Volume 9 Issue 6 - March 2004

- Text

- Toronto

- Jazz

- Theatre

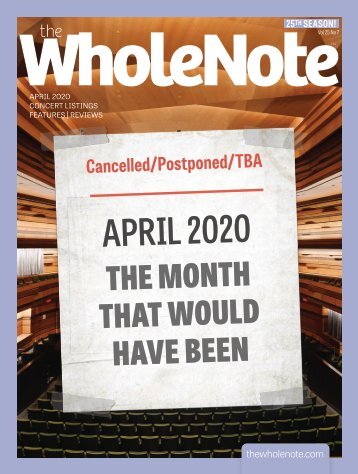

- April

- Musical

- Arts

- Symphony

- Classical

- Orchestra

- Faculty

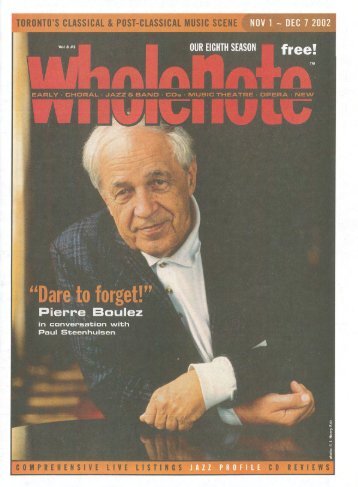

_4,iiil&,MJ;i,,14,fai&,MJ;- AN INTERVIEW WITH Mauricio Kagel KAGEL: The problem of the avant-garde in the sixties was that it tried to be avant-garde at every moment, always the opposite of the rear-guard. In each of us belonging to this curious • BY PAUL STEENHUISEN society of composers, you can Mauricio Kagel is arguably the most prolific and respected Argen- discover traces of conservatism tinean-born composer. On Boulez 's urging, he moved from Buenos that are more-or-less strong. Aires to Cologne in 1957, where he became associated with Stock- The difference in these composhausen and Ligeti, while working at the Electronic Music Studio and ers was how extreme their conattending the Darmstadt Summer Course for New Music. His mu- servatism was. This is very~sic, films, and theatre works break virtually every supposed rule of portant to me - how conservative musical conduct, and leave the receiver with a double-edged impres- was the avant-garde of the·sixsion of both genJle humour and dark madness. A day after the New ties, and how conservative has Music Concerts event that concluded a multi-day Kagel quasijesti- experimental music become toval, I had the opportunity to speak with him about his vast body of day? I could speak about acak d h demic experimental music, but wor ,, an s are an hour of his bright and nervous energy. then I'm talking about killing all STEENHUISEN: I vividly re- STEENHUISEN: It was as of the possibilities that an expericall being at the Concertgebouw though he were asking a ques- ment can have. In an experiin Amsterdam in 1991, witness- tion to the orchestra as well. He ment, the end result is very diffiing the orchestra play a long, was confused. cult to predict. Certain processes thickly orchestrated and strongly are unpredictable, but experimen- Germanic music, your Variation KA

