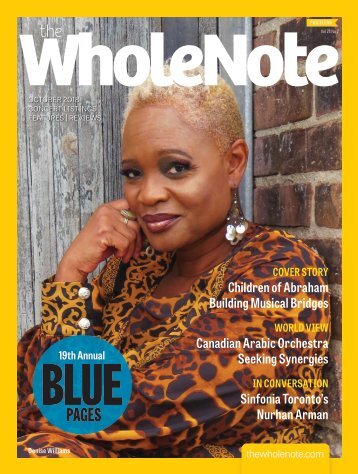

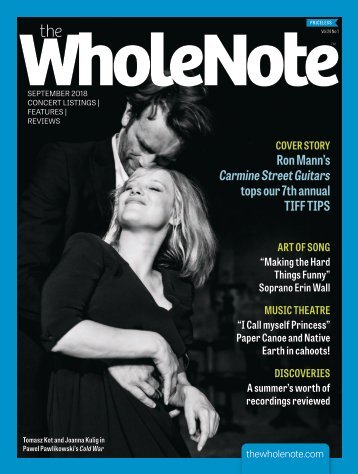

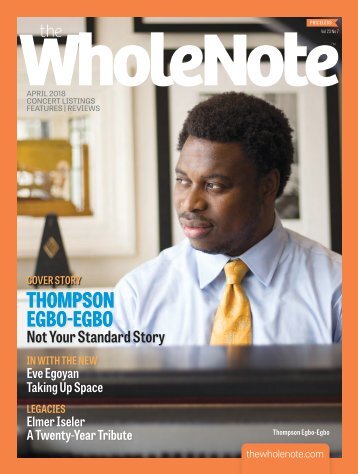

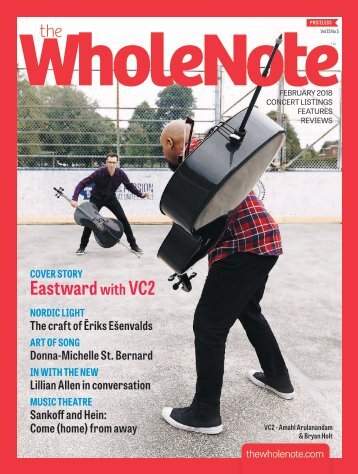

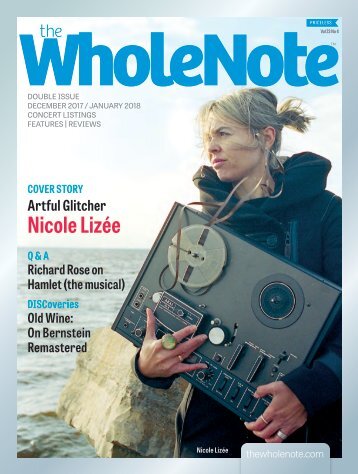

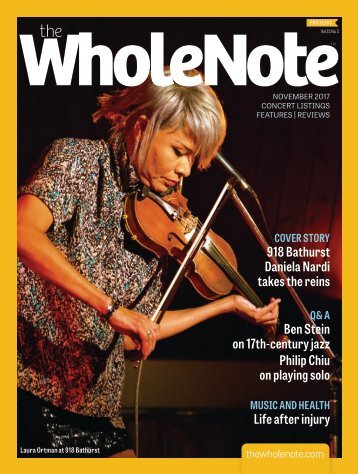

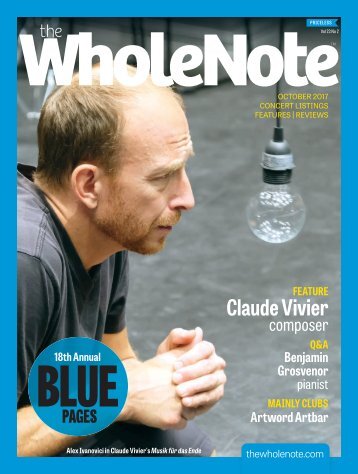

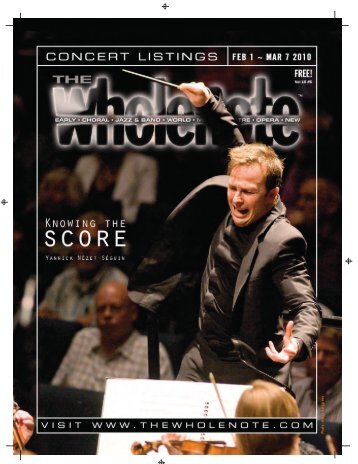

Volume 25 Issue 5 - February 2020

- Text

- Composer

- Performing

- Orchestra

- Arts

- Theatre

- Musical

- Symphony

- Jazz

- Toronto

