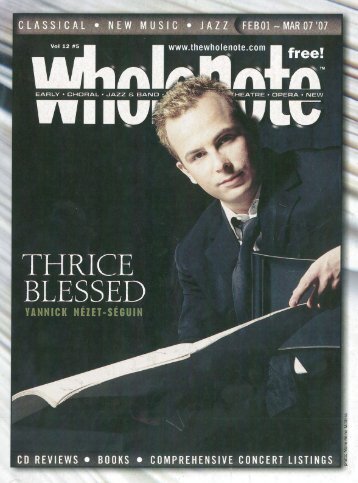

Visions of 2020! Sampling from back to front for a change: in Rearview Mirror, Robert Harris on the Beethoven he loves (and loves to hate!); Errol Gay, a most musical life remembered; Luna Pearl Woolf in focus in recordings editor David Olds' "Editor's Corner" and in Jenny Parr's preview of "Jacqueline"; Speranza Scappucci explains how not to reinvent Rossini; The Indigo Project, where "each piece of cloth tells a story"; and, leading it all off, Jully Black makes a giant leap in "Caroline, or Change." And as always, much more. Now online in flip-through format here and on stands starting Thurs Jan 30.

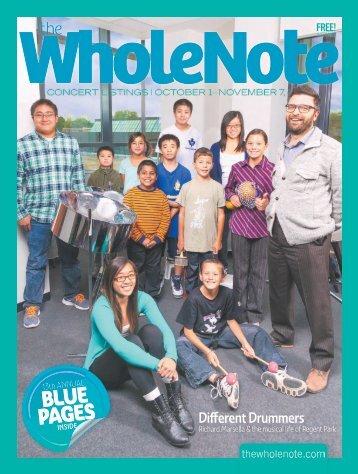

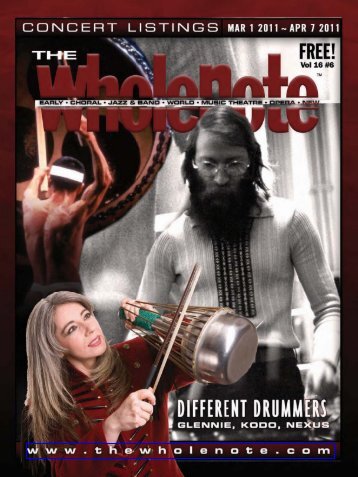

NEXUS members in the

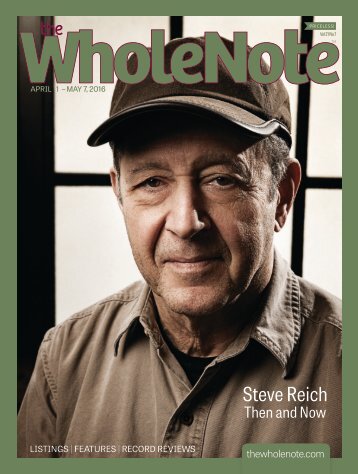

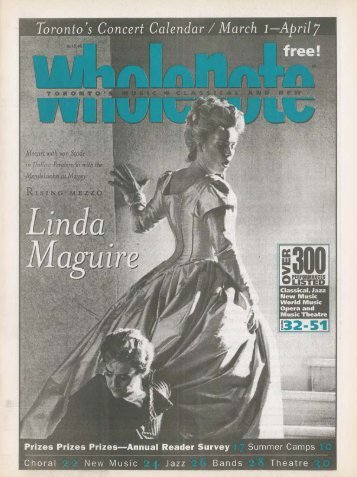

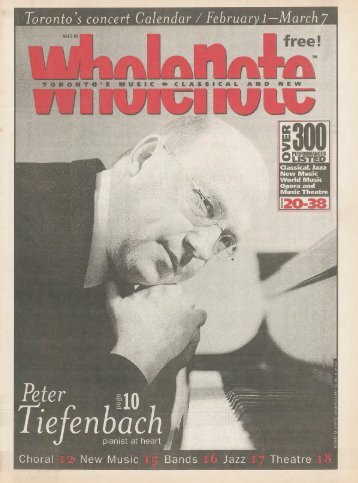

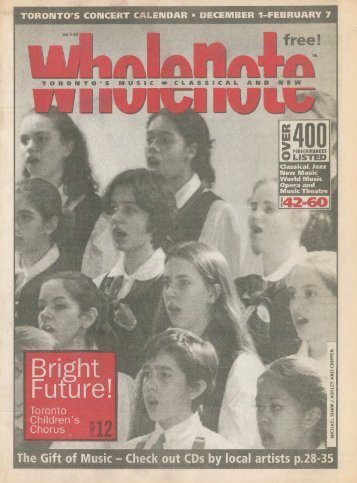

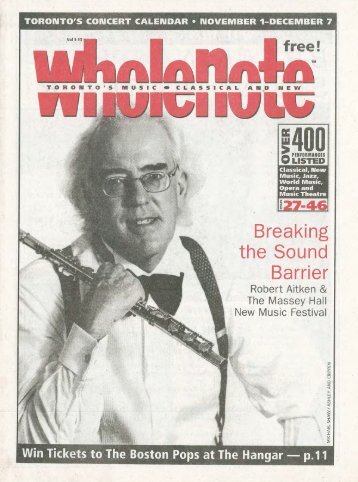

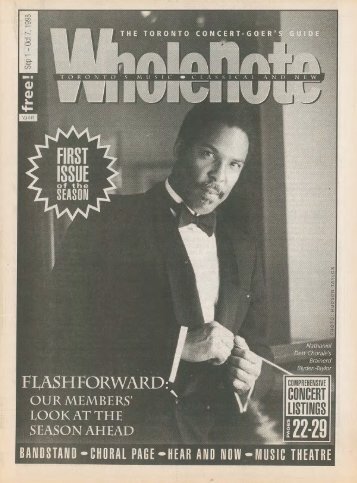

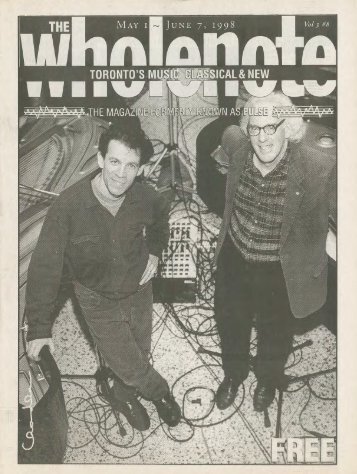

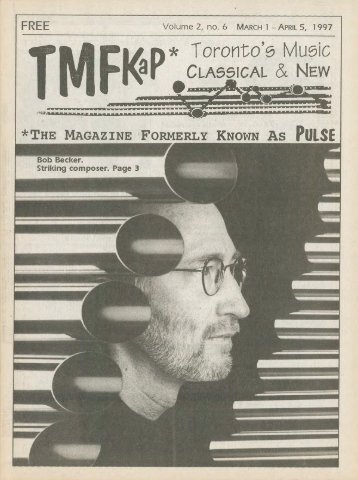

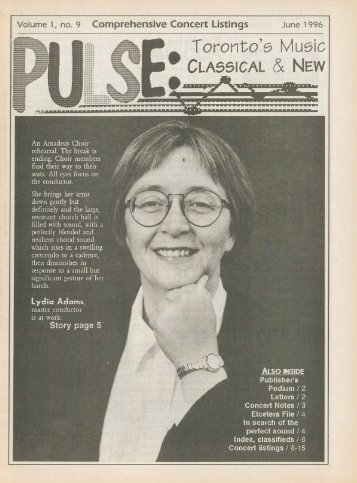

NEXUS members in the recording studio, 1986, (left to right): Bill Cahn, John Wyre, Bob Becker, Russell Hartenberger, Robin Engelmann. Blending musical cultures Before touching on those four works, though, I’d like to explore the musical journey Becker has taken to arrive at this point in time. Some of the first compositions of his I heard, Lahara (1977) and Palta (1982), employed an explicitly multicultural approach, cannily morphing elements of Western military-based rudimental drumming with North Indian classical (Hindustani) idioms: tabla drumming and raga. In Hindustani concerts the role of tabla drumming is primarily as a time keeper, though on occasion it transforms into a dialogue between the tabla and the main melodic performer. Becker made use of such tabla playing in his “melodic” writing for the snare drum in Palta, implementing in the music a convincing multicultural music aesthetic. Traces of influences from musical minimalists like Steve Reich, as well as his extensive percussion keyboard work with NEXUS, were also evident stylistic elements. Becker’s world music education began in earnest at Wesleyan University. He