ive, through mostly traditional music notation, at something that is an absolutely non-traditional context?" is an invitation to think about musical performance, and musical language. Many performers are concentrating on the technical field of reproducing the musical score. The musical perception is condemned .to a lower, level, and this is a pity. STEENHUISEN: So you change, and disrupt things to keep everybody super-conscious. KAGEL: Yes. Aware that they are a very complex mechanism. The simplest things can become theatre. A classical example of that would be if you're sitting in a bar, reading a newspaper, and notice that someone is Staring at you. You stop reading the newspaper, and you then look like someone who is reading the newspaper. The same can occur in music. Speaking with performers, I was very happy to learn that this awareness has a function. STEENHl)ISEN: What about the listener? KAGEL: I'm often surprised by how.sensitive listeners are to what is going on in a piece. For example, the public can be very conservative and never want to hear any more dissonance, and so on. But after 50 years of going to concerts, and making concerts, I can tell you that most of the time, the public is not unjust. If you measure minutes, or seconds of applause, you will see that the perception or real importance of the piece has a relative number of seconds. measur¢d in applause. We can look at the opera companies and complain that they are always playing the same 50 operas, but, well, they are the best. Even if they are badly played, eve11 with horrible scenery, even if the staging is impossible, they function, because they are so good that they're very difficult to ruin. STEENHUISEN: You can say that as a composer living in Germany, but here, don't you think that the insistence on those same 50 operas could exclude the creation of another great new one that's being written now? KAGEL: (loudly) No no no, I'm not saying there is no place for the new, I'm not an idiot conservative. I'm telling you MARCH 1 - APRIL 7 2004 "IRONY, AMBIGUITY AND COMEDY end. It's full of magical absurdity. If you have the sensibility to see this, you become very aware of it. The musical world is trying to be very rational because mu ·1 sic itself is inexplicable u and irrationffi al. Music is ~I a rational ::oi discipline thatcommu- ARE MUCH MORE DIFFICULT THAN PATHETIC THINGS" =================== is what something that's related to the makes music so extraordinary. history of opera. Of course we Nobody can define it, and because of that, we insist so much have to do new operas! The success of Madame Butterfly or on the rationalism of our The Marriage of Figaro thoughts, and craftsmanship, and shouldn't be used to reject any tradition. All this is done with a kind of adventure with a contemc comedic rationalism. Music is porary language. I want this to inexplicable, and I'm very glad be very clear. You know that I about that (hearty laughter). am an example of the responsibilities of musical theatre, and an STEENHUISEN: What is the political subtext? example of saying 'No' to this world of opera. live never written for the applause - you know · this. STEENHUISEN: Yes. KAGEL: At the same time, I'm regarding, as an historian and cultural geologist, what happens with opera and that repertoire. I'm.regarding this and asking why this mixture of conservatism, pragmatism, and very poor instinct for adventure that is part of this world of opera? This, for a certain nucleus of people, can be very provocative. STEENHUISEN: Are you also mocking convention? KAGEL: I'm composing. I'm breaking conventions, it's true, and I'm using this as dialectical material for my compositions. STEENHUISEN: But there is also a certain amount of absurdity in what is going on. KAGEL: Absolutely. The world in which we live is absurd, from the beginning to the WWW.THEWHOLENOTE .COM KAGEL: Practically all of our actions have political implication. It depends upon how strong our actions are. We are placed, by definition, in a political context. If you get on the subway without a ticket, you will be punished, because without paying, the city can't continue the subway. Money is part of political convention. All that we expect from the government is related to politics. We take it for granted, of course, but we, ourselves, are part of this political strategy. Nonpolitical actions don't exist. The only question is how conscious we are of the political substance of our actions. Related to music, I can tell you that· the most simple piece of music can become .a political manifesto if the political conte.xt of the country is against that music. In the time of apartheid in South Africa, I am sure that the Ninth Symphony of Beethoven wasn't played very often, because the words are revolutionary, and anti-apartheid. For example, in South America, in Argentina, I was astonished that the folk music (which is much more important in certain countries than the classical Western music), was suddenly forbidden because the words are against the present government. You see how political that nonpolitical music can become. '.fhis was a revelation for me, of the relativity of one message or another. Each message can be translated, and in the translation, perhaps you're not translating the words,. but the' meaning. These meanings can become flexible, and stress certain wontls over others, and you get a different message. At the same time, I'm not naive. I know that it's not possible to 'write a piece for piano and think this is political. In the sixties and seventies, I found it absurd that the political content of the piece w~s explained in the programme notes, while the piece just sounded like the Darmstadt school. This was not only naive and absurd, but treasonous to very serious ideas of political communication. In this way, intellectuals have, almost by defini- . tion, bad conscience, because · they know this is the tradition of ·the twentieth century, they know they are speaking about the proletariat, but they are not a part of the proletariat. They're trying to educate the workers, but the workers are in the factories . They make pieces that say that the system is bad, and there are crimes to humanity and the . world, but to write it about the people who don't listen to it, who hate it, is eminently absurd. It was an escape from reality, and has nothing to do with politics. I was against that, but wrote a piece like Der Tribun, which .is about a politician pre- . paring a SP.eech, using applause from a tape and march music that is impossible to march with because the rhythm changes all the time (Ten Marches to Miss the Victory). I prefer to write music instead of manifestos. I am only a composer, and I'm not preparing something that will be effective in the political field, but I am conscious that musical language and musical style are two different things . We have to work to develop a very fine grammar and semantics of musical language. This is a part of my work. 23

- Page 1: J ! ~~~::::.._..;.~~:....;...;.::.:

- Page 4 and 5: harmo US I muQ9l . "sheer radiance"