- February

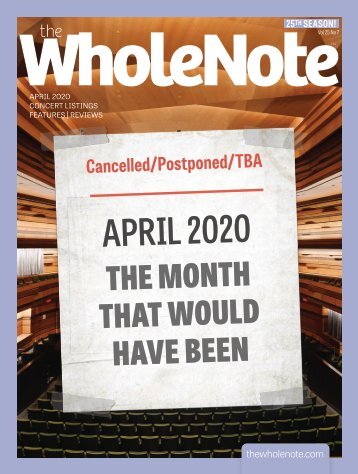

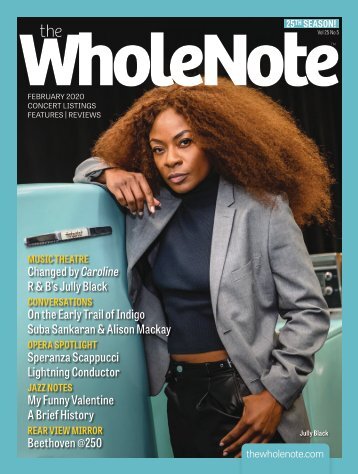

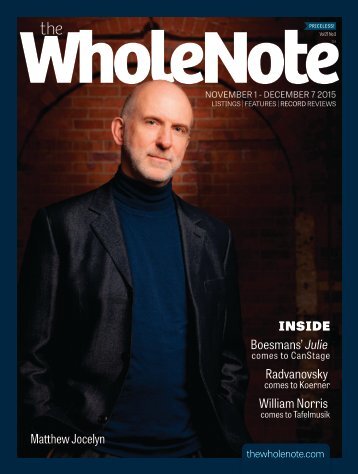

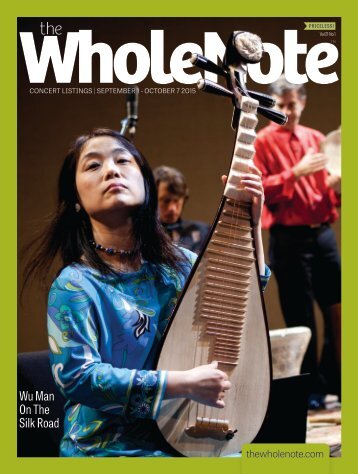

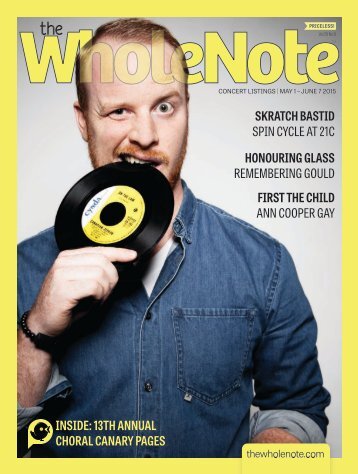

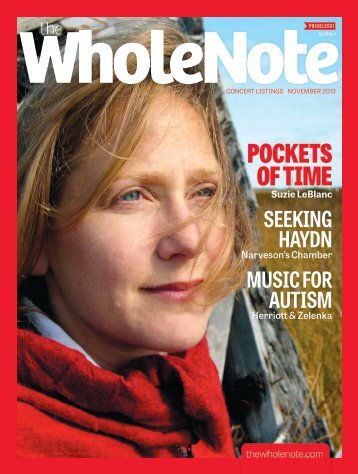

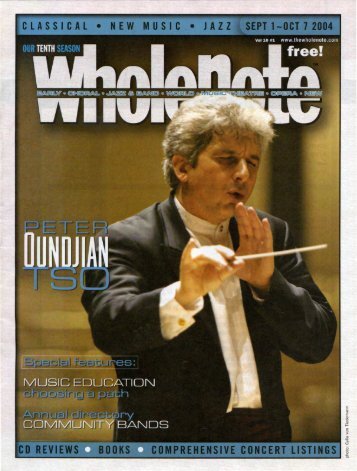

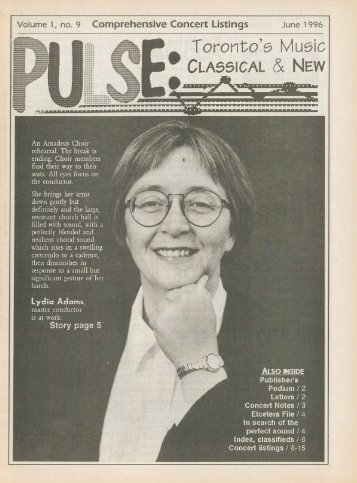

Visions of 2020! Sampling from back to front for a change: in Rearview Mirror, Robert Harris on the Beethoven he loves (and loves to hate!); Errol Gay, a most musical life remembered; Luna Pearl Woolf in focus in recordings editor David Olds' "Editor's Corner" and in Jenny Parr's preview of "Jacqueline"; Speranza Scappucci explains how not to reinvent Rossini; The Indigo Project, where "each piece of cloth tells a story"; and, leading it all off, Jully Black makes a giant leap in "Caroline, or Change." And as always, much more. Now online in flip-through format here and on stands starting Thurs Jan 30.