spent four years in its world music program studying with several masters of Javanese, Indian and Ghanaian musics. “Probably the most significant teachers for me at that time were my tabla teacher Sharda Sahai and my African drum teacher Abraham Adzenyah,” noted Becker in Percussive Notes. As for his 49-year association with NEXUS, Becker once candidly reflected that it “is far more than a musical ensemble of which I happen to be a member. It has been a support group, a forum for composition and experimentation, an educational resource, a financial cushion and an extended family, with all of the joy, sadness, love and craziness that ‘family’ implies.” The spoken, written and sung word I asked to meet with Becker at his Toronto home to get a better sense of his music and upcoming concerts. He cordially obliged on the brink of the 2019 Holiday season. I first asked how he would characterize the (perhaps surprising to some) selection of his songs with instrumental accompaniment his ensemble is presenting in February. “I suppose we could call them chamber songs or vocal chamber music,” he replied. “The poetry which forms the lyrics is important in these works. In fact, my engagement with the written and spoken word in music performance goes back at least to the collaborations NEXUS had with the distinguished Canadian poet Earle Birney (1904 -1995). We did several concerts with him in Toronto, perhaps the first of which was at York University in the early 1970s. Raga and tala in Becker compositions Raga is a central concept in Indian music, yet there’s no simple way to describe it in Eurocentric music tradition terms. As I understand it, ragas fall somewhere on the continuum between melody and scale. They can further be characterized as separated by scale, lines of ascent, descent and transilience, emphasized notes and register, modal contour, by intonation and ornamentation. I asked Becker which of the four works on the February concerts is informed by raga (commonly spelled “raag” in Hindustani music). “All the works on my February concerts are informed by raag,” Becker stressed. “Mudra (1990) also references Indian music. It was composed for the Toronto choreographer Joan Phillips for her dance work UrbhanaMudra. A 15-minute music suite, Mudra led me