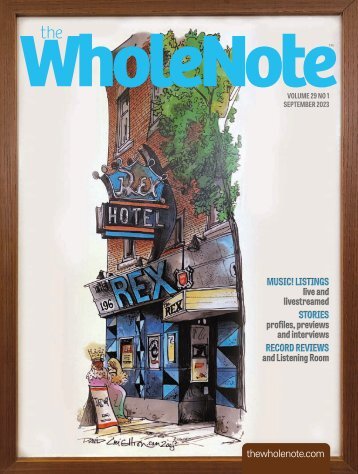

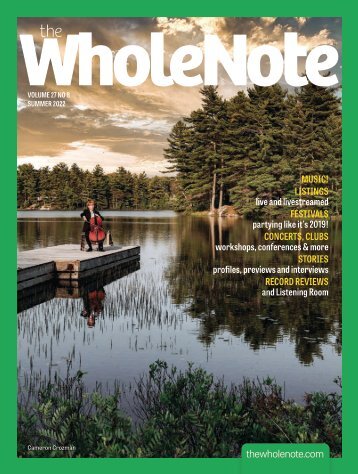

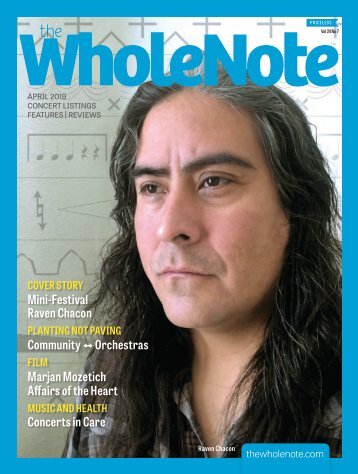

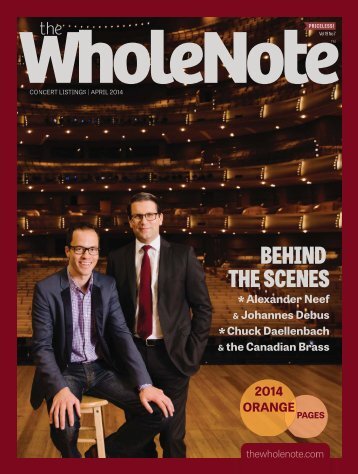

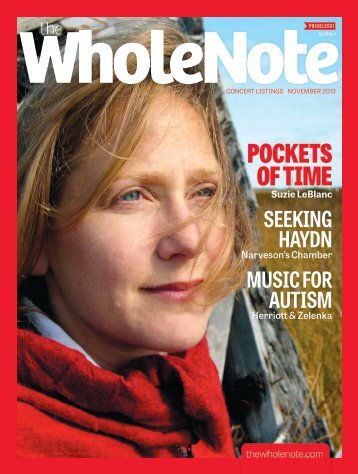

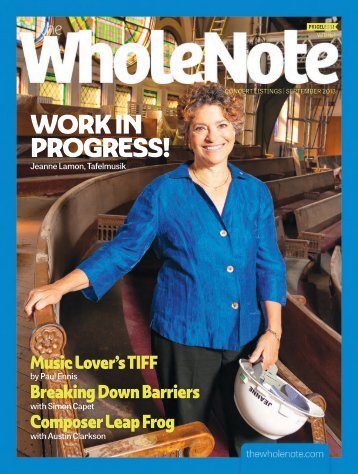

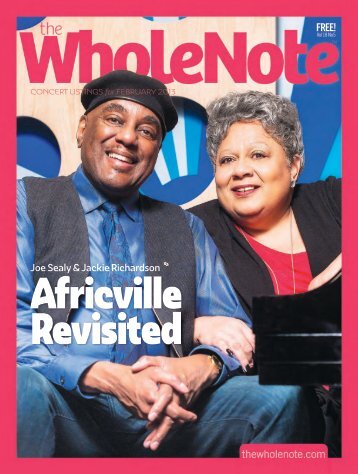

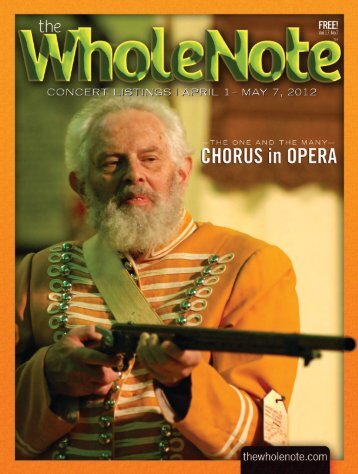

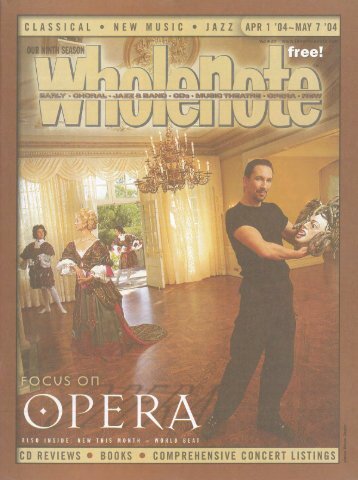

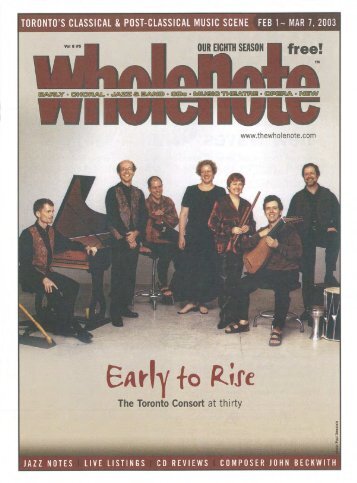