Beat by Beat | Jazz

Beat by Beat | Jazz Notes My (Not So) Funny Valentine A Brief History STEVE WALLACE WILLIAM P. GOTTLIEB February is the shortest month of the year, which is merciful, because it is also surely the bleakest. By the time it rolls around, winter has been with us for what seems like an eternity, with still plenty to come. The festivities of Christmas and Hanukkah are a distant memory and the bloom is off the rose of the new year. Of course there’s Valentine’s Day on February 14, but even that special day of celebrating romance is a mixed blessing to some, and many have sworn off it. Those not blessed with a partner, or who have recently lost one, find it lonely and painful. And even many with partners find it an empty and contrived occasion filled with pressure, a cash-in day for florists, candy makers, card companies, swanky restaurants and the like. Despite these misgivings, I thought it might be interesting to explore the history of the song most associated with the day, My Funny Valentine, one which has become an essential part of jazz history and its repertoire, and also one which has been much misunderstood. It has been recorded over 1,600 times by more than 600 artists, both instrumentally and vocally, and is permanently associated with Frank Sinatra, Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker and Miles Davis, among others. It was written in 1937 by perhaps my favourite songwriting team, Richard Rodgers and lyricist Lorenz Hart. Rodgers had the supreme gift of writing simple, pure melodies which stuck in the ear and which he would often flesh out with more interesting chords. And Hart stood alone as a lyricist; his words had great wit and charm, ironic humour, interior rhythm and often plumbed emotional depths worthy of poetry. As a team, they were incomparable; Rodgers’ later songs with lyricist Oscar Hammerstein are far less successful simply because the words don’t work nearly as well. (As an aside, this didn’t stop Cole Porter’s “beard” wife, Linda Lee Thomas, from asking pointedly of Rodgers & Hart after meeting them at a party: “Two guys, to write one song!?”) Richard Rodgers (left) and Lorenz Hart My Funny Valentine was written for the musical comedy Babes In Arms, which opened in New York on April 14, 1937 and ran for 289 performances until December of that year. Because of its title, My Funny Valentine has always been associated with Valentine’s Day, but that’s something of a misconception, as its original use in the show is more literal: it is sung by a female character to the male lead whose name is Valentine “Val” La Mar, and it’s only in the closing line – “each day is Valentine’s Day” – that the day itself is mentioned. It’s a love song, yes, but not a typical one. Rather than extolling the virtues of the paramour in typical “moon in June” fashion, the words address the foibles of the object of affection, while leaving no doubt that Valentine is loved in spite of these obvious flaws – “Your looks are laughable, unphotographable. Yet you’re my favourite work of art.” And later, “Is your figure less than Greek? Is your mouth a little weak?” And finally, “Don’t change a hair for me, not if you care for me.” The irony at work here is typical of Lorenz Hart, indeed many have commented that these words are a love song to himself. To put it mildly, Hart suffered from low selfesteem and was a somewhat desperate soul: short, unattractive, a closeted gay who suffered from severe addictions to both drugs and alcohol, given to nasty outbursts yet with the soul of a poet. The emotional ambiguity of the lyrics are echoed in the musical content of the song, which begins with a stark and sombre melody in C minor with a chromatically descending bass line down from C. (It was–somewhat rare for Rodgers to work in minor.) The second system remains in C minor but the melody shifts to imply the relative major of E-flat. The middle section, or bridge, remains in E-flat major and is bright in mood, but returns to C minor for the closing system, which has an extra four bars. The first two bars of this last 12 are identical to the first two bars of the song – darkly minor in melody and harmony – then switch to major melody with minor harmony underneath. This leads to the song’s climax, “Stay little Valentine, stay,” with the word “stay” landing on a sustained, high E-flat against a C minor chord, which gradually resolves to an E-flat major chord – “Each day is Valentine’s Day.” The lyrics and the music form an organic whole, and the layered complexity of both explains the attraction of the song for singers and instrumentalists alike through the years, yet it was some time before the song became the ubiquitous standard it is now. Perhaps it was too dark and poignant, but at any rate it was left out of the 1939 movie version of Babes In Arms, featuring Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, which spawned the “Hey kids, we could put on a show!!” genre of movies they often made together. There were only a few recordings of it made in the 1940s, but a revival of the show in the early 50s spawned a flurry of great recordings of the song – perhaps audiences 22 | February 2020 thewholenote.com