to develop the musical language I still use. Over time I’ve found this idea had legs.” In his article Finding a Voice (in The Cambridge Companion to Percussion, 2016) Becker delineates his idiosyncratic journey incorporating notions of raga into his compositions. “The exquisitely ornamented and melismatic melodic phrases of Indian music,” he wrote, “imply no harmonic direction and hold no cadential tension to be resolved by real or implied triadic progression. … However, my experience was quite different. For someone born and raised in a culture saturated with music based on chord progressions, it is probably inevitable that the mind will supply imagined harmonies when hearing monophonic or heterophonic melodies.” Music On The Moon, commissioned by Esprit Orchestra, is a 1996 Becker chamber orchestra work informed by raag Chandrakauns. “Chandrakauns has five tones per octave,” Becker observed. “By playing around with these tones, I discovered that stacked vertically they create an ambiguous harmonic space. From a Western perspective, I could construct chords with these stacked notes. I was able to derive some surprisingly elaborate structures, including the matrix of four nine-tone scales currently employed in my music, from this conceptual notion.” Our cover story, March 1997 “The Magazine Formerly Known As Pulse” Becker describes this set of principles as “a comprehensive, consistent and personal methodology for handling both melodic and harmonic construction. In that way I explored raga as a source of melody and harmony. As for instrumentation, I usually score for keyboard percussion instruments such as vibraphone, marimba and piano as in Cryin’ Time. In my music, the piano is treated like a percussion instrument while I often treat the percussion instruments as keyboards.” Bob Becker Ensemble Becker has been a veteran member of several prominent Canadian and American percussion-based ensembles. When (and why) did he think to establish his own group? “In the mid-1990’s I formed an ensemble to exclusively perform my music,” he replied, “taking a page from the Steve Reich Ensemble, of which I’m a longtime member. I learned much from Steve in how to combine the roles of performer and composer. His ensemble works 14 | February 2020 thewholenote.com