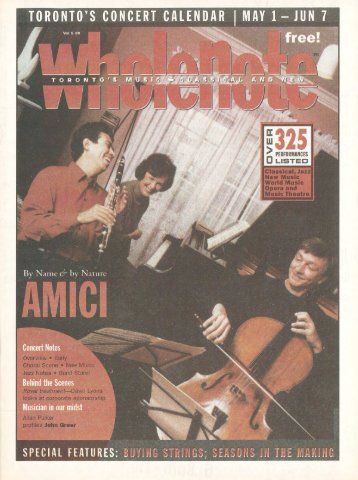

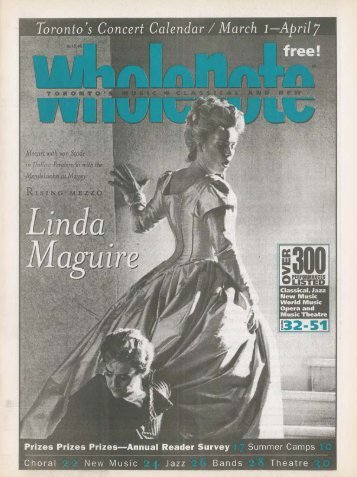

- Page 6 and 7: ' ~-.. ',. , , • L , ~ > ( ' COVE

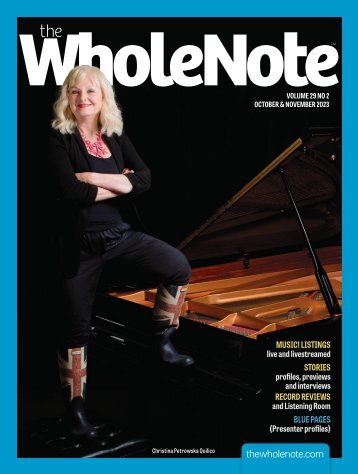

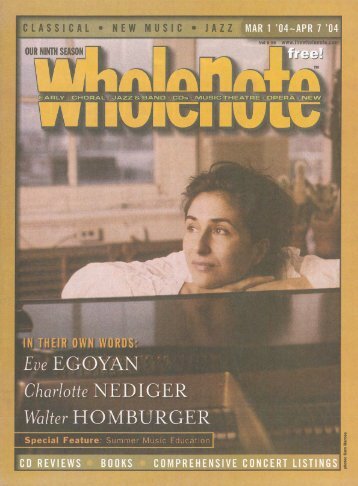

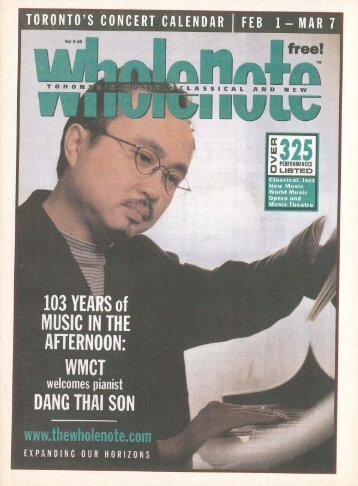

- Page 9 and 10: • • ? EVE~EGOYAN THE ART Of TOU

- Page 11 and 12: 2. I am working towards my CD relea

- Page 13 and 14: T.