Clockwise from top left: Frank Sinatra, Chet Baker & Gerry Mulligan, Lee Wiley, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan were more ready for it. Frank Sinatra recorded it for Capitol just as his career was hitting stride again after hitting the doldrums in 1949-51. The “Poet Laureate of Loneliness” certainly captured all of the song’s vulnerability and tenderness and his nuanced version did a lot to put the song on the map with both audiences and musicians. Sinatra’s rendition of it in the hit 1957 musical movie Pal Joey didn’t hurt either, but by that time there were several celebrated jazz recordings of the song. As has so often been the case, it is these jazz interpretations which have rendered the song immortal, starting with Gerry Mulligan’s 1953 version by his pianoless quartet featuring Chet Baker, which came hard on the heels of the Sinatra record. This quartet achieved instantaneous and widespread success, and Mulligan’s recording of Valentine was both a boost to this and to the tune itself. His restrained, lyrical arrangement makes brilliant use of the bass in filling out the harmony in the absence of piano and as always, the melodic interplay between him and Baker is ravishing. In 2015, Mulligan’s 1953 version of it (he would revisit it several more times) was inducted into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress for its “cultural, artistic and/or historical significance to American society and the nation’s audio legacy.” The first Mulligan quartet’s success ended with his imprisonment for narcotics in early 1954, but Chet Baker didn’t miss a beat. He recorded a vocal version of Valentine in 1954 which made him a jazz star forever. His sensitivity toward both the song’s lyric and melody captivated audiences and bestowed on Baker a cult following of James Dean proportions, one which, for better or worse, would remain with him throughout his career. 1954 was the year Miles Davis began moving toward real stardom, leading to the formation of his first great quintet in 1955. Miles first tackled Valentine in a marathon recording session on October 26, 1956, with tenor saxophonist John Coltrane sitting out. He takes a more daring approach to the song, playing the melody for only about five bars before offering some beautiful melodic improvisation, yet he fully captures the song’s mood and possibilities. The track owes a lot to pianist Red Garland’s lyricism and again, it further cemented the reputation of both Davis and this song. Miles played the song often and there is a famous live version from a concert recorded at Lincoln Center on February 12, 1964, with his celebrated second quartet. This version is arresting in both its starkness and abstraction, owing a lot to the harmonic acuity and daring of Herbie Hancock. These are likely the most celebrated jazz recordings of My Funny Valentine, yet there are two others done between the Mulligan and Davis versions which eluded my notice for a long time and which deserve to stand alongside these others. Ben Webster recorded a lovely version on a March 30, 1954 session with Teddy Wilson, Ray Brown and Jo Jones which yielded just four tunes and was released as Music For Loving. Music for loving indeed; a sonic and emotive master like Webster need only play the melody to make you realize what a beautiful song this is. Cornetist Ruby Braff and pianist Ellis Larkins, who excelled as an accompanist in duos, tackled it in 1955 on their celebrated Vanguard album of Rodgers & Hart tunes, 2X2. Braff is as creative with the song in his own way as Miles Davis was in his. This is the first version I’d heard which includes Valentine’s stirring, almost madrigal-like verse, played here by Larkins. It deserves to be better known, but is usually only included by singers, with its oddly appropriate Elizabethan words such as “doth” and “thou” and “thy.” Speaking of duo treatments, Bill Evans and Jim Hall recorded a very fast (the song is generally played as a ballad) version on their 1962 album Undercurrent. The rest of the record is generally lyrical and gentle, but Hall and Evans take the song to the races, it’s by far the most aggressive treatment of the song up to that point. Evans, in very frisky form, states the melody, then offers crunchy, bristling accompaniment to Hall’s guitar solo. Hall returns the favour by breaking into some of the finest 4/4 rhythm guitar ever played, complete with bass lines and drum-like shots. It’s stunning and swings like mad. Hall would revisit the tune at a similarly fast tempo on It’s Nice To be With You, recorded in Berlin in 1968 with Jimmy Woode on bass and Daniel Humair on drums. Hall overdubs a second improvised guitar voice, demonstrating that he had telepathic melodic interplay not only with others, but also when playing with himself, so to speak. These are some of the celebrated instrumental jazz versions which gave the song a permanent place and showed its almost infinite possibilities as a vehicle for improvisation, but I would be remiss if I didn’t mention a couple of vocal versions which stand out among many. Sarah Vaughan recorded it several times but the version on 1973’s Live In Japan is stunning – Vaughan at her sassiest, almost operatic best. Fri. Feb. 21 7 pm goin’ back to mardi gras 2020 TICKETS: $25 Advance tickets & group discounts: standrewstoronto.org Kick-up-your-heels, traditional Mardi Gras street beat music, parade, beads & more! thewholenote.com February 2020 | 23