with an enigmatically dense chord on the piano, while the keyboard percussion supplies low tremolos and arpeggiated figures. Never in Word (1998) is also scored for soprano, piano and keyboard percussion. Its lyrics are drawn from a short poem by the American author Conrad Aiken (1889-1973), long one of Becker’s favourite poets, one of series of 96 poems under the collective title Time in the Rock (1932, 1953). Aiken begins his poem with a comparison of the merits of music and poetry. Becker’s vocal melody moves between cantabile lines and disjunct leaps, the instruments effectively echoing, underpinning and contesting it. The remaining two songs on the February program represent Becker’s most recent work. To Immortal Bloom (2017) is for soprano, vibraphone, piano and cello, with lyrics also derived from Aiken, here poem XXI of Preludes for Memnon (1931). “The obvious musical and numerical references, as well as a feeling of reverie in the concluding imagery, were the inspiration for the musical setting,” writes Becker. Clear Things May Not Be Seen (2018) ups the vocal and instrumental ante. Scored for two soprano soloists plus string quartet, clarinet, bass clarinet, marimba and vibraphone, the song’s lyrics once more borrow from Aiken’s epic cycle Time in the Rock – this time from three different poems. At 13 minutes it also clocks in nearly twice as long as To Immortal Bloom, reflecting Becker’s expanding compositional ambitions. Becker has thought long and deep about what it means to be both a composer and performing musician today. “… Am I a percussionistcomposer or a composer-percussionist?” he asks in Finding a Voice. “Although I still may be in transition from the former, the principles and rules I need to function as the latter are firmly in place in my work,” begins his answer, concluding with, “If percussionists recognize me to be a composer, and composers consider me to be a percussionist, perhaps that is the best of both worlds. Bob Becker, Six Pianos (1973) and Music for 18 Musicians (1976) are seminal examples of that [communal creative] process in action. The rehearsals and compositional process went hand in hand, taking a number of months for the full composition to slowly emerge, section by section.” Is there ever a tension between Becker’s career as a percussionist and a composer? “I often play in my own works,” he reflected, “for instance, I’m playing vibes in the February concerts, doing double duty. I’ve always wanted to be in the music. On the other hand, for over 20 years I was on the road as a percussionist for more than half the year and I found it difficult to compose on the road. I need to be ‘in the zone,’ in a dedicated space, when composing.” Double career of the percussionist-composer It seems to me, I observed to Becker, that in the Western world the double career of percussionist-composer is a particularly 20th-century phenomenon. Which notable composers who also played percussion have been Becker influences? “I can think of John Cage, Lou Harrison, Harry Partch and the late Michael Colgrass,” he quickly replied. “Of course we should also add Steve Reich, who not only studied Western percussion but also cited West African and Balinese percussion as early influences. Also significant in this context is that Steve was always interested in using musicians with non- Western and early [Western] music backgrounds.” “In Finding a Voice I discuss composing for percussion,” Becker added. “I’ve kept writing music in a continuously developing manner, building and developing on previous works consciously, as I saw Steve Reich and Philip Glass doing. In my quest as a composer I learned a lot from them…” February concerts: the compositions Cryin’ Time (1994) scored for soprano solo, vibraphone, marimba and piano features lyrics adapted from a poem by Canadian artist Sandra Meigs. It tells the troubling story of a young mother who accidentally drops her baby into a deep river canyon; yet it’s told in an anomalously matter-of-fact narrative style redolent of a hurtin’ country song. “I wanted my music to play even more on this ambiguity, which was the reason for adapting the text (done with the artist’s permission),” writes Becker in his program notes. The eight-minute work closes ominously BULLET TRAIN / Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com. A dramatic reading of Madeleine Thien’s powerful short story, paired with the world premiere of Alice Ping Yee Ho’s avantgarde tribute to Yoko Ono. FEBRUARY 21 & 22, 8:00 P.M. AKI STUDIO, DANIELS SPECTRUM WITCH ON THIN ICE thewholenote.com February 2020 | 15