- Page 15 and 16: my knowledge of technique and the p

- Page 17 and 18: Regular Peiformances: DON'T MISS TH

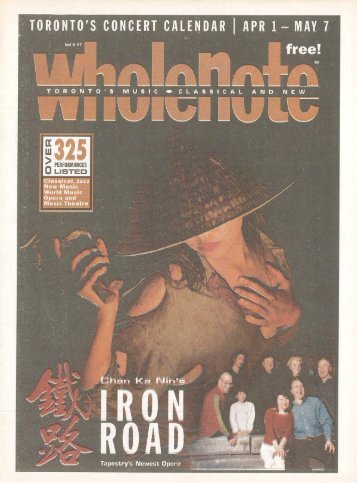

- Page 19 and 20: The story behind the ,composition o

- Page 21: K T 8 T • G I O R G I T N Ii M A

- Page 25 and 26: Page·aiitry & Processions Sunday,

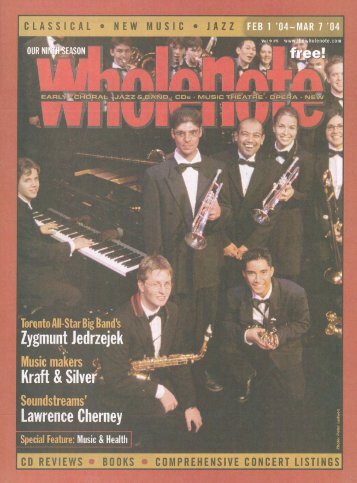

- Page 27 and 28: BAND STAND byMerlin Williams I thin

- Page 29 and 30: For an example of the kind of opera

- Page 31 and 32: Established 1981 OUR PRICE= MUSIC T

- Page 33 and 34: EDUCATION FRONT Focus on summer mus

- Page 35 and 36: Music ,h PoRT M1LF0Ro Phone: 914-76

- Page 37 and 38: Welcome to WholeNote's Live Listing

- Page 39 and 40: and gypsy music with classical pop

- Page 41 and 42: - 8:00: Royal Conservatory of Music

- Page 43 and 44: fox, clarinet/basset clarinet; Gill

- Page 45 and 46: - 7:00: VocalPoint Chamber Choir. C

- Page 47 and 48: - 3:00: Sinfonia Toronto. Young Peo

- Page 49 and 50: 5555. , (sr). (st). - 8:00

- Page 51 and 52: , 905-476-1093. . Saturday March

- Page 53 and 54: Tuesday March 30 7:30: University S

- Page 55 and 56: esidency with a focus on orchestral

- Page 57 and 58: ------------IJMtiili.,iiiit».·itW

- Page 59 and 60: of female models with vacuous facia

- Page 61 and 62: tality. Even though the Mazurka opu

- Page 63 and 64: The central focus of this disc i~ n

- Page 65 and 66: such a collection of "fusion-influe

- Page 67 and 68: RECENT RELEASES FROM BLUE NOTE CASS

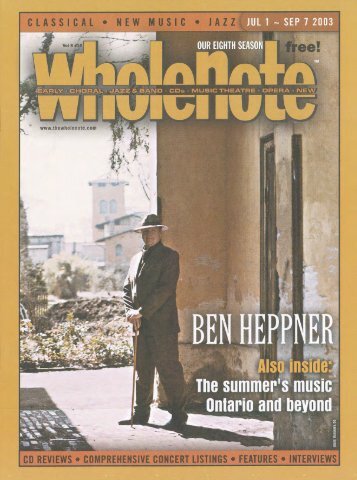

- Page 69 and 70: BEN HEPPNER - ldeale Songs of Paolo

- Page 72:

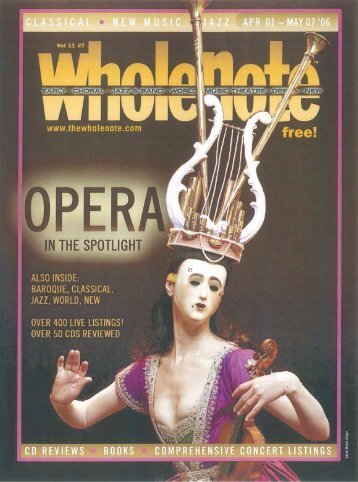

Apr 22(s), 24, 25(m), 27, 29, May 1

Inappropriate

Loading...

Mail this publication

Loading...

Embed

Loading...