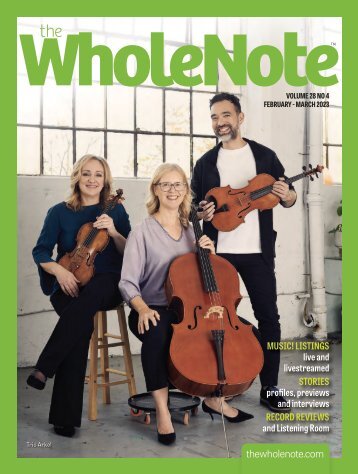

- Page 1 and 2: 25 th SEASON! Vol 25 No 5 FEBRUARY

- Page 3 and 4: 2019/20 Season THE INDIGO PROJECT D

- Page 5 and 6: 2505_Feb2020_Cover.indd 1 2020-01-2

- Page 7 and 8: FOR OPENERS | DAVID PERLMAN Plenty

- Page 9 and 10: BRIGHTEN YOUR FEBRUARY with BRILLIA

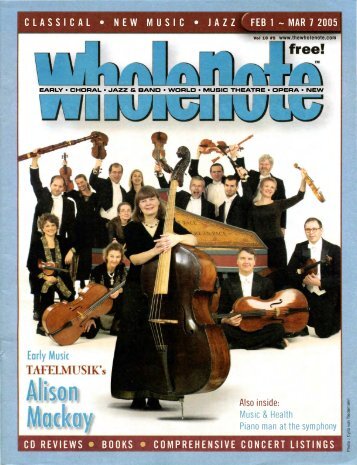

- Page 11 and 12: Alison Mackay and Suba Sankaran “

- Page 13 and 14: WORLD VIEWS BEST OF BOTH WORLDS Com

- Page 15 and 16: with an enigmatically dense chord o

- Page 17 and 18: orchestra has to be refined, always

- Page 19 and 20: UOFTFACLTYOFMUSIC DANIEL FOLEY Robe

- Page 21: KOERNER HALL 2019.20 Concert Season

- Page 25 and 26: SIM CANETTY-CLARKE WILLEKE MACHIELS

- Page 27 and 28: !! FEB 21, 8PM: The Royal Conservat

- Page 29 and 30: RUTH WALZ Peter Sellars (left) and

- Page 31 and 32: A previously unreleased conceptual

- Page 33 and 34: JESSICA GRIFFIN Ola Gjeilo relevant

- Page 35 and 36: eflecting how there is always someo

- Page 37 and 38: moment when she has to split with h

- Page 39 and 40: accommodate the trumpet mouthpiece.

- Page 41 and 42: ●●Summer@Eastman Eastman School

- Page 43 and 44: Hall, 651 Dufferin St. 437-233-MADS

- Page 45 and 46: ●●2:00: Rezonance Baroque Ensem

- Page 47 and 48: Thomson Hall, 60 Simcoe St. 416-872

- Page 49 and 50: and Gelato, 1006 Dundas St. W. 647-

- Page 51 and 52: Sankaran, choral director. George W

- Page 53 and 54: Cumberland. Chaucer’s Pub, 122 Ca

- Page 55 and 56: C. Music Theatre These music theatr

- Page 57 and 58: Russell Malone Anthony Fung George

- Page 59 and 60: Clubs & Groups ●●Feb 09 2:00: C

- Page 61 and 62: February’s Child is Beverley John

- Page 63 and 64: to name but a few (i.e. the ones I

- Page 65 and 66: somm-recordings.com) is an excellen

- Page 67 and 68: having unwittingly fathered an ille

- Page 69 and 70: VOCAL Vivaldi - Musica sacra per al

- Page 71 and 72: production from Sardinia’s Teatro

- Page 73 and 74:

the playing is elegant and the ense

- Page 75 and 76:

composer. His career spanned almost

- Page 77 and 78:

JAZZ AND IMPROVISED Taking Flight M

- Page 79 and 80:

several albums which push the bound

- Page 81 and 82:

Creation - such as The Nomad and Ma

- Page 83 and 84:

REMEMBERING Remembering ERROL GAY F

- Page 85 and 86:

TS Toronto Symphony Orchestra RACHM

- Page 87 and 88:

without a net, the artist lacking a

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...