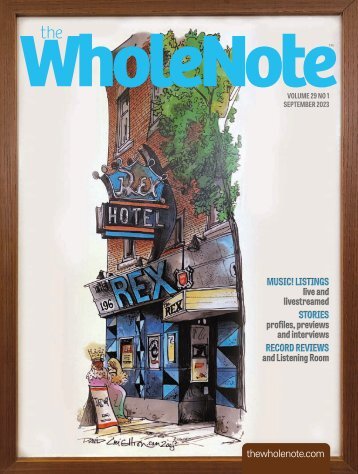

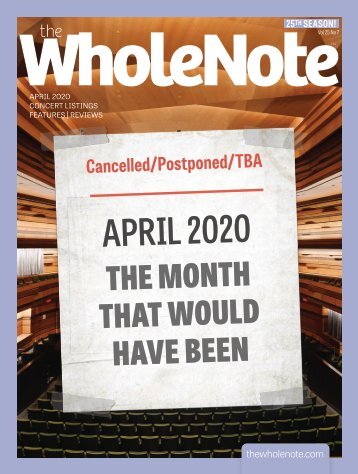

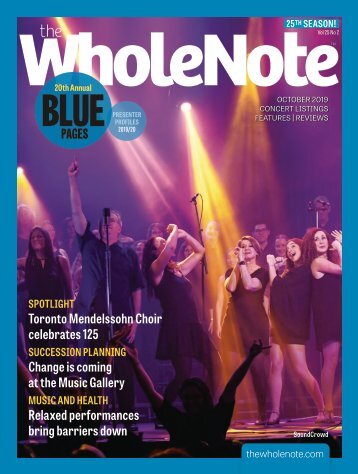

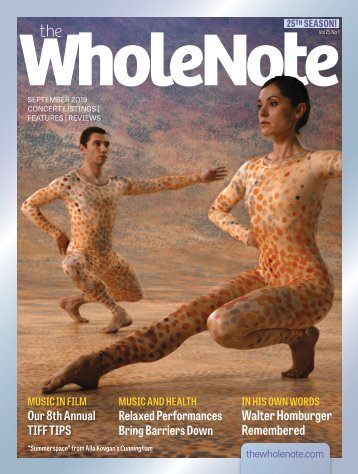

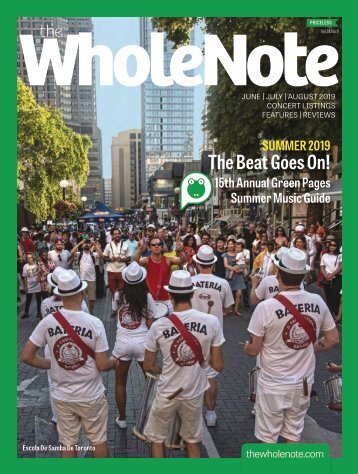

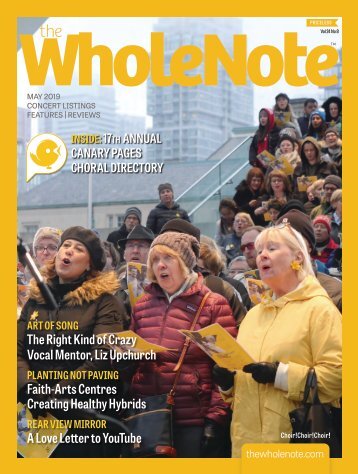

- Page 1 and 2: 25 th SEASON! Vol 25 No 5 FEBRUARY

- Page 3 and 4: 2019/20 Season THE INDIGO PROJECT D

- Page 5 and 6: 2505_Feb2020_Cover.indd 1 2020-01-2

- Page 7 and 8: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Plenty

- Page 9 and 10: BRIGHTEN YOUR FEBRUARY with BRILLIA

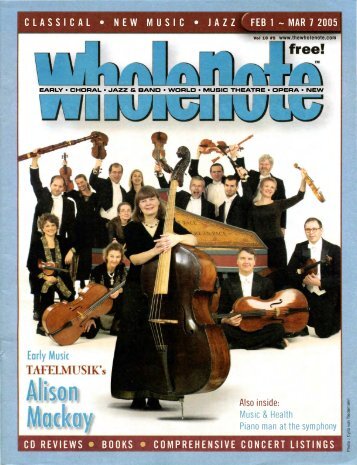

- Page 11 and 12: Alison Mackay and Suba Sankaran “

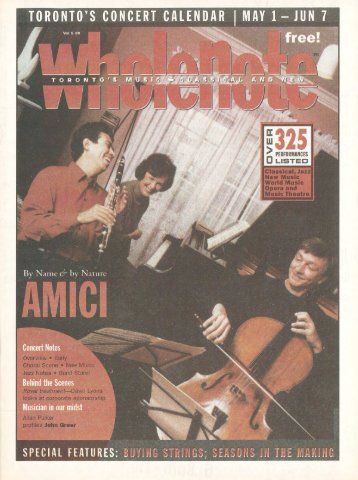

- Page 13: WORLD VIEWS BEST OF BOTH WORLDS Com

- Page 17 and 18: orchestra has to be refined, always

- Page 19 and 20: UOFTFACLTYOFMUSIC DANIEL FOLEY Robe

- Page 21 and 22: KOERNER HALL 2019.20 Concert Season

- Page 23 and 24: Clockwise from top left: Frank Sina

- Page 25 and 26: SIM CANETTY-CLARKE WILLEKE MACHIELS

- Page 27 and 28: !! FEB 21, 8PM: The Royal Conservat

- Page 29 and 30: RUTH WALZ Peter Sellars (left) and

- Page 31 and 32: A previously unreleased conceptual

- Page 33 and 34: JESSICA GRIFFIN Ola Gjeilo relevant

- Page 35 and 36: eflecting how there is always someo

- Page 37 and 38: moment when she has to split with h

- Page 39 and 40: accommodate the trumpet mouthpiece.

- Page 41 and 42: ●●Summer@Eastman Eastman School

- Page 43 and 44: Hall, 651 Dufferin St. 437-233-MADS

- Page 45 and 46: ●●2:00: Rezonance Baroque Ensem

- Page 47 and 48: Thomson Hall, 60 Simcoe St. 416-872

- Page 49 and 50: and Gelato, 1006 Dundas St. W. 647-

- Page 51 and 52: Sankaran, choral director. George W

- Page 53 and 54: Cumberland. Chaucer’s Pub, 122 Ca

- Page 55 and 56: C. Music Theatre These music theatr

- Page 57 and 58: Russell Malone Anthony Fung George

- Page 59 and 60: Clubs & Groups ●●Feb 09 2:00: C

- Page 61 and 62: February’s Child is Beverley John

- Page 63 and 64: to name but a few (i.e. the ones I

- Page 65 and 66:

somm-recordings.com) is an excellen

- Page 67 and 68:

having unwittingly fathered an ille

- Page 69 and 70:

VOCAL Vivaldi - Musica sacra per al

- Page 71 and 72:

production from Sardinia’s Teatro

- Page 73 and 74:

the playing is elegant and the ense

- Page 75 and 76:

composer. His career spanned almost

- Page 77 and 78:

JAZZ AND IMPROVISED Taking Flight M

- Page 79 and 80:

several albums which push the bound

- Page 81 and 82:

Creation - such as The Nomad and Ma

- Page 83 and 84:

REMEMBERING Remembering ERROL GAY F

- Page 85 and 86:

TS Toronto Symphony Orchestra RACHM

- Page 87 and 88:

without a net, the artist lacking